The Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

About The Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

About

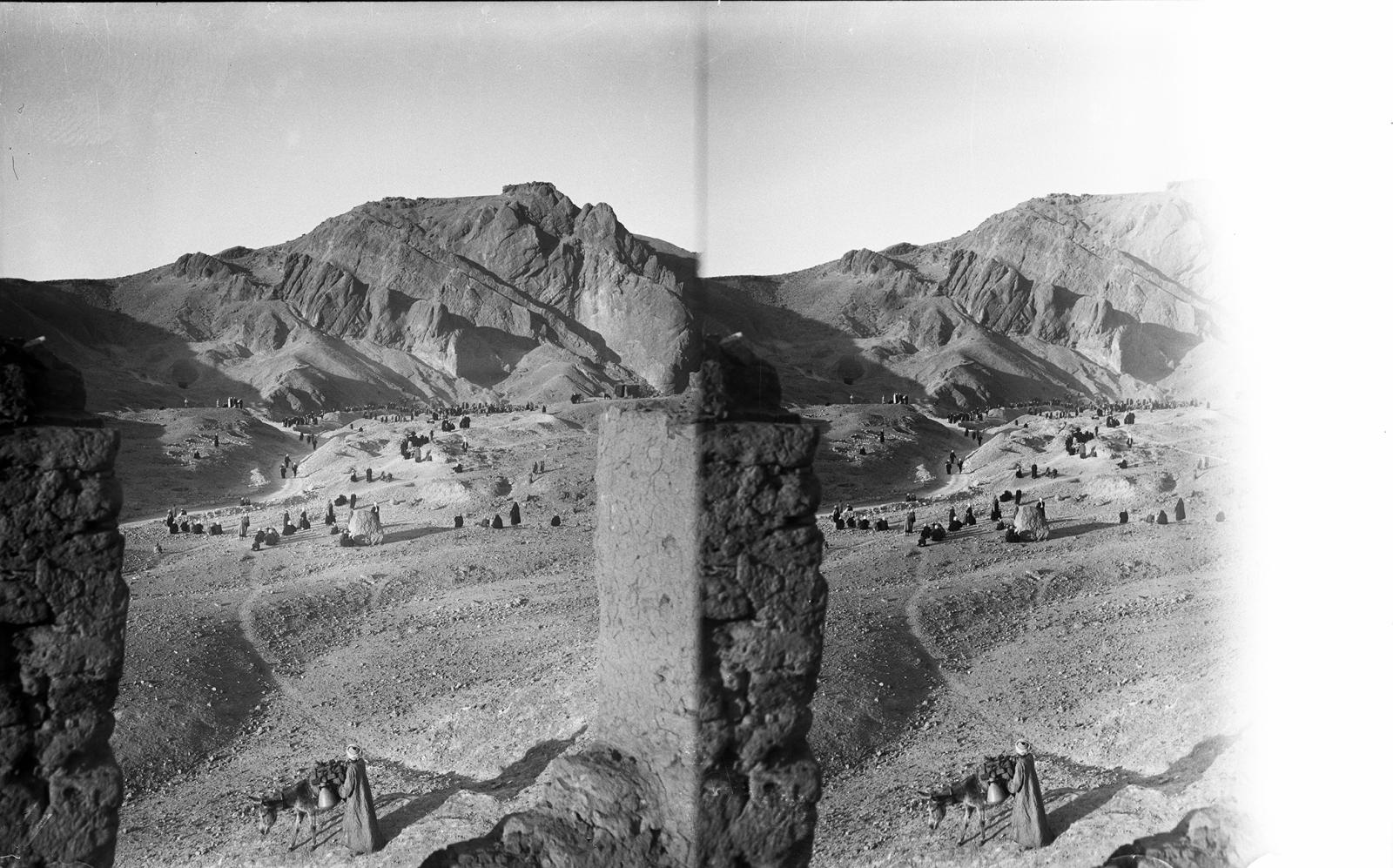

Approximately 1.5 km southwest of the Valley of the Kings, several wadis extend west from the edge of the low desert into and behind the Qurn, offering accessible but easily protected sites for burials. Here is where the tombs of many of Egypt’s New Kingdom royal family members lie. The most famous of these is the Valley of the Queens (QV). Commonly known in Arabic as Wadi Biban al-Malakat, QV has many other modern names, including Biban al Harim (“Gates of the Harim”) and Biban al Banat (“Gates of the Daughters”). Nearly all refer to female royalty, and it is their tombs for which QV is best known. However, the first people to be buried in QV were not queens but princes and princesses, sons and daughters of New Kingdom pharaohs. Indeed, the ancient name of the valley, ta set neferu, is a phrase that can mean both “The Place of Beauty” and “The Place of (Royal) Children”. The earliest burials in the QV date to the 18th Dynasty and were nearly all of royal offspring. It is only from the early 19th Dynasty onward that royal wives and mothers were also interred here. It is worth noting that a relatively small number of New Kingdom royal wives, sons, and daughters were buried in QV and nearby wadis in comparison to what is found in the historical record.

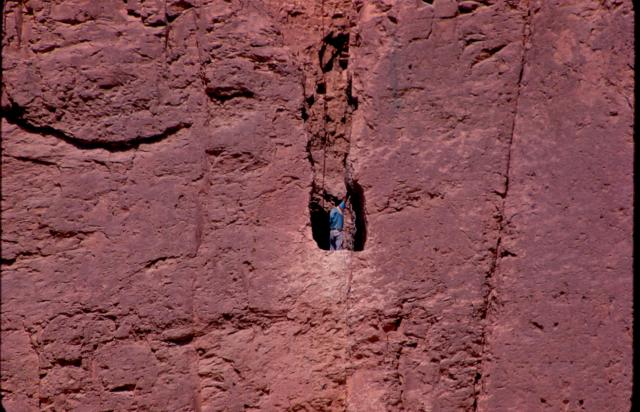

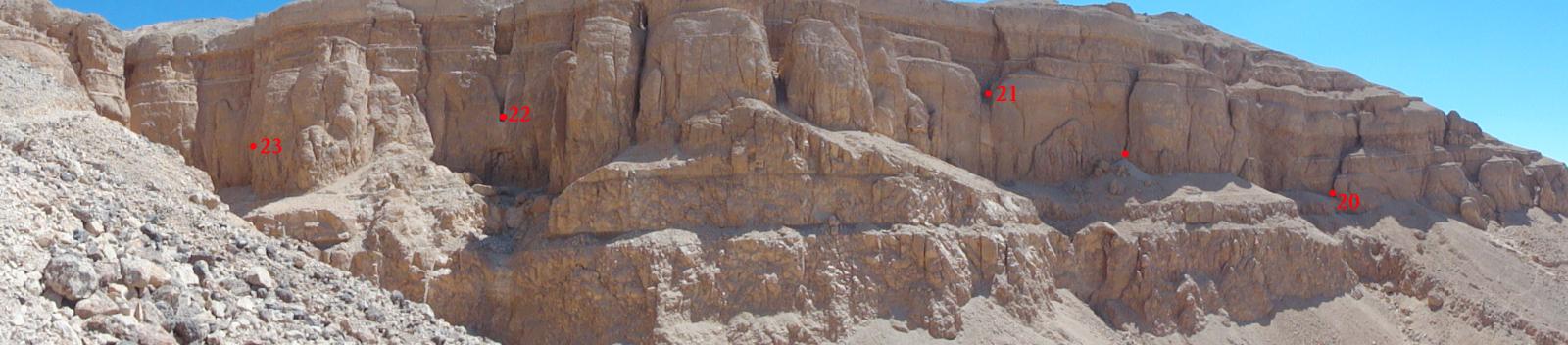

Lying close to the QV are 3 subsidiary wadis that were also used as burial sites for royal family members and elite officials. The tomb of Prince Ahmose (QV 88) was dug in the eponymous Valley of Prince Ahmose, together with that of an anonymous person (QV 98). Several Christian hermitages (called laurae) were later built here as well. The Valley of the Rope (Vallée du Cord, Wadi Habl), named by European visitors for a length of ancient rope hanging down a nearby cliff face, was the site chosen for several 18th Dynasty tombs (QV 92, QV 93, and QV 97). Lastly, the Valley of Three Pits (Vallée des Trois Puits) contains three shaft tombs (QV 89, QV 90, QV 91) and twelve smaller tombs of the Thutmosid Period (QV A through QV L).

