The Valley of the Kings

About The Valley of the Kings

About

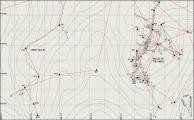

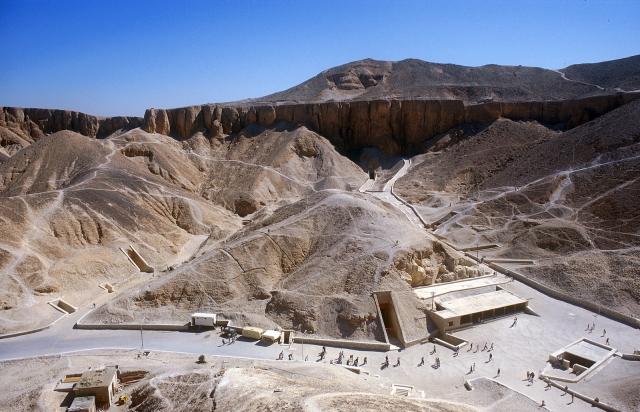

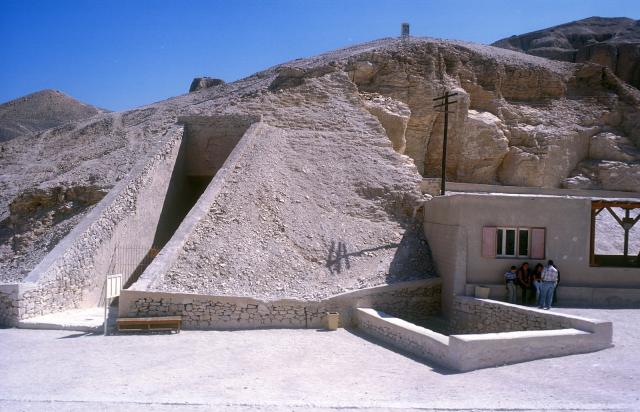

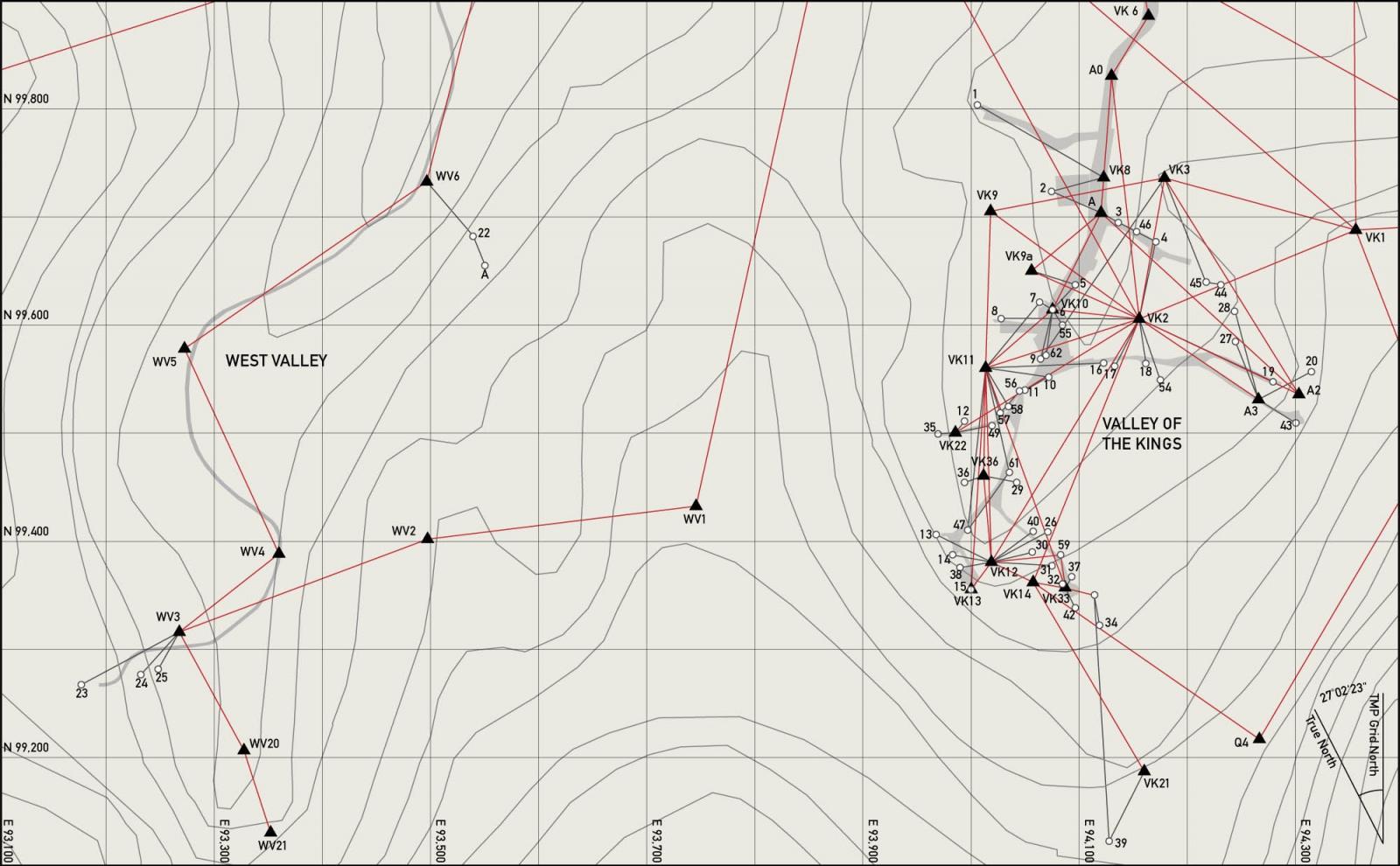

On the West Bank of the Nile across from modern Luxor, cut into the Theban Hills, lies the Valley of the Kings (KV). Chosen as the burial-place for most of Egypt’s New Kingdom rulers, it was selected for several reasons. It lies only a kilometer or so west of the temples and villages of the Theban people, it is a small valley surrounded by steep cliffs and is easily guarded, the bedrock in which it was cut by torrential rains millions of years ago is limestone of generally good quality, and towering above it is a mountain known today as the Qurn (meaning “the horn” in Arabic). The shape of the Qurn may have reminded the Egyptians of a pyramid, a shape associated with the sun god, Re, and long associated with royal burials.

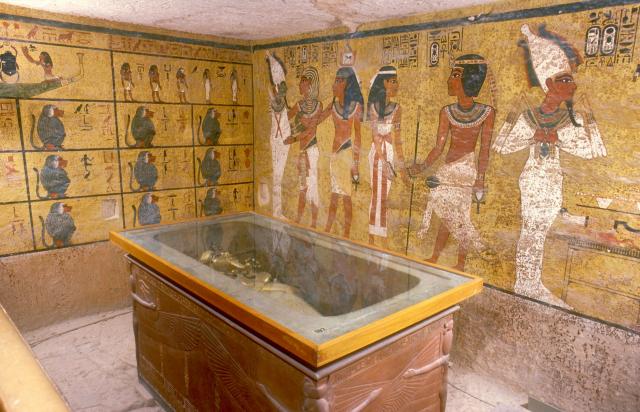

There are 64* numbered royal and private tombs in KV, ranging from small, pit tombs (KV 54) to huge labyrinths with over 120 corridors and chambers (KV 5). A few tombs have been “discovered” only in the past hundred years or so (KV 62: Tutankhamen; KV 46: Yuya and Thuya; KV 36: Maiherperi; KV 5: Sons of Rameses II ), but most had been opened - and plundered - long ago, some in antiquity, shortly after they were first sealed, others in Graeco-Roman and Byzantine (Coptic) times. There also may still be more. Dr. Zahi Hawass and an Egyptian-led expedition recently made a discovery tentatively numbered KV 65 in the West Valley, and their work is ongoing.