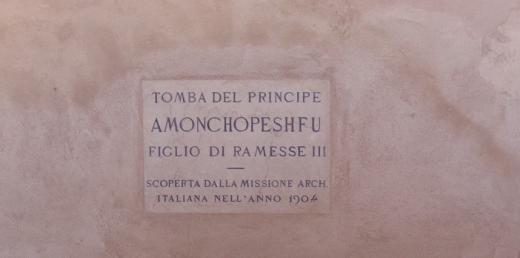

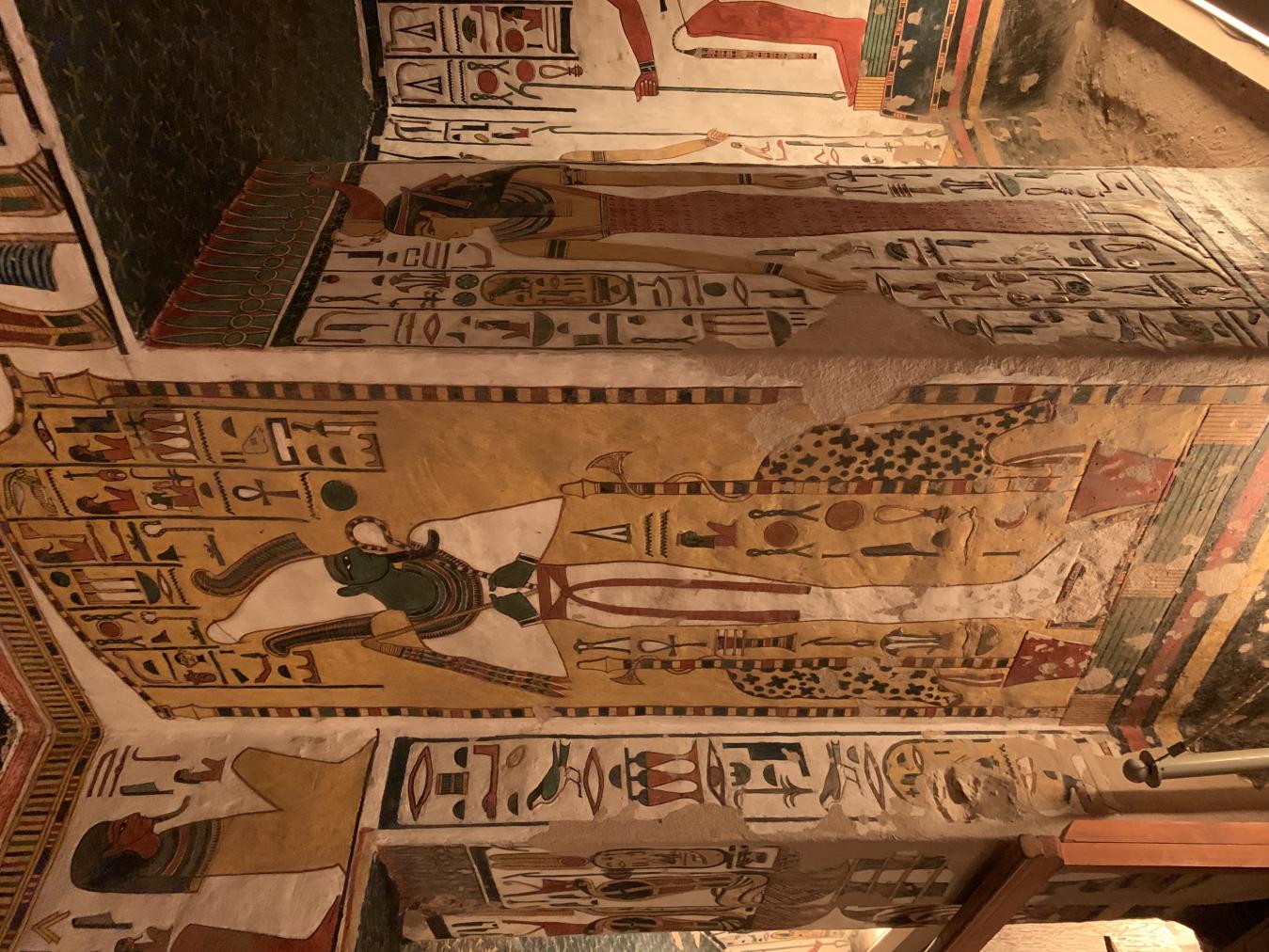

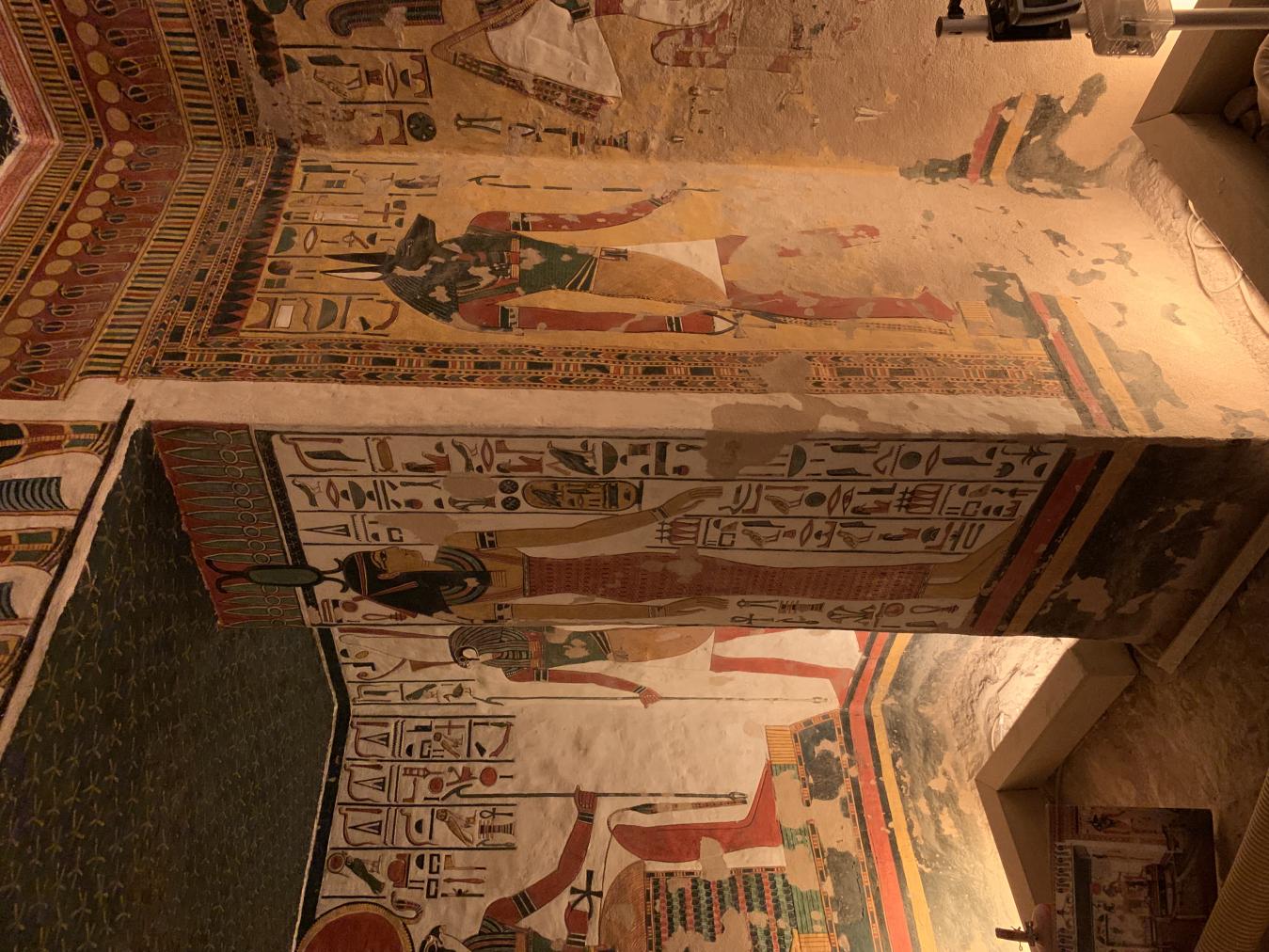

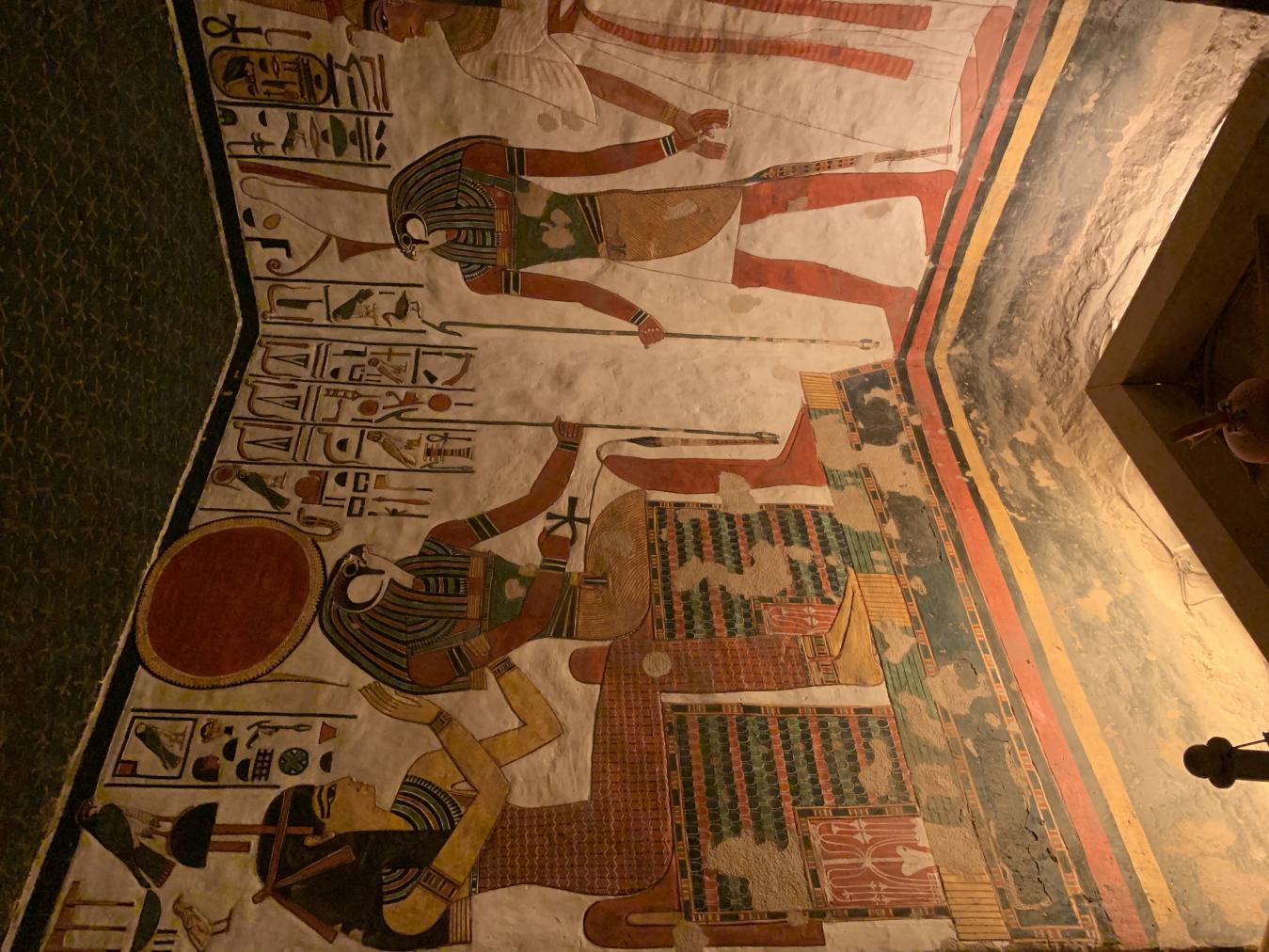

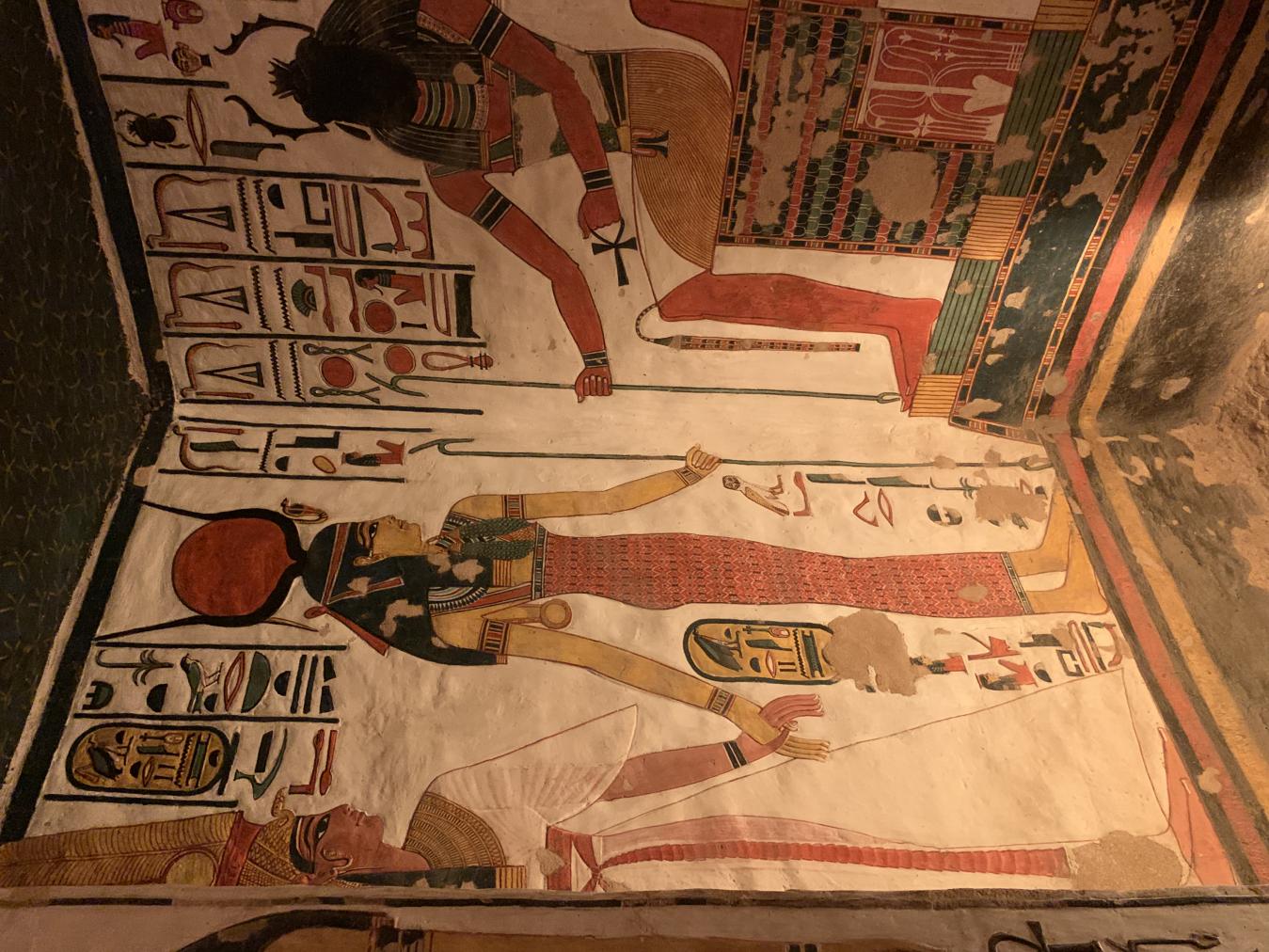

The numbering system now used in the QV and subsidiary wadis was developed by Ernesto Schiaparelli and Francesco Ballerini of the Turin Museum Italian Archaeological Expedition that excavated in the area from 1903-1905. The original plaques erected by Schiaparelli and Ballerini to commemorate a tomb's discovery can still be found at a number of the entrances, including QV 44, QV 52, and QV 55. One hundred and eleven tombs have been found in QV and subsidiary wadis thus far, but the names of only about 35% of their owners are known. The others are anonymous, some because their names were never written on the tombs’ walls, some because their names and inscribed grave goods were destroyed by floods or vandalism, and some because their tomb was reused and earlier texts erased. Furthermore, only 22% of the tombs in the QV and subsidiary wadis were decorated. The 18th Dynasty tombs were either left bare or plastered over and it is only from the 19th Dynasty onwards that the walls were decorated with images of the deceased offering to or adoring deities and scenes from various funerary books.