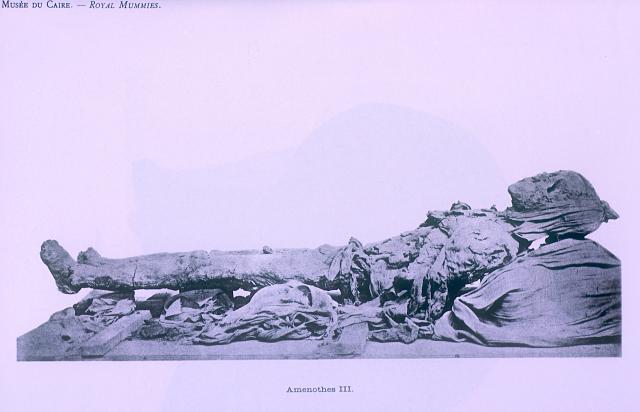

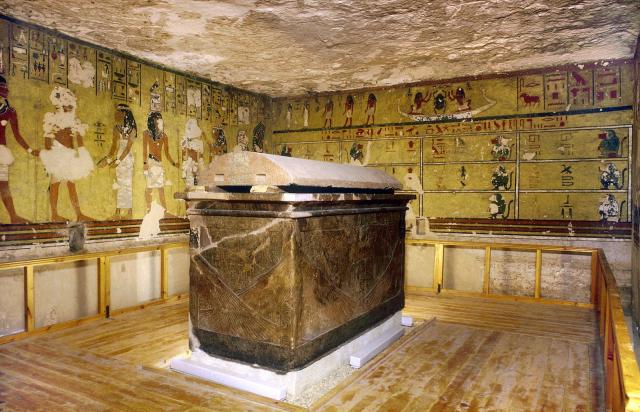

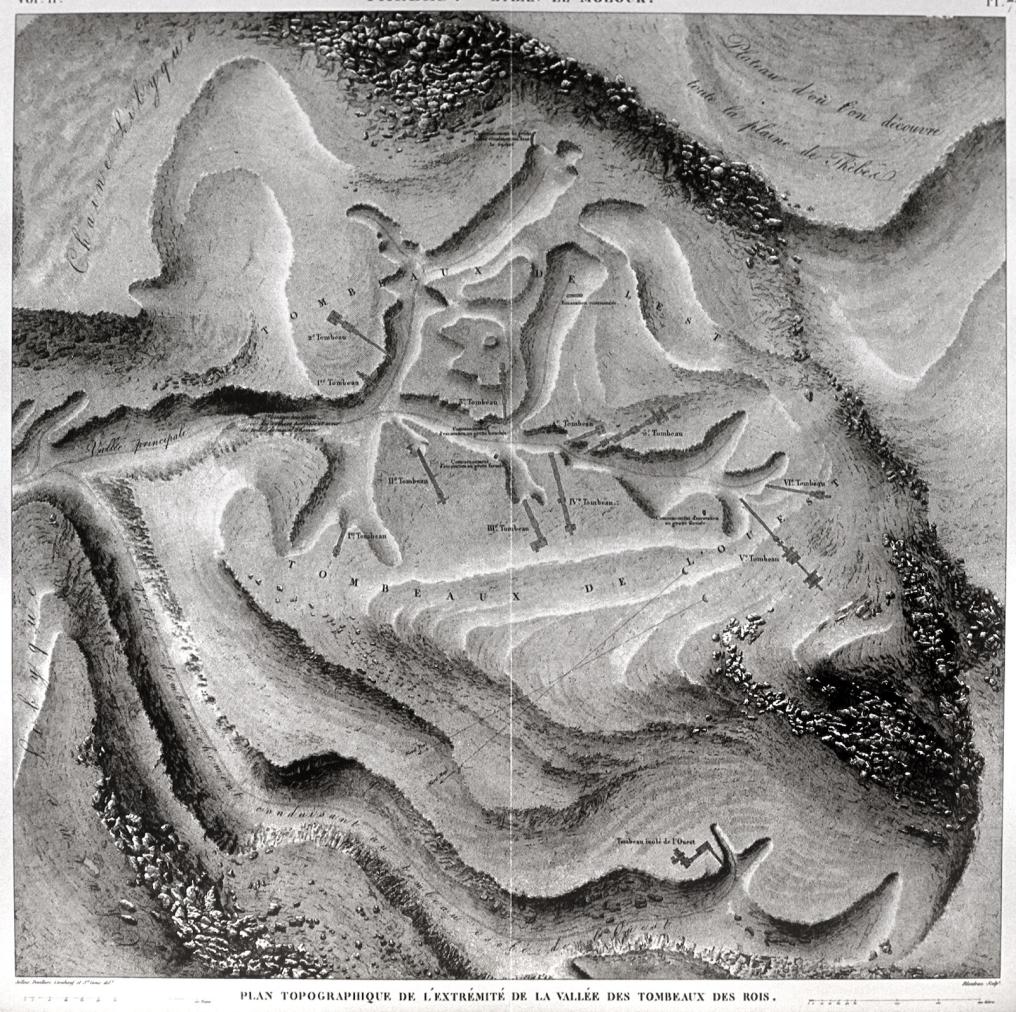

On this note, it is worth highlighting that there are effectively two Valleys of the Kings, the East and the West. The East Valley is the well-known one to which tourists flock and that contains the most tombs. The West Valley covers a much larger area and is the least explored. It has only two royal tombs, KV 22: Amenhotep III, and KV 23: Ay.

*KV 64 will be added to the website in future updates

Noteworthy features:

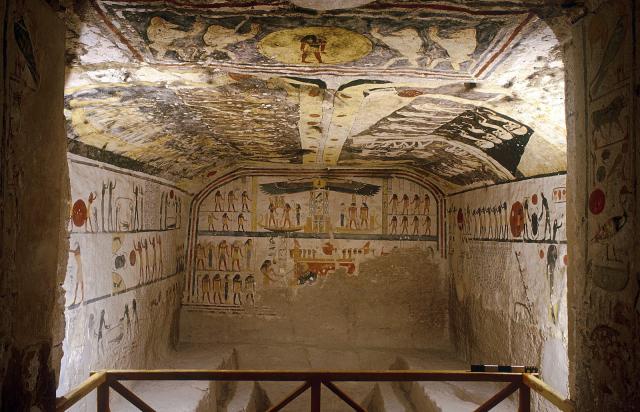

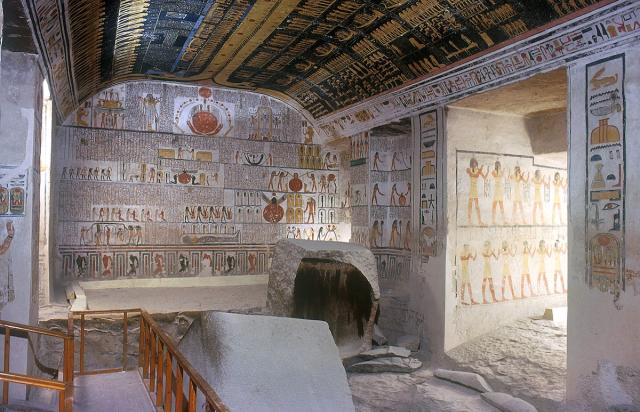

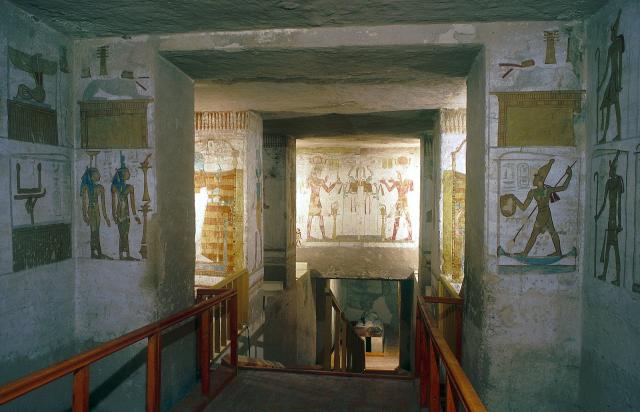

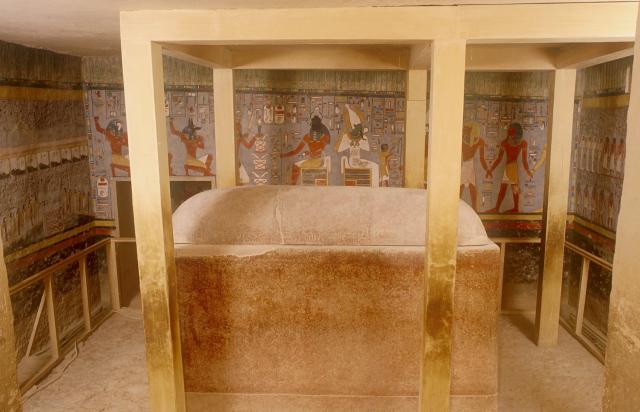

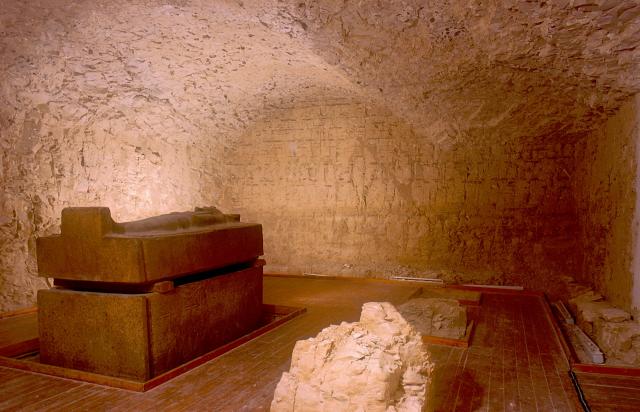

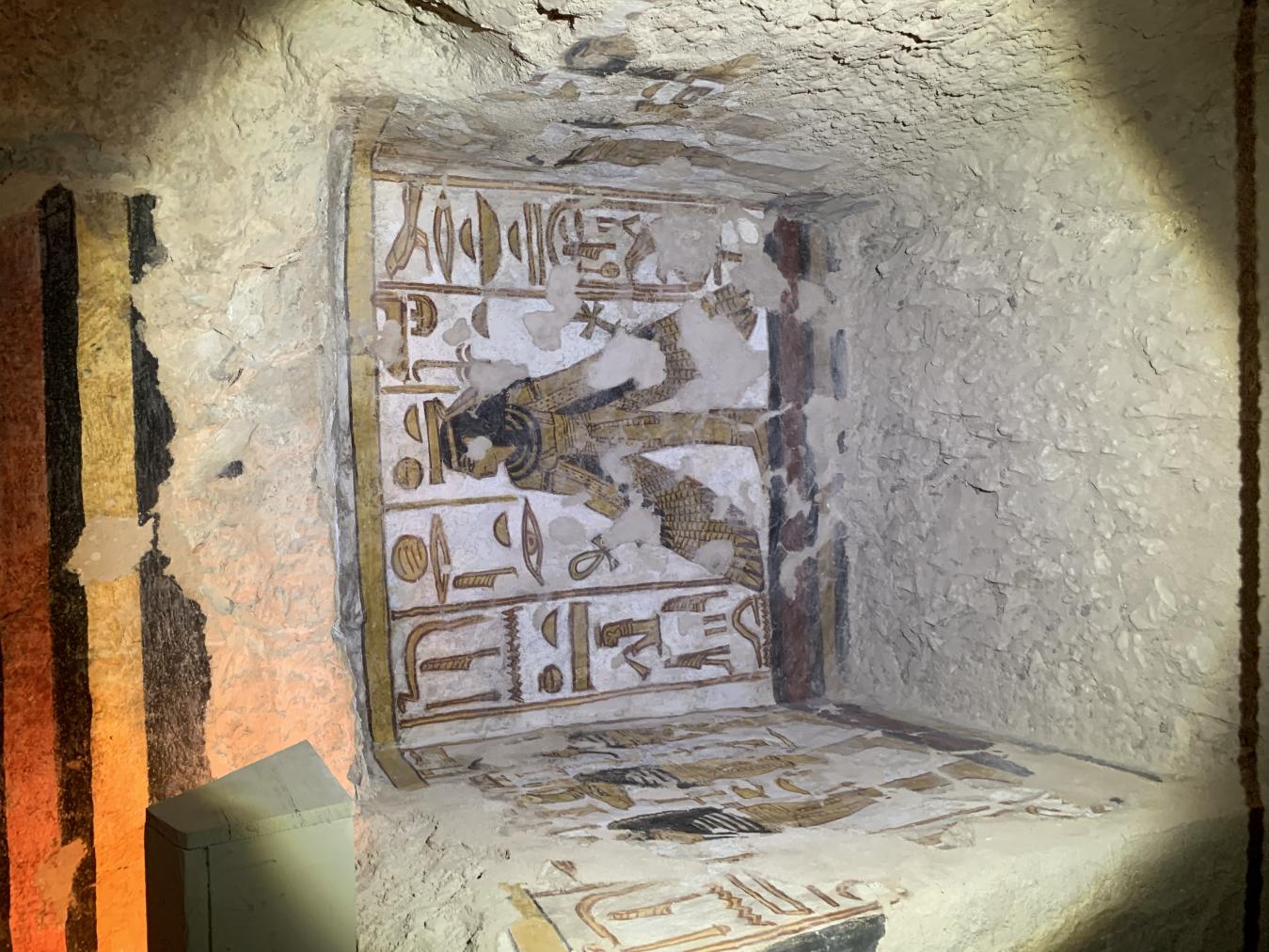

This is the principal burial site for the rulers of Egypt's New Kingdom. Its tombs contain unique examples of funerary decoration.