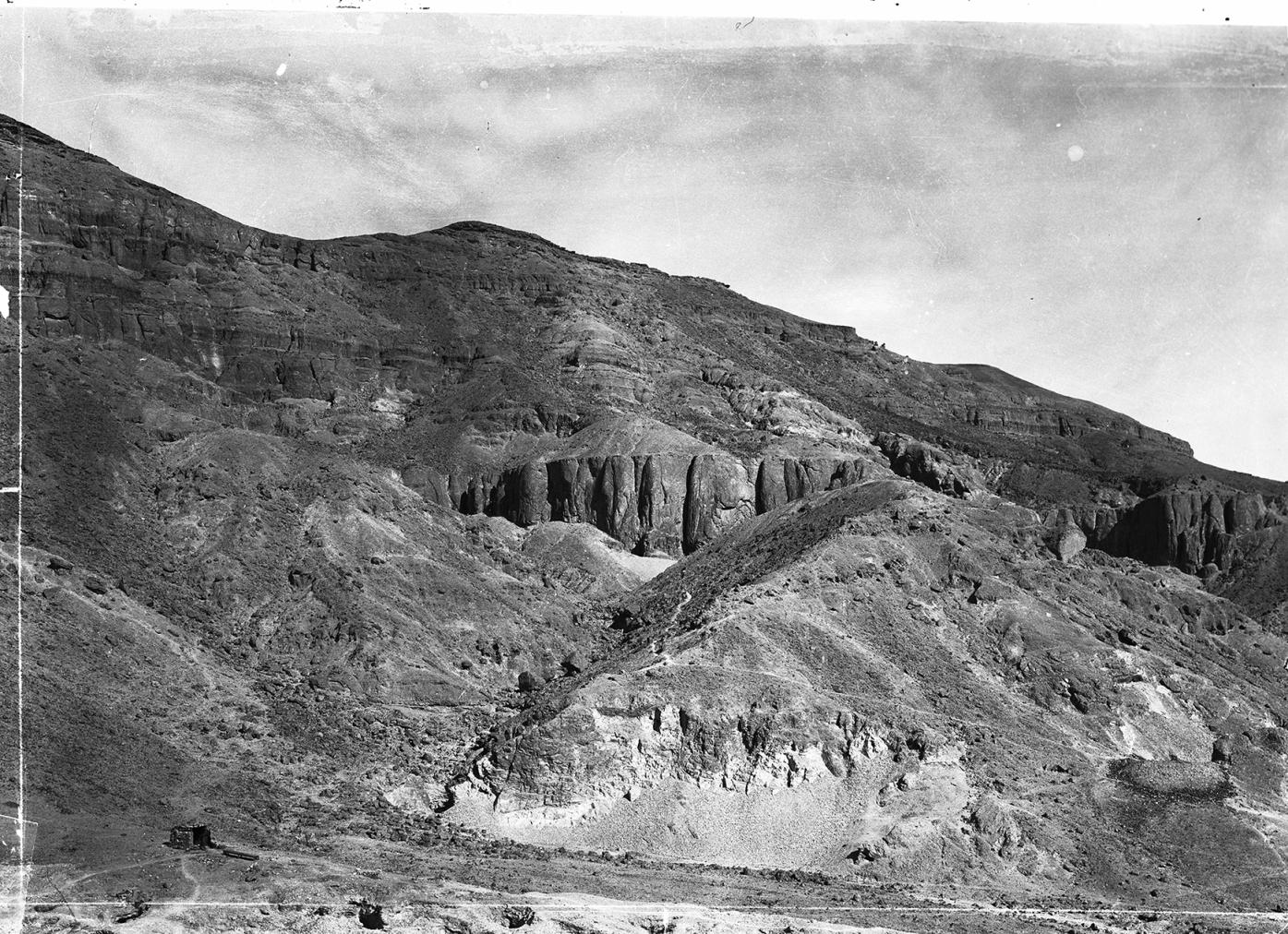

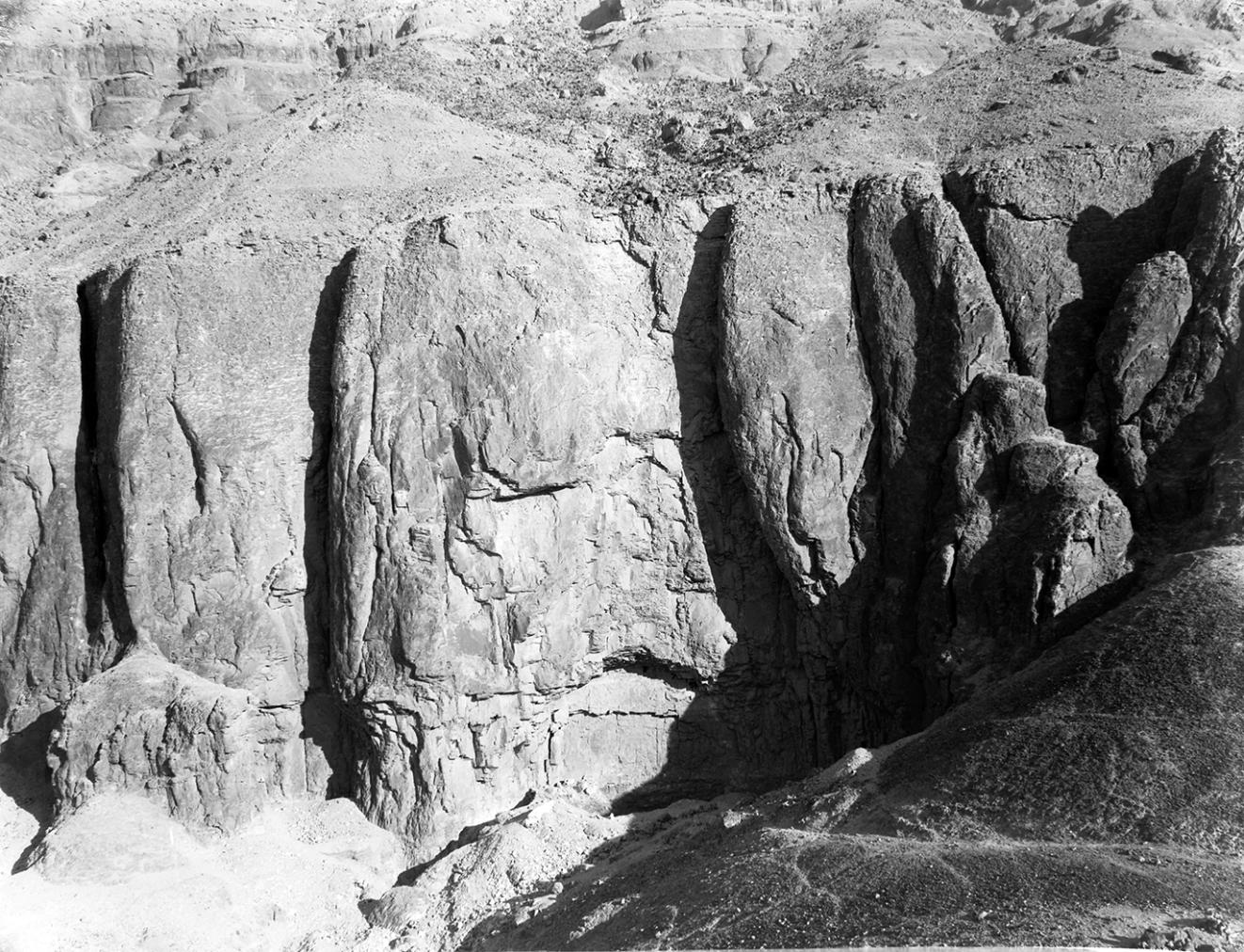

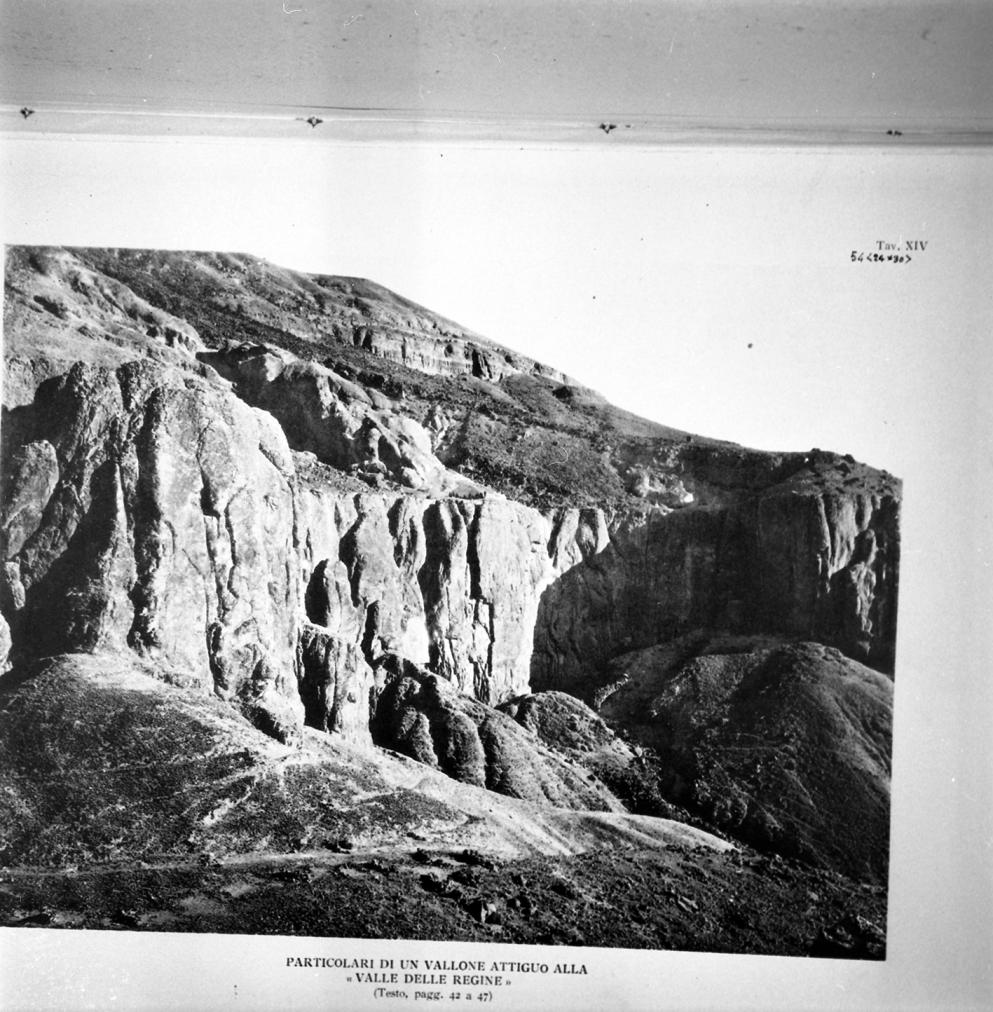

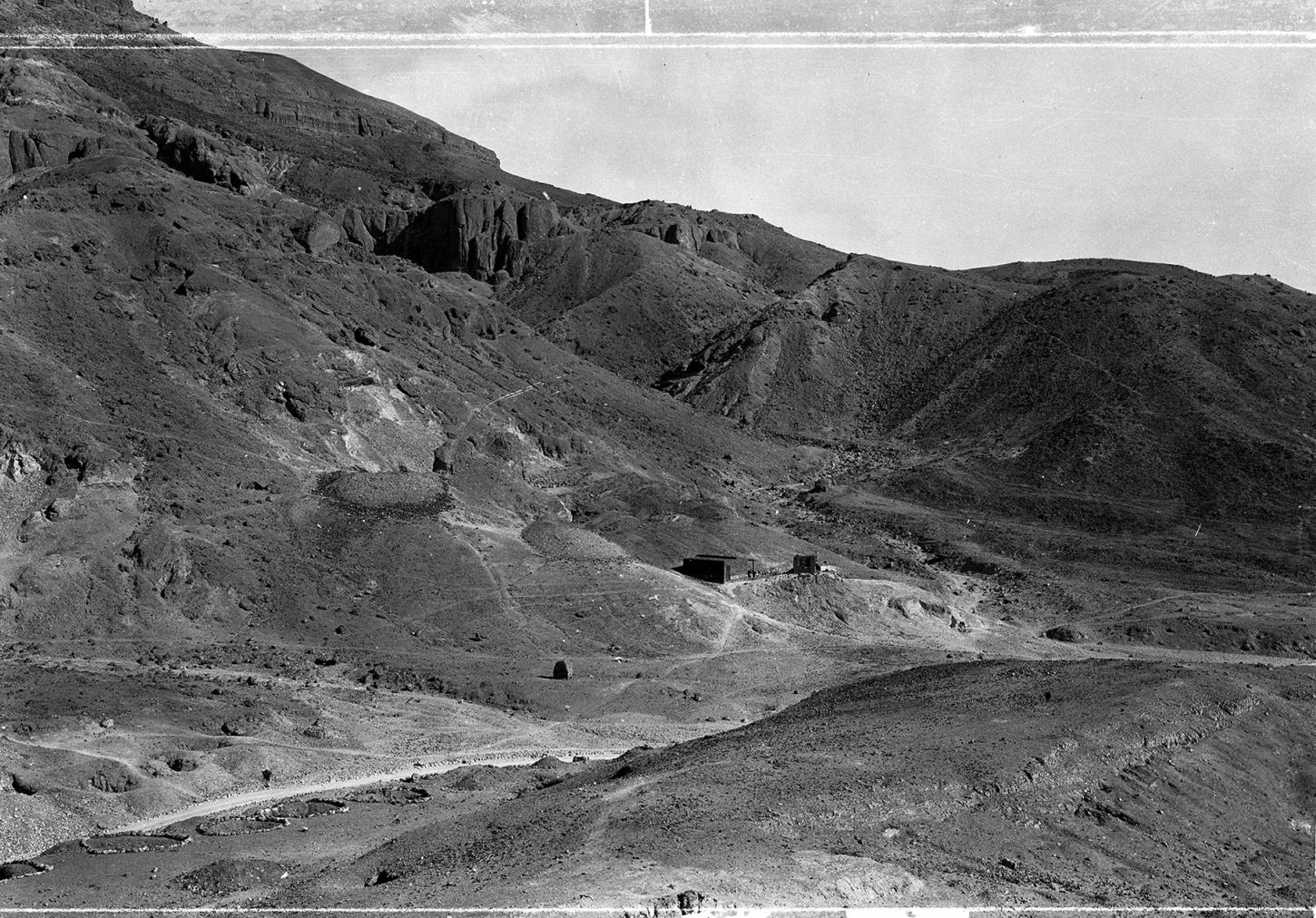

About two kilometers west of the QV, several large wadi systems cut deep into steep cliffs that define the back of the Qurn. These are collectively known as the Western Wadis. The area’s magnificent scenery has been remarked upon by nearly every archaeologist who has made the trek. Elizabeth Thomas wrote that “beauty alone … would make its exploration a pleasure.” Howard Carter observed that there was “no doubt” these wadis were cemeteries for 18th Dynasty royal wives and daughters, and that beauty and isolation were features that probably led ancient Egyptians to choose them, together with the more easily accessible Valley of the Queens. The Western Wadis refers to three wadi complexes in the area. Wadi Jabbanat el-Qurud includes several smaller wadis designated by Howard Carter as A, B, C, and D. Its name means ‘Cemetery of the Apes’, due to the fact that 19th century explorers found Late or Ptolemaic burials of over a hundred mummified baboons in Wadi D. Wadi A is the location of two cliff tombs, Wadi A-1 and Wadi A-2, as well as two pit tombs, Wadi A-3 and Wadi A-4. While Wadi A-2 is anonymous, Wadi A-1 was cut for Hatshepsut before her accession to the throne. Neferure, a daughter of Hatshepsut, may have been buried in a cliff tomb in Wadi C (Wadi C-1), although some have suggested it is the tomb of Merytra, principal wife of Thutmes III. A tomb in Wadi D (Wadi D-1), variously and confusingly also labelled HC 70, ET B, and D1 by various archaeologists, was dug for three Syrian princesses and minor queens of Thutmes III. Wadi al Gharbi, which includes Wadis E, F, and G, is the largest and most distant of the outliers. Some believe that the 20th Dynasty tomb of the High Priest and last pharaoh at Thebes, Herihor, may lie here undiscovered in Wadi F. However, this is unproved and considered doubtful by many. Lastly, a large complex of subterranean shaft tombs, WB 1, lie further west in Wadi al-Bariyah. In contrast to the hidden cliff tombs of Wadis A-D, these shaft tombs were excavated into a mound some 15m above the broad, flat flood-plain. The burial equipment discovered in and associated with these tombs indicate that they belonged to members