Site History

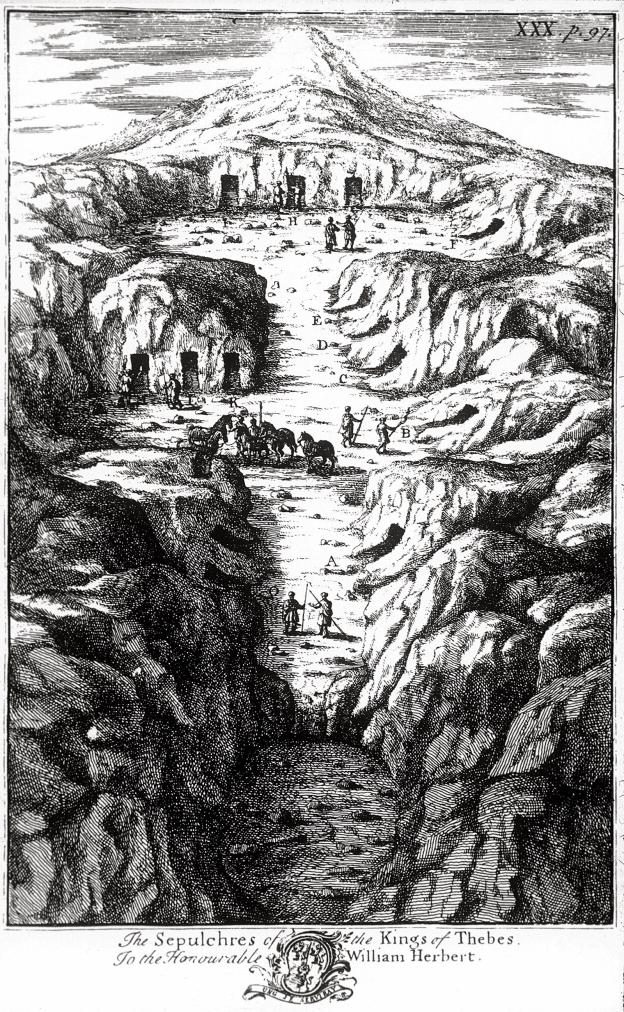

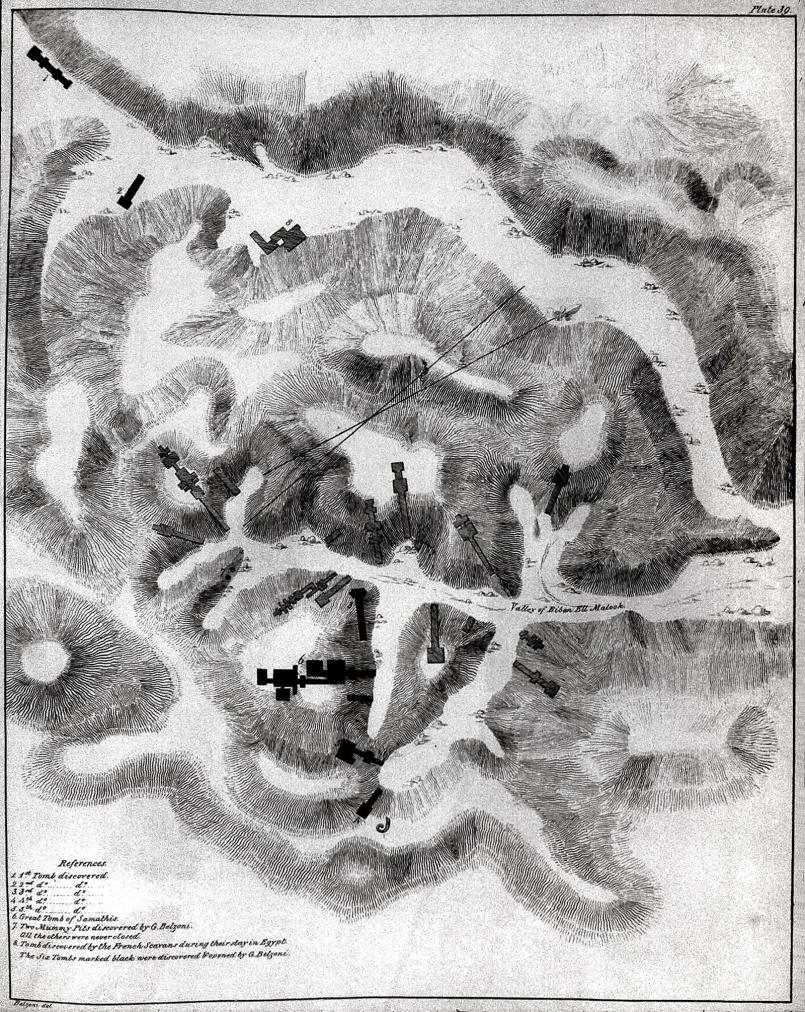

The earliest references we have to modern European visitors in the Valley of the Kings date to the eighteenth century. Early maps, such as that drawn by the scholars who accompanied Napoleon Bonaparte's 1799 expedition to Egypt, or those of Giovanni Belzoni (1818) and John Gardner Wilkinson a decade later, indicate that about twenty-five tombs were accessible since ancient times. Wilkinson was able to see twenty-one tombs and he numbered them in geographic order from the entrance of the Valley southward, then toward the east. Since then, tombs have been numbered in the order of their discovery, KV 64, an unnamed tomb containing the burial of a Chantress (singer) of Amun, being the most recent.

Many people have dug in the Valley of the Kings. One of the first was Giovanni Belzoni, who in 1816-17 discovered eight tombs, the most spectacular being KV 17, the tomb of Sety I. In the late nineteenth century, Victor Loret uncovered sixteen tombs, including a cache of royal mummies in KV 35, the tomb of Amenhetep II. From 1902 on, Theodore M. Davis sponsored thirteen seasons of work during which thirty-five tombs were cleared or discovered. One of his excavators was Howard Carter. In 1907, Carter began working with Earl Carnarvon. In 1922, their work led to the discovery of Tutankhamen's intact burial (KV 62), the only virtually intact royal tomb ever found in the Valley.

Apart from projects engaged in copying specific texts or documenting particular tombs, such as the work of Alexander Piankoff in the tomb of Rameses VI, published in 1954, the Polish epigraphic project in the tomb of Rameses III (KV 11) between 1959 and 1981, the work of Hartvig Altenmüller (KV 14) and Eric Hornung (KV 17, KV 22 and KV 35) there was relatively little archaeological activity in the Valley from 1922 (when the tomb of Tutankhamen was discovered) until the 1970s. Since the 1970s there was a resurgence of activity. In 1972, a project of the University of Minnesota, directed by Otto Schaden, began work in the West Valley in the tomb of Ay (KV 23).

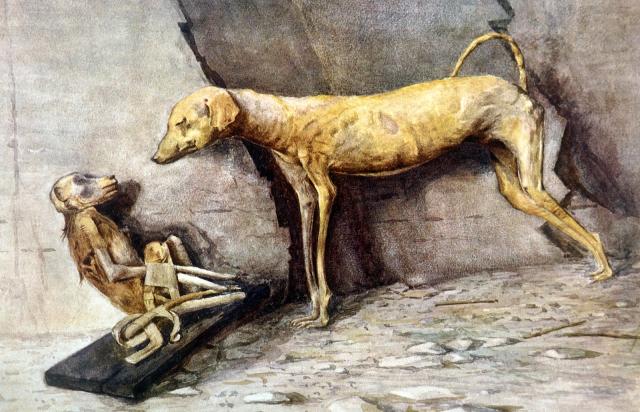

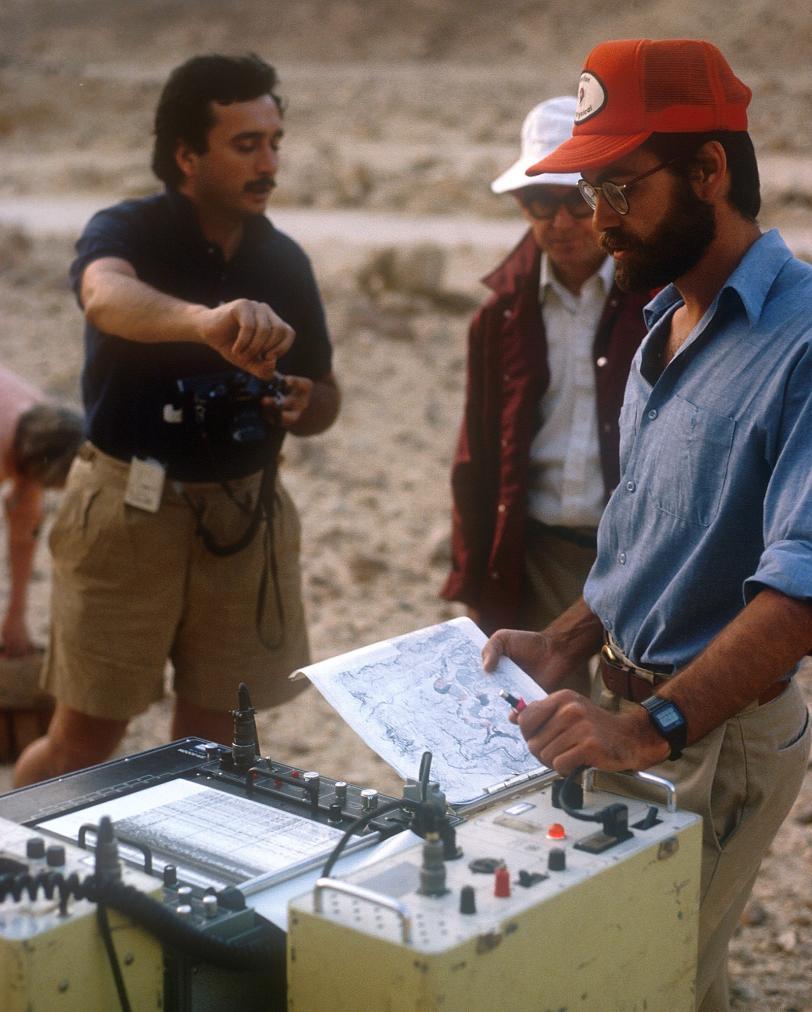

The Theban Mapping Project, under the direction of Kent Weeks, has worked in the Valley of the Kings since 1980. Its publications include the Atlas of the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the King: a Site Management Handbook in English and Arabic, and reports on the clearing of KV5, the tomb of the sons of Rameses II. A project led by John Romer for the Brooklyn Museum (1978-80) worked in the last royal tomb constructed in the Valley, that of Rameses XI (KV 4). Following documentation in the tomb of Tausert (KV 14) from 1983-1987, Hartwig Altenmüller of the University of Hamburg started excavating the tomb of Bay (KV 13), completing this task in 1994. In 1989, Donald Ryan of Pacific Lutheran University began a re-excavation and recording of several un-inscribed tombs, including KV 21, 27, 28, 44, 45, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, and 60. KV 39, thought by some to be the burial place of Amenhetep I, was excavated by John Rose beginning in 1989. In 1992 and 1993, Lyla Pinch Brock re-examined and carried out conservation in KV 55.

Nicholas Reeves and Geoffrey Martin examined the area between the tombs of Horemheb (KV 57) and Rameses VI (KV 9). The late Edwin Brock studied royal sarcophagi with particular emphasis on the remains in the tombs of Merenptah (KV 8) and Rameses VI (KV 9), where he reconstructed the inner Sarcophagus. Richard Wilkinson and Kent Weeks edited the Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings (2016) which contains over 30 essays on the development, decoration, symbolism, and history of the KV tombs. An expedition from Waseda University, Tokyo, under the direction of Jiro Kondo cleared, documented, and conserved the tomb of Amenhetep III in the West Valley (KV 22), and the area around it. Zahi Hawass has been clearing areas in both the East and West Valleys of the Kings. A Finnish-Swiss project has cleared and mapped the Village de Repos, a collection of workmen’s huts on the slopes of the Qurn.