of the royal court of Amenhetep III. Most recently, the joint mission between the New Kingdom Research Foundation and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities discovered a new royal tomb in Wadi C. This tomb most likely belonged to a great royal wife and several children of a Thutmoside king. The Western Wadis thus served as a precursor to the Valley of the Queens as the burial place of senior members of the royal family, namely Queens. The reason for the shift from the outlying wadis to the QV in the 19th Dynasty is unknown, but may be due to the easier accessibility of the latter.

Along a path leading from the QV to Dayr al-Madinah, a sanctuary was cut into the bedrock in the late 18th Dynasty in an area now known as the Valley of the Dolmen. It consists of seven chapels for Ptah and Meretseger, deities closely associated with the Theban necropolis and QV. Two man-made structures further along the path, termed "dolmen" and a "menhir" by early European travelers, were also sites of New Kingdom activity. The menhir was a small stone structure with several rooms that may have served as a place of shelter or worship for workmen. The dolmen was a small chamber built of stacked blocks that perhaps served similar functions. In the New Kingdom, security in QV and the surrounding area was maintained by small, stone guard huts along the ridge west of QV and nearby burial sites.

*The tombs marked with an asterisk (*) were not surveyed by the Theban Mapping Project and do not currently have plans.

Particular credit is given to the following publications produced by the Getty Conservation Institute through its Valley of the Queens Project:

Demas, Martha, and Neville Agnew, eds. 2012. Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: A Collaborative Project of the Getty Conservation Institute and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt. Vol. 1, Conservation and Management Planning. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/valley_queens

Demas, Martha, and Neville Agnew, eds. 2016. Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: A Collaborative Project of the Getty Conservation Institute and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt. Vol. 2, Assessment of 18th, 19th, and 20th Dynasty Tombs. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/valley_queens