There are several archaeological projects currently at work in the Valley of the Kings. Christian Leblanc is clearing and recording the tomb of Rameses II (KV 7) for the CNRS (National Scientific Research Center in France), while across the road, the Theban Mapping Project (TMP) is excavating, recording, and conserving KV 5 (the sons of Rameses II). The tomb of Amenmeses (KV 10) was excavated by the late Otto Schaden, who also discovered KV 63. This work continues under the direction of Salima Ikram. The Ramesses III (KV 11) Publication and Conservation Project, headed by Dr. Anke Weber, has been excavating, documenting, and conserving the tomb of Rameses III (KV 11). Elina Paulin-Grothe and Susanne Bickel direct a project of the Ägyptologische Seminar der Universität Basel, clearing and documenting tomb KV 31, and in the tombs of Rameses X (KV 18), Siptah (KV 47), and Tia’a (KV32), and the surrounding areas. Andreas Dorn has made a thorough study of the Workmen’s Hunts in the East Valley.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Conservation

Conservation History

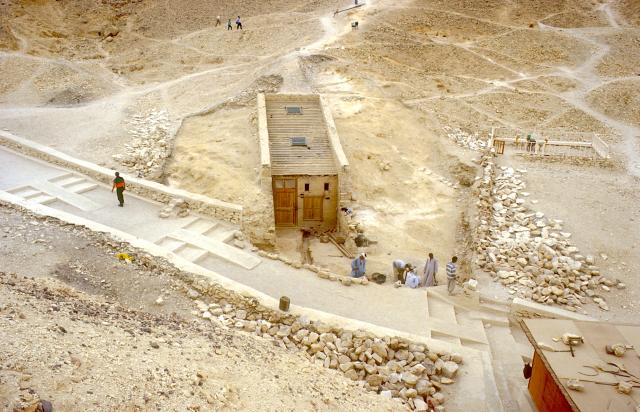

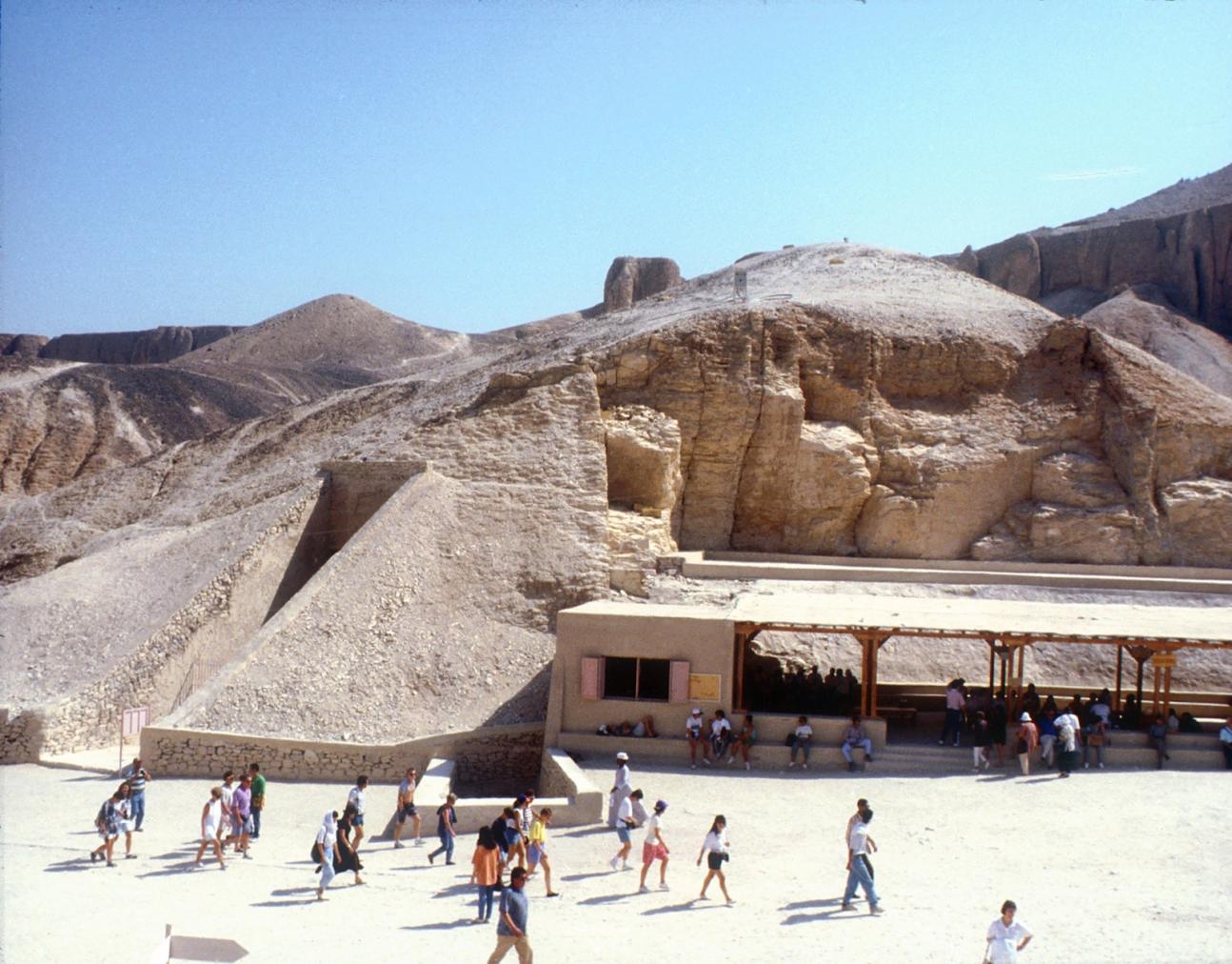

Much of the conservation measures enacted in the Valley of the Kings have consisted of removing earlier structures originally designed for touristic activities. This includes the removal of an old restaurant and bathroom from the center of the Valley, relocating souvenir kiosks from inside the Valley, and the demolishing of guard huts and donkey shelters built over and in the vicinity of tombs.

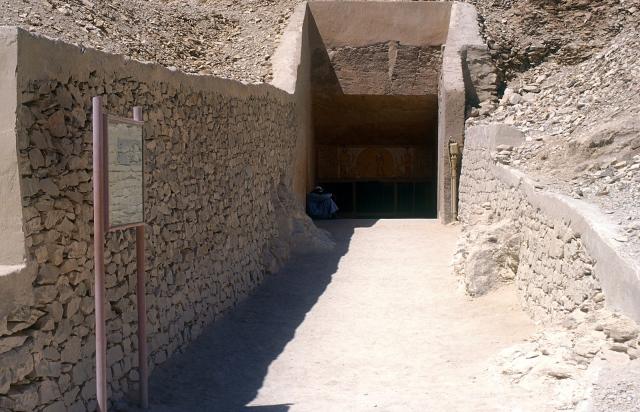

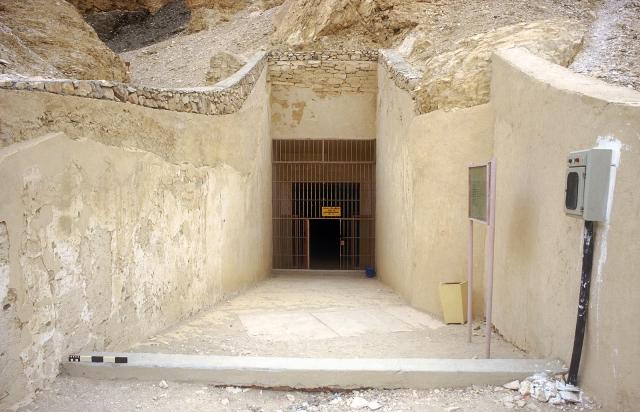

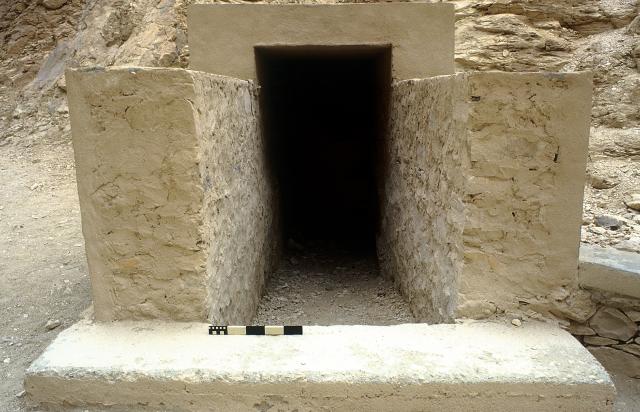

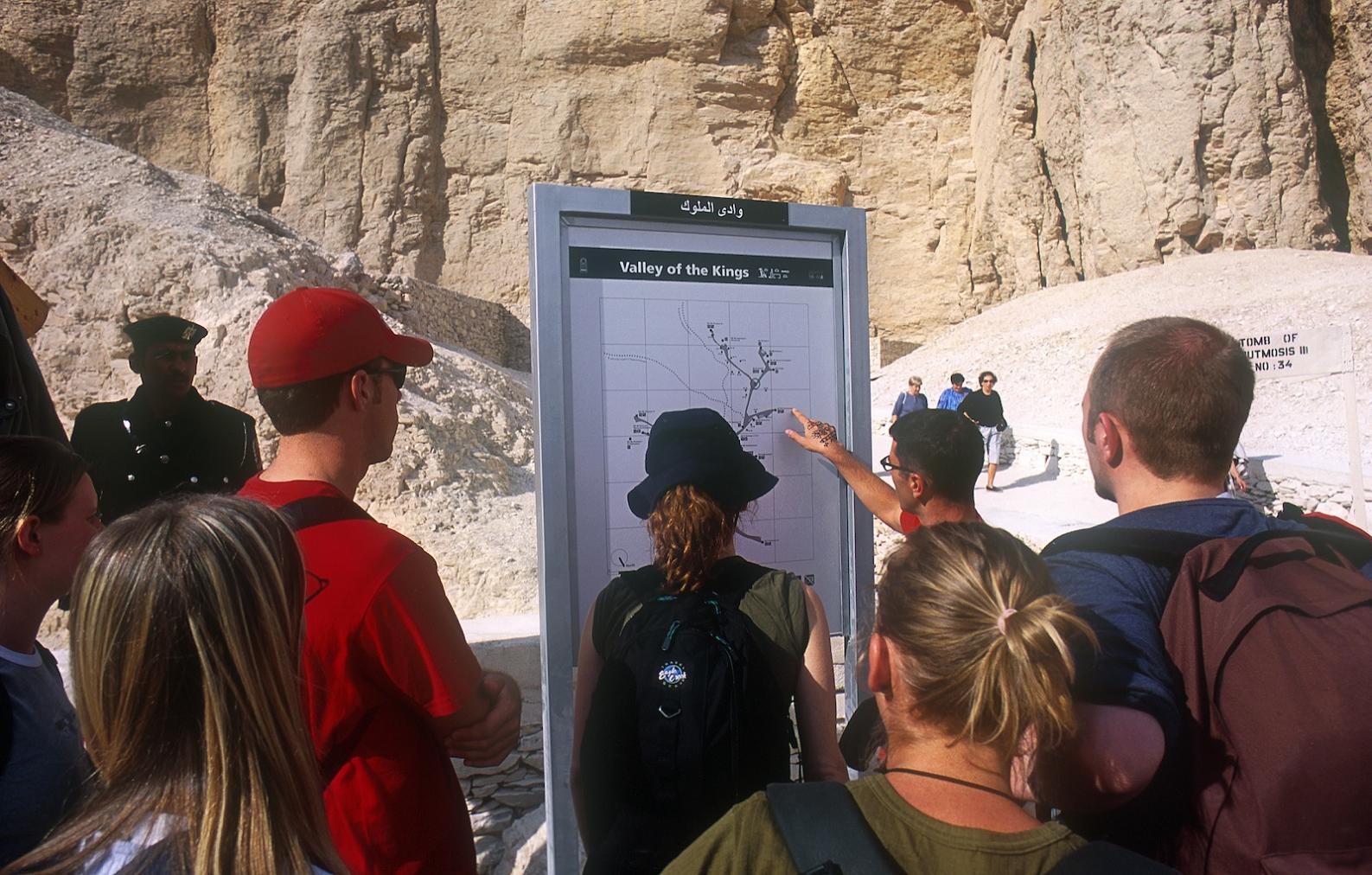

Other Steps have been taken to mitigate the negative affects of the visits of tourists. Cement steps and ramps ways created along paths, bordered by rubble retaining walls, to control the flow of tourists. An air circulation system was installed in KV 62 and plexiglass panels now protect the relief in many tombs from the hands of visitors. The Theban Mapping Project installed new informational signage to give tourists information about the tombs they visit before they enter.