Site History

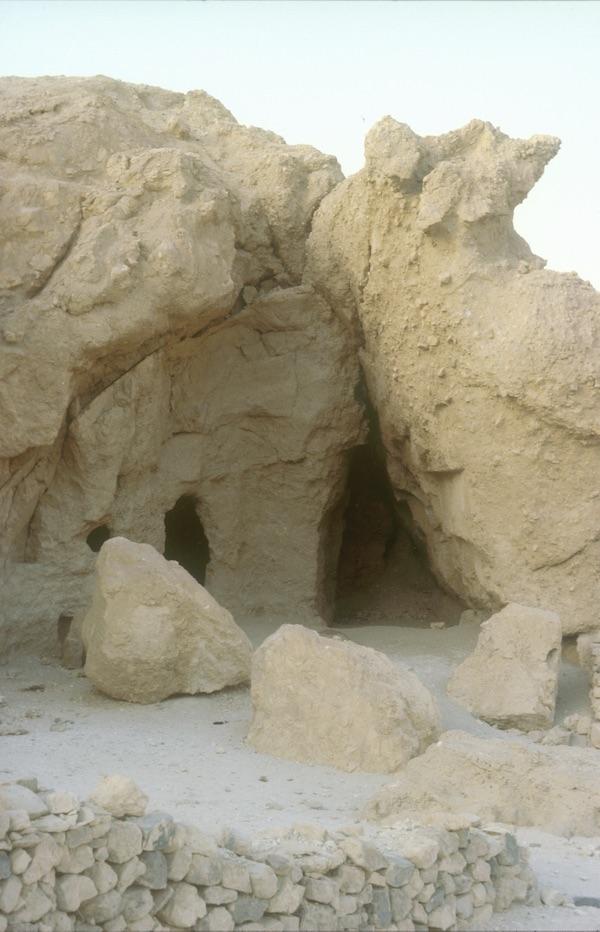

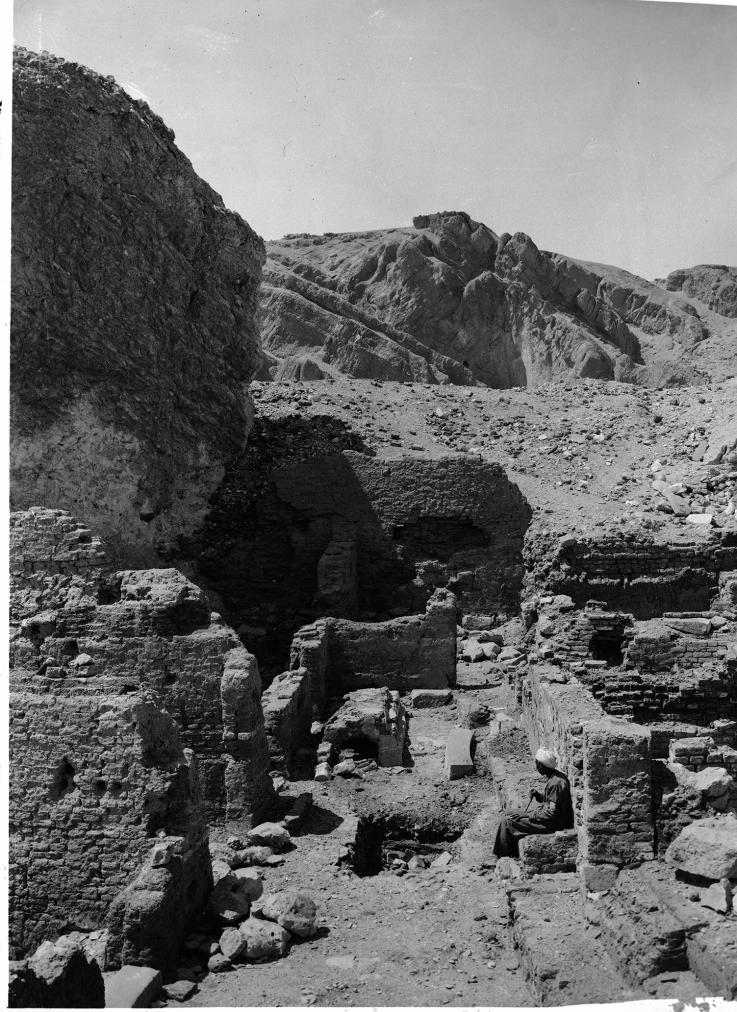

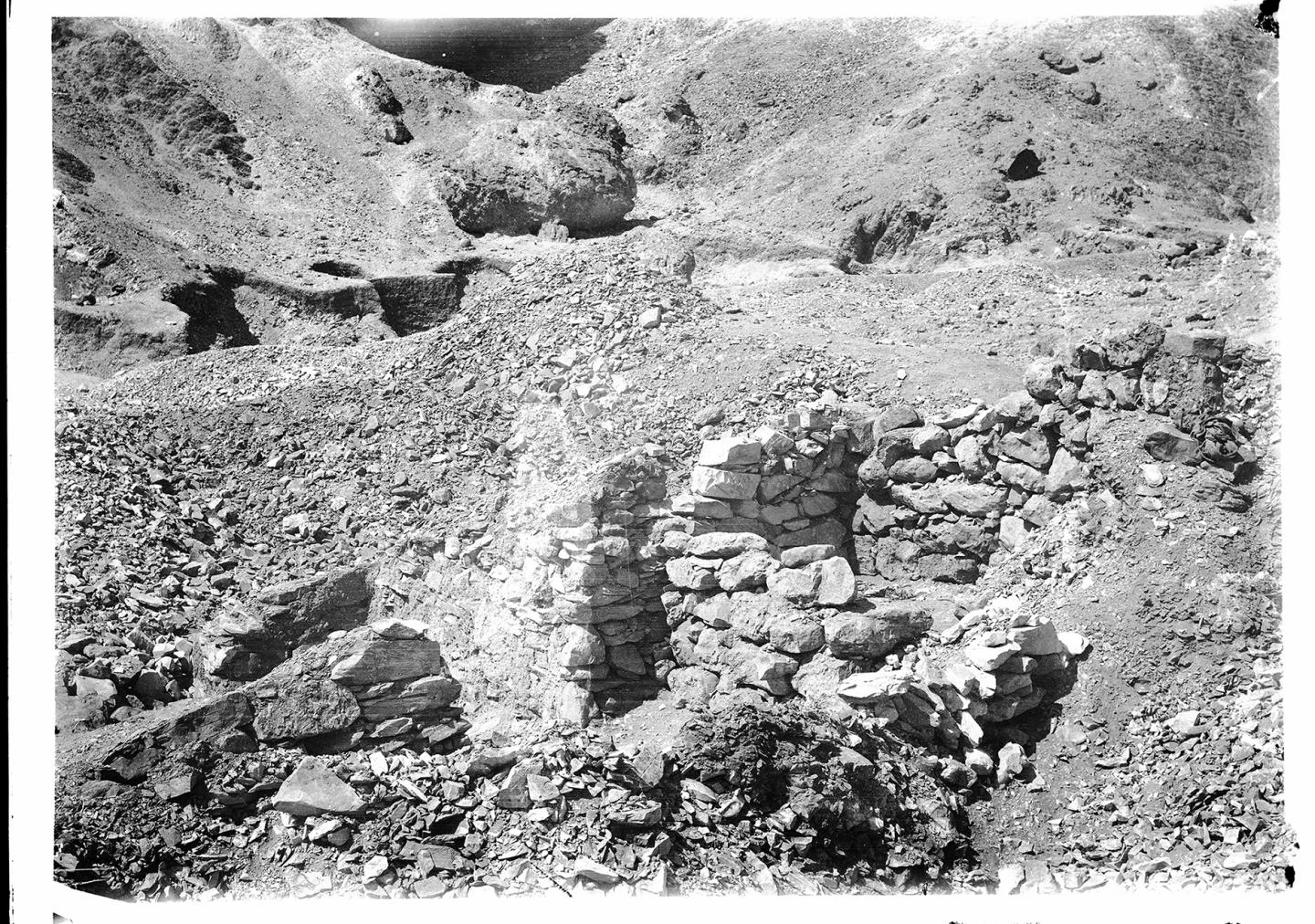

Except for a few Palaeolithic stone tools, there is little evidence of human activity in QV and subsidiary wadis before the 18th Dynasty. Then, perhaps because of the valley’s convenient location, it became an increasingly common site for the burials of minor members of the royal family, gradually replacing the outlying western wadis as the principal burial site. As important as location when determining the burial site for royal family members, Egyptologists believe that a small grotto in the cliffs at the southwestern limit of QV reminded ancient priests of the vulva of the goddess Hathor, an appropriate symbol to accompany the burials of royal children, wives, and mothers. That grotto would fill with water when it rained, then drain along a small, natural watercourse through the middle of QV, emptying into the desert outside the valley’s entrance. QV tombs were dug on either side of this watercourse - 18th Dynasty tombs lay close beside it; early 19th Dynasty tombs clustered at the base of low hills to its southwest; later 19th Dynasty tombs lay to its north; and 20th Dynasty tombs were dug to its south and west. Egyptologists have identified a small dam, believed to have been built in the 20th Dynasty reign of Ramesses III, to divert water that poured from the grotto and threatened low-lying 19th Dynasty tombs. Constructed of roughly-cut local stone, the simple dam stood one meter high and 18 meters long. A large section of it can still be seen today. After the New Kingdom, in Late Dynastic through Ptolemaic times, few tombs were dug in QV, but several earlier tombs were reused, often for multiple burials. Some were filled with as many as a hundred human or avian mummies. Later, QV was ignored - there were neither new tombs dug nor graffiti written on earlier tomb walls. This isolation, however, did appeal to 4th-century CE Christian monks. They built a monastery here, Dayr al-Rumi, and several QV tombs were reused as monastic cells. Other hermitages were established on the adjacent hillside (e.g., in the Valley of Prince Ahmose). This Christian use continued for three centuries, until the coming of Islam in the 7th century AD.