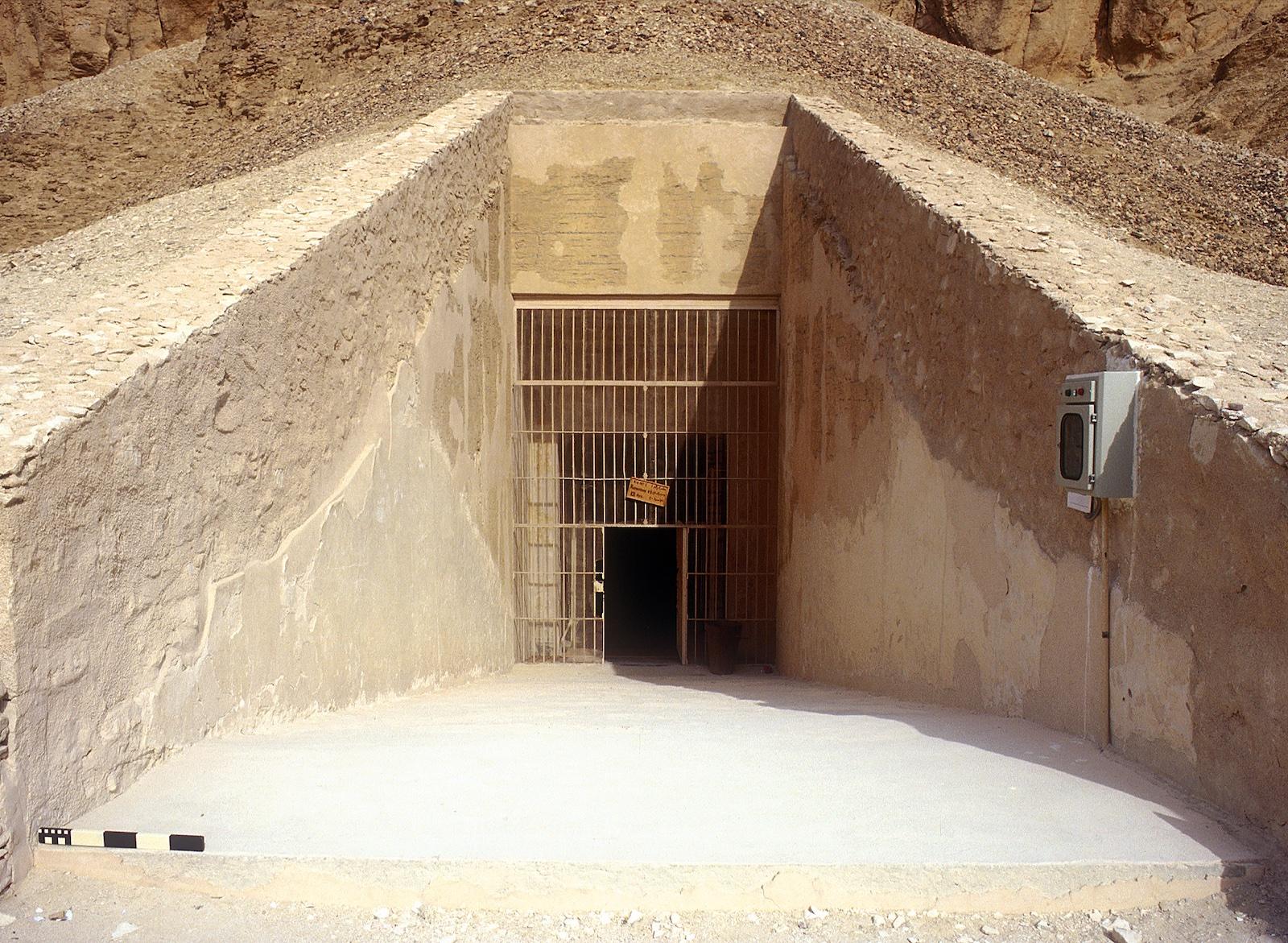

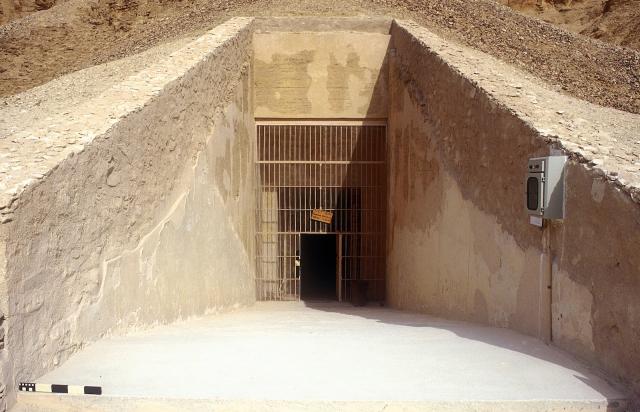

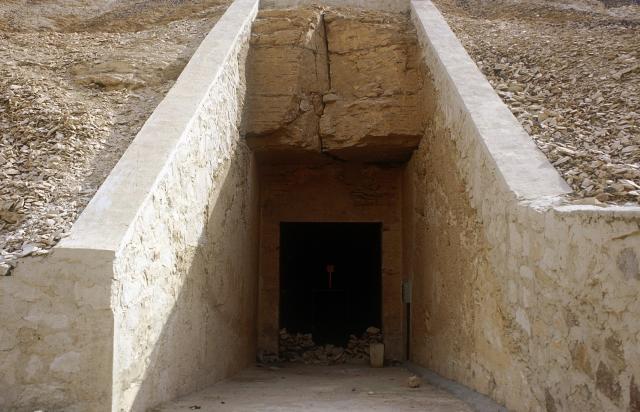

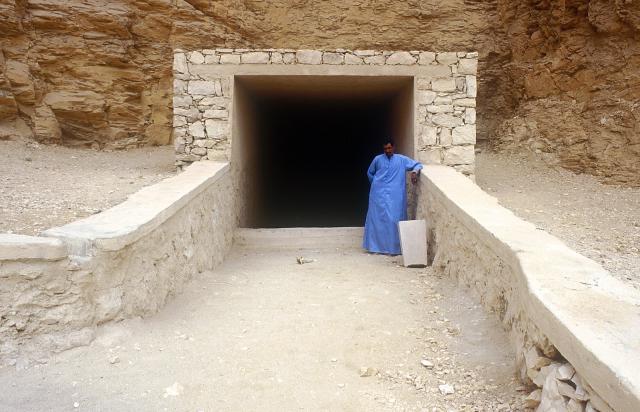

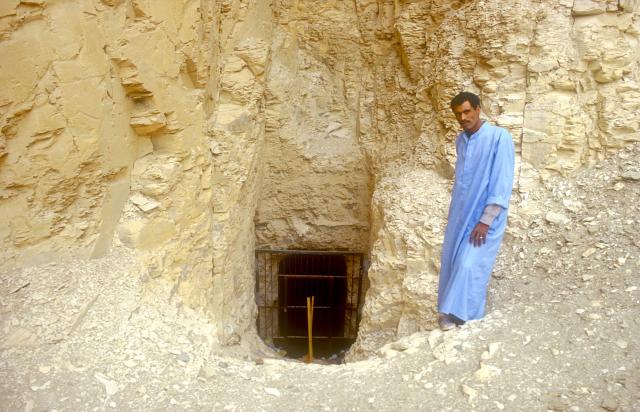

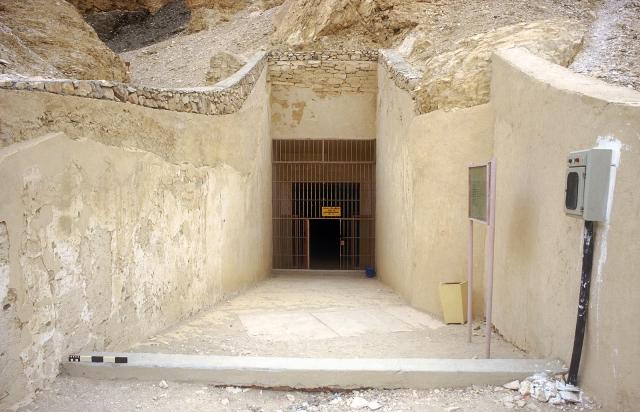

Flash flooding is a serious threat to the tombs and their decoration and has prompted the construction of shelters over entrances of tombs endangered by flood cascades (such as KV 13, KV 14 , KV 15, and KV 35). Flood deflection walls built around tomb entrances also protect from the effects of torrential rains.

Site Condition

Not all of the tombs in the Valley have been fully excavated. Accessible tombs are subject to physical stress from large numbers of visitors. Site maintenance is in need of revision. Trash collection is a problem. Open tombs are in danger of flooding. Internal rock movement is a danger to the structural stability of the tombs.

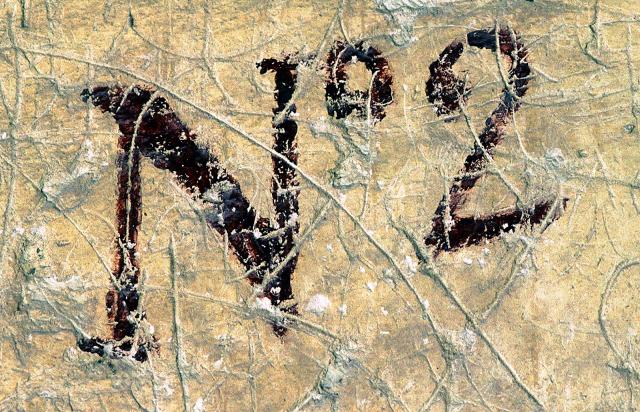

Hieroglyphs

Valley of the Kings

The Great Place

The Great Place

tA st aAt

Valley of the Kings.