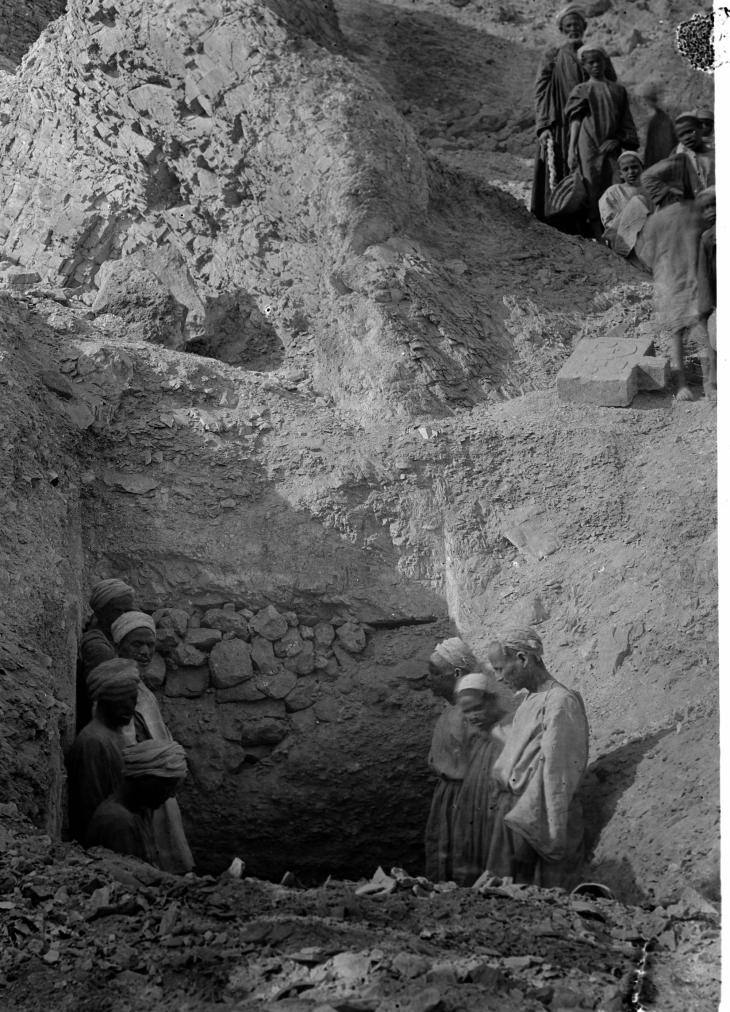

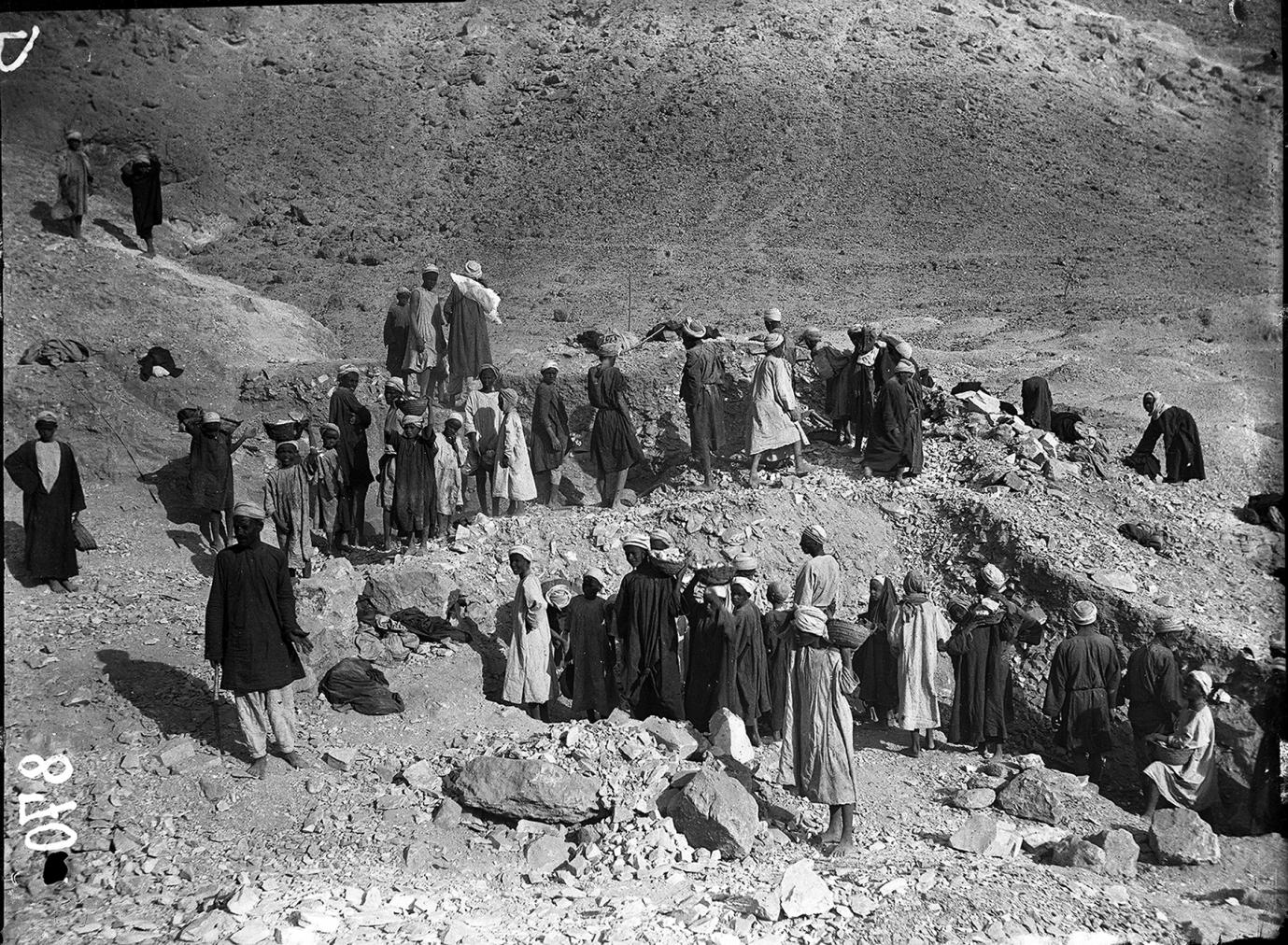

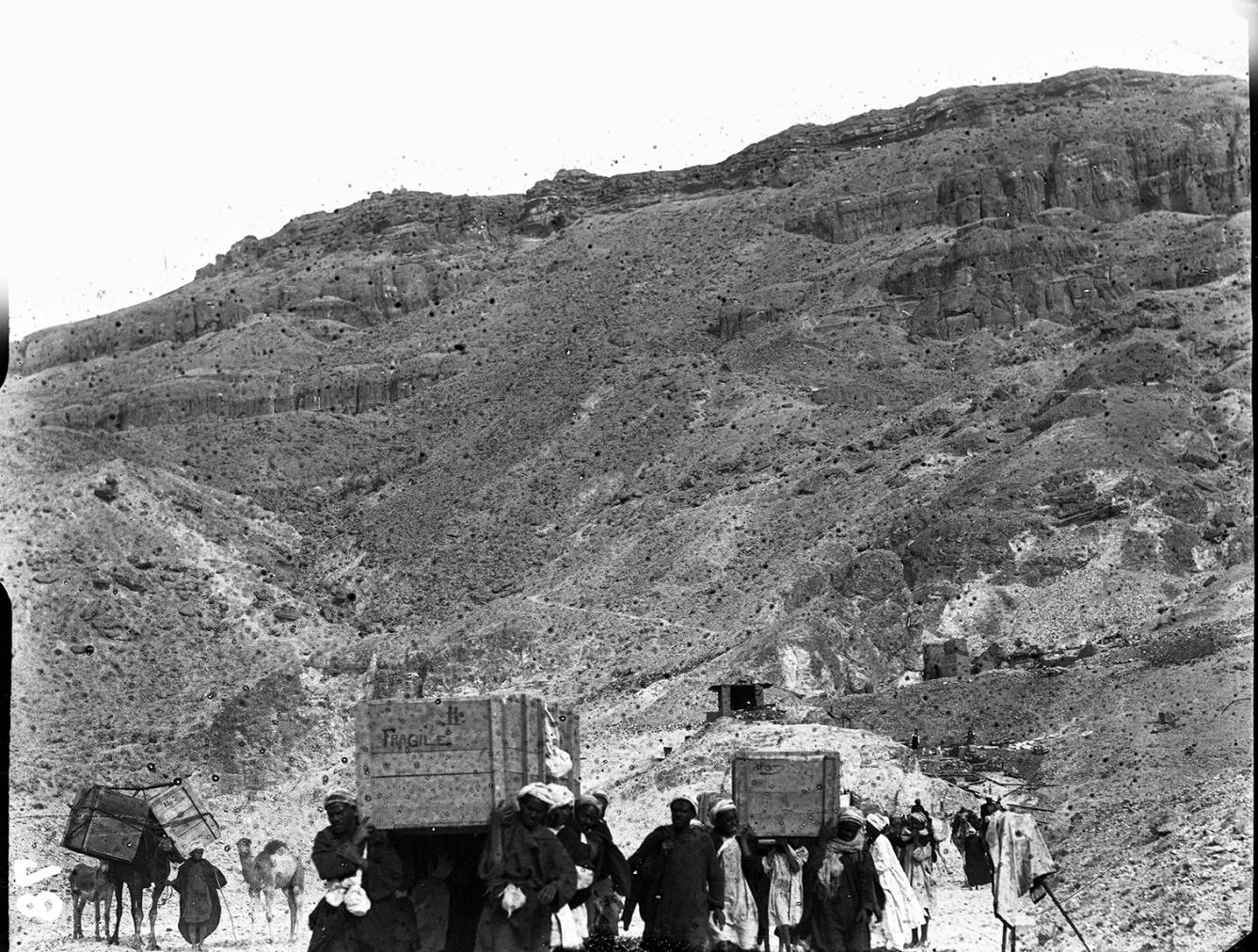

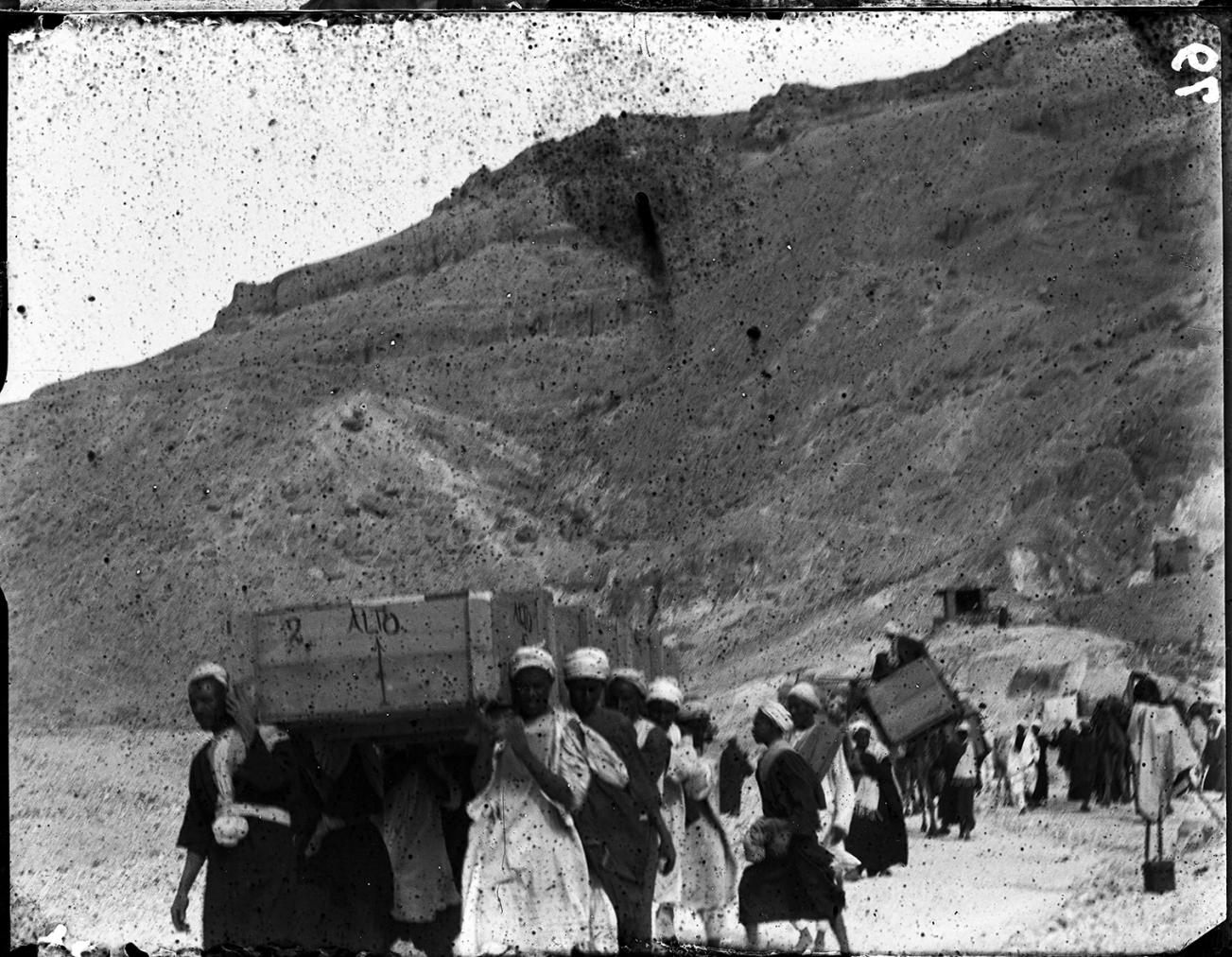

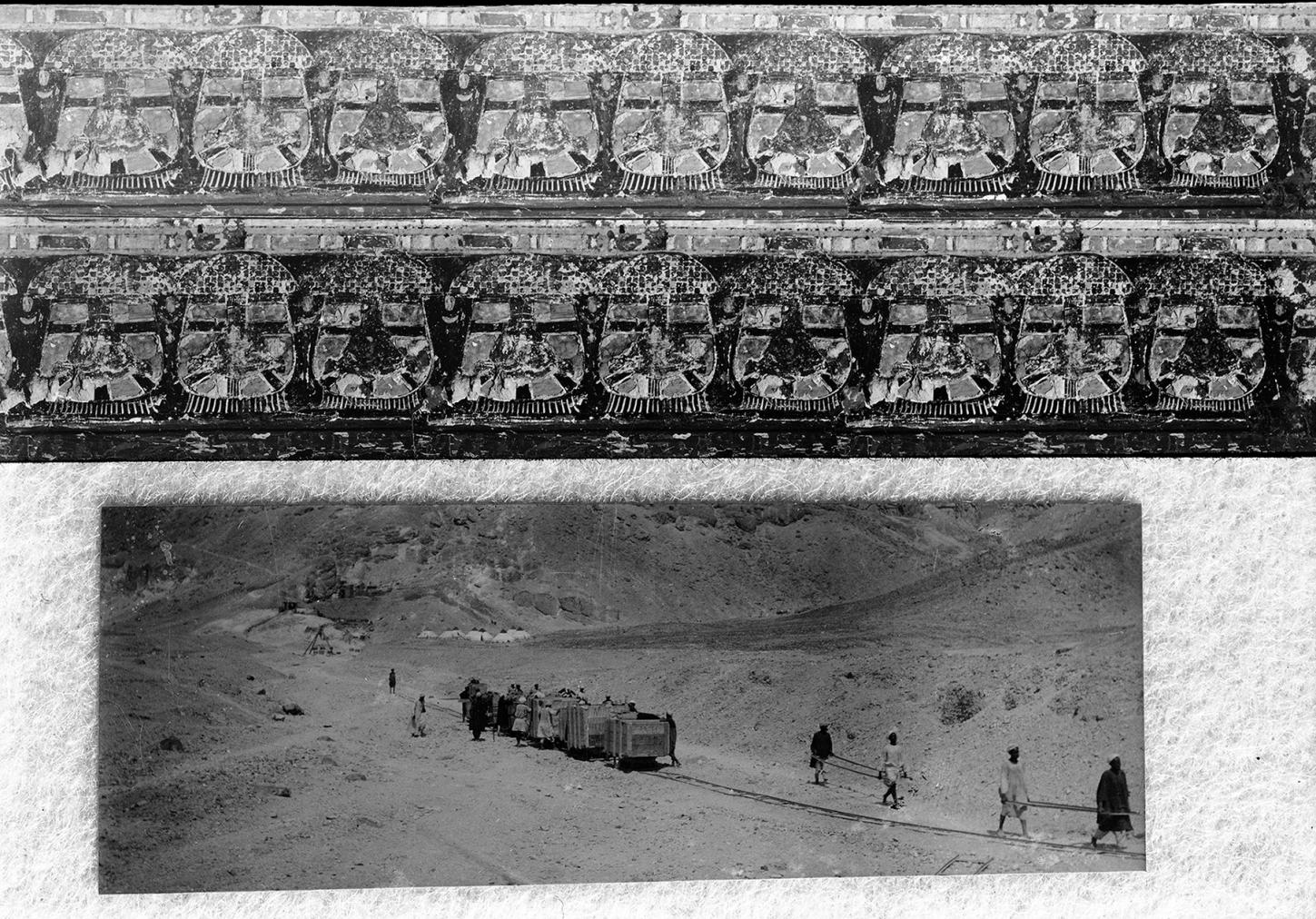

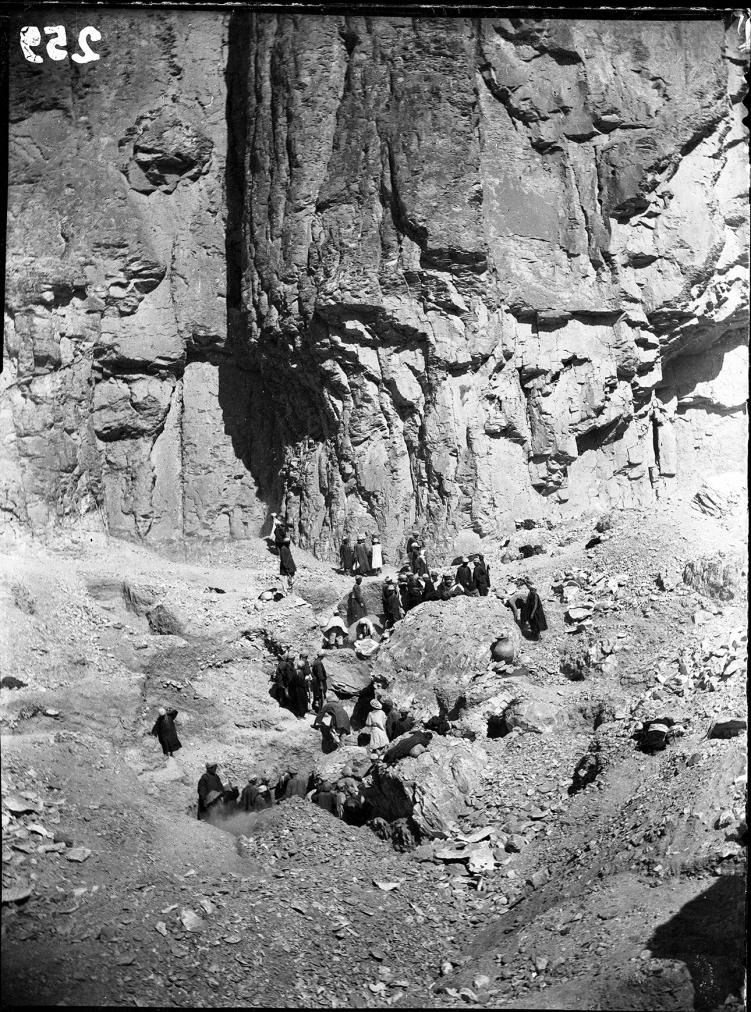

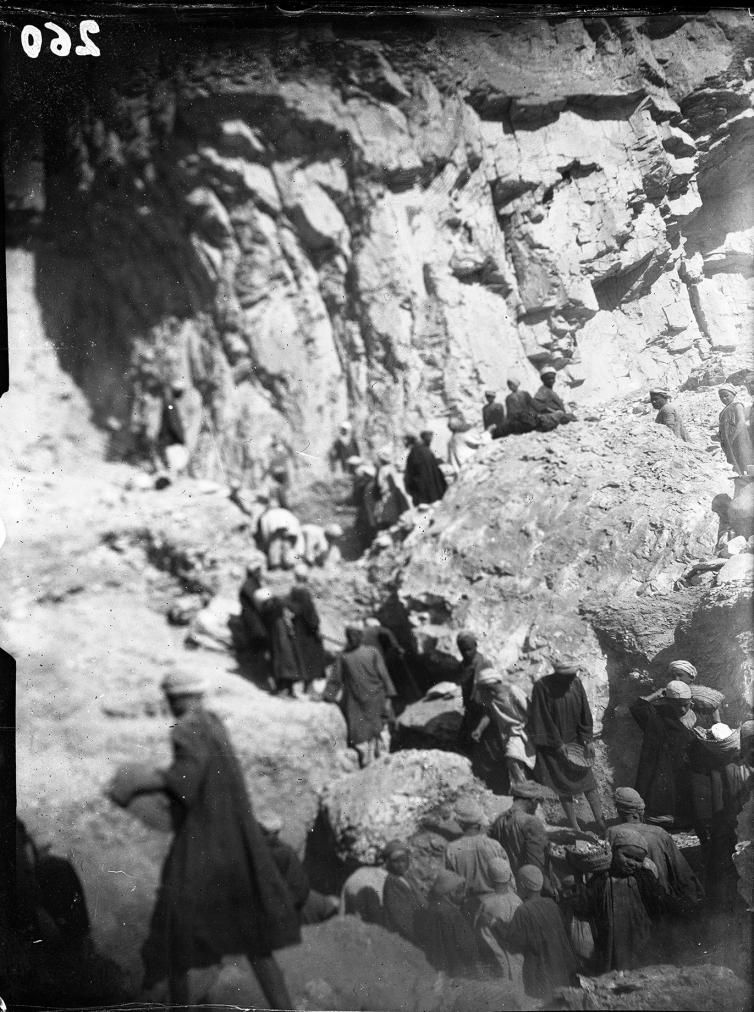

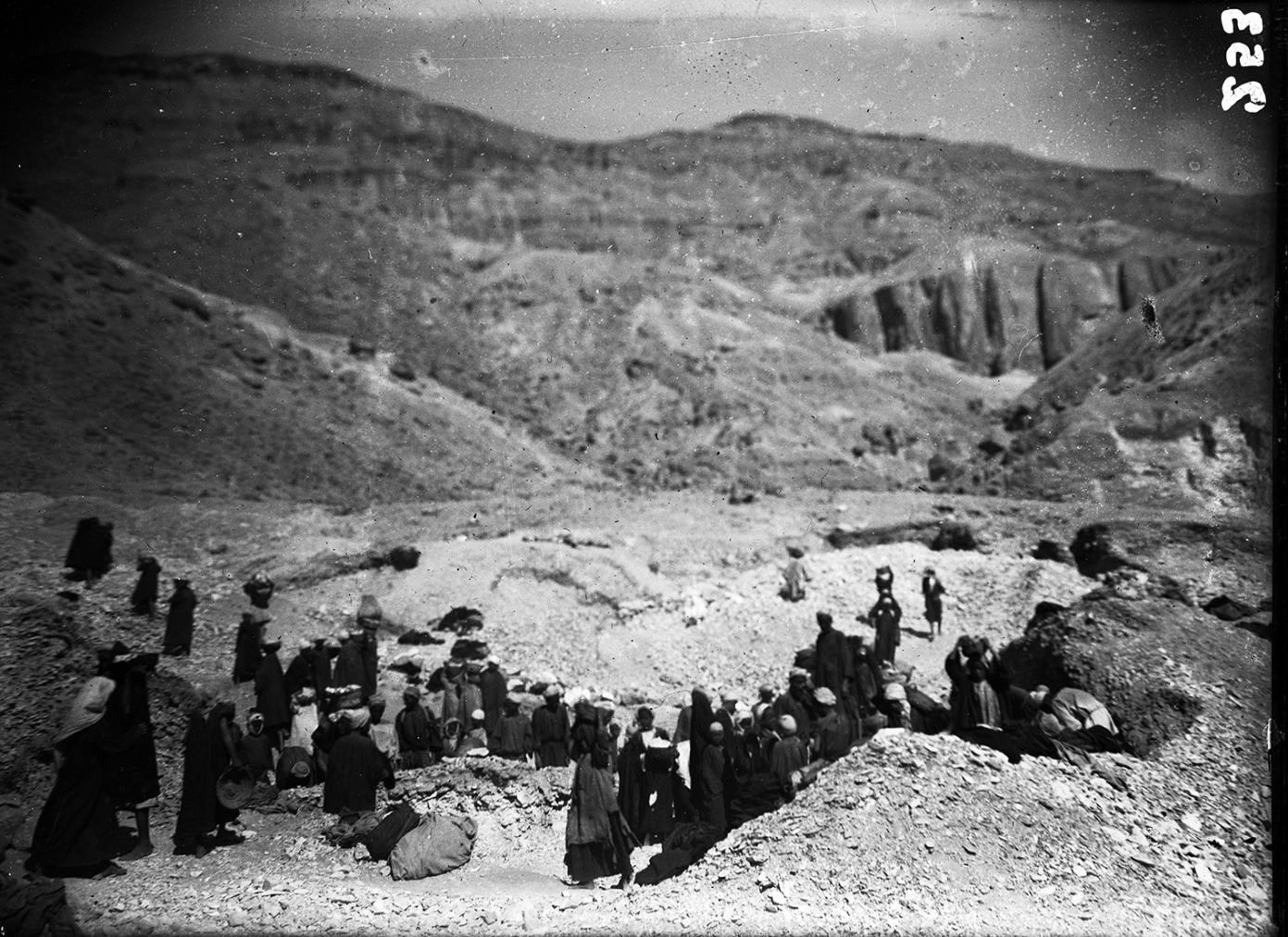