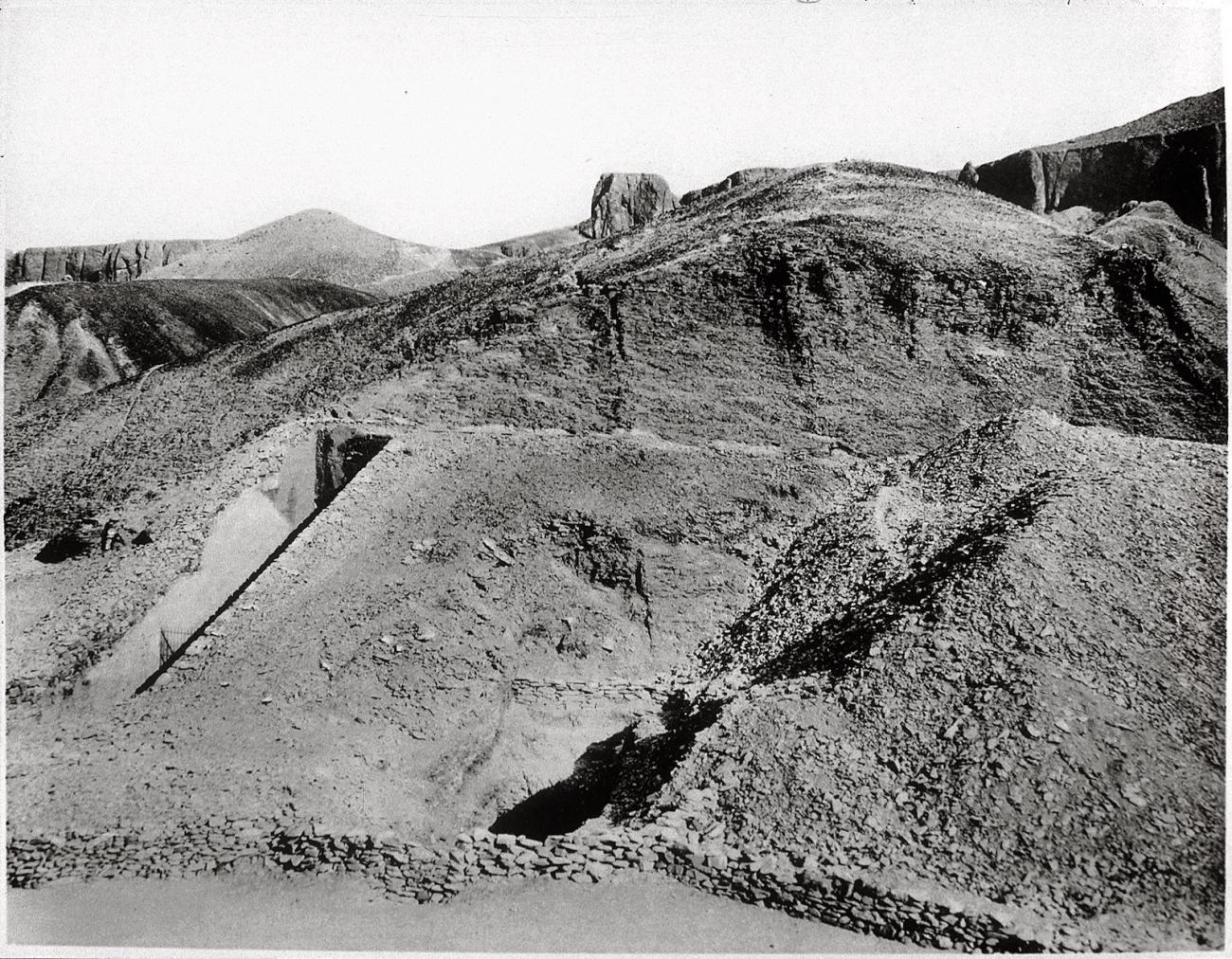

Hill above KV 11.

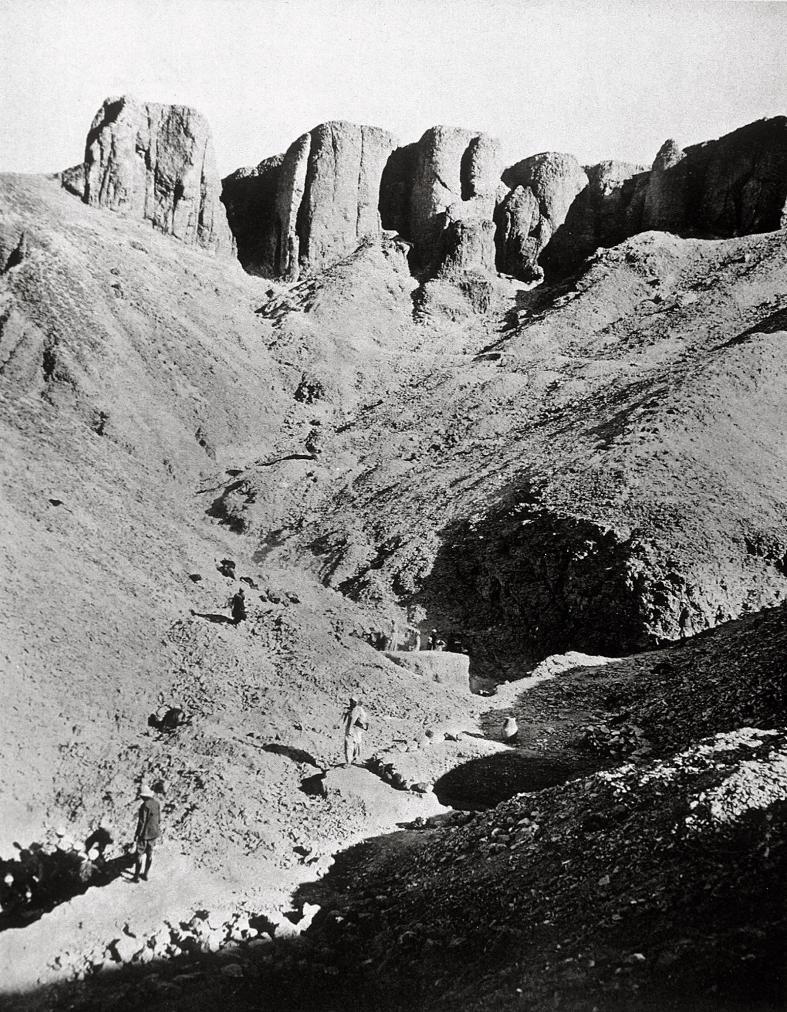

Panorama, view from hill above KV 9;looking toward hill above KV 11.

Valley of the Kings, cliff above KV 07, looking south; entrances to KV 62, KV 10, KV 09, KV 11, KV 08.

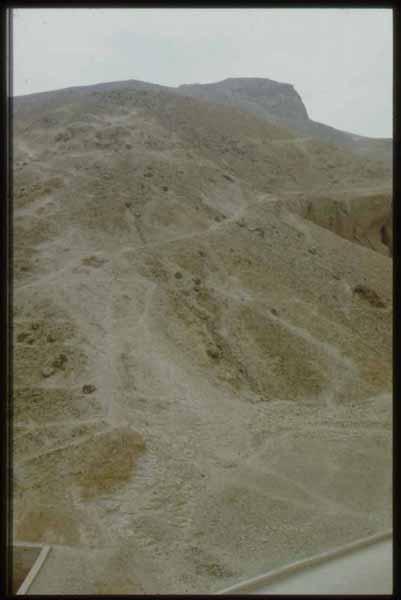

Valley of the Kings, panorama, looking southeast from cliffs above KV 07, with entrances to KV 62, KV 09, KV 10, KV 11, and KV 08.

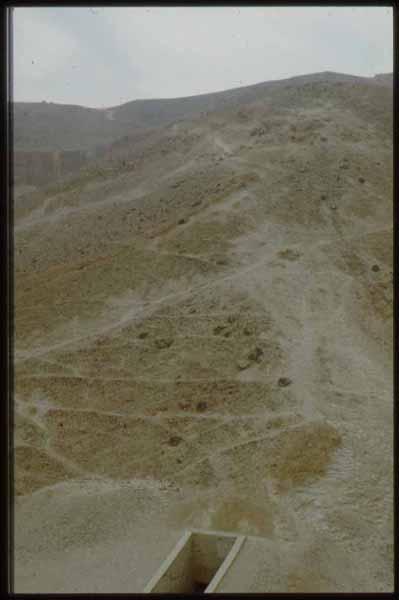

Valley of the kings, panorama, looking east from cliff above KV 07, showing entrances to KV 06, KV 07, KV 55, KV 18, KV 17, KV 16, KV 62, KV 10, KV 09, KV 11 and tourist shelter.

Path between KV 47 and KV 11.

Old rest house, KV 18, KV 17, KV 16, KV 55, KV 62, KV 9, KV 10 and KV 11.

Articles

Tomb Builders

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Kings

Historical Development of Royal Cemeteries

Bibliography

Abitz, Friedrich, Pharao als Gott in den Unterweltsbücher des Neuen Reiches (=Orbis biblicus et orientalis, 146). Freiburg, 1995.

Abitz, Friedrich. Die Entwicklung der Grabaschen in den Königsgräbern im Tal der Könige. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts: Abteilung Kairo. Wiesbaden. 45 (1989): 1-25.

Abitz, Friedrich. Die religiöse Bedeutung der sogenannten Grabräuberschächte in den ägyptischen Königsgräbern der 18. bis 20. Dynastie (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, 26). Wiesbaden, 1974.

Abitz, Friedrich. König und Gott: Die Götterszenen in den ägyptischen Königsgräbern von Thutmosis IV bis Ramses III (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, 40). Wiesbaden, 1984.

Abitz, Friedrich. Statuetten in Schreinen als Grabbeigaben in den ägyptischen Königsgräbern der 18. und 19. Dynastie (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, 35). Wiesbaden, 1979.

Afifi, A.R and Gen. Dash, Discovery of Intact Foundation Deposits in the Western Valley of the Valley of the Kings, in M.S. Pinarello et al. (eds.). Current Research in Egyptology. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Symposium, London and Philadelphia (2015). Pp. 1-10.

Ali, Mohamed Sherif. Hieratische Ritzinschriften aus Theban. Paläographie der Graffiti und Steinbruchinschriften. ( = Göttinger Orientforschungen, 34). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2002.

Altenmüller, Hartwig. Royal Tombs of the Nineteenth Dynasty. In: Richard H. Wilkinson and Kent R. Weeks (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. Pp. 200-217.

Amer, Amin A.M.A. The Scholar-Scribe Amenwahsu and his Family. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 127 (2000): 1-5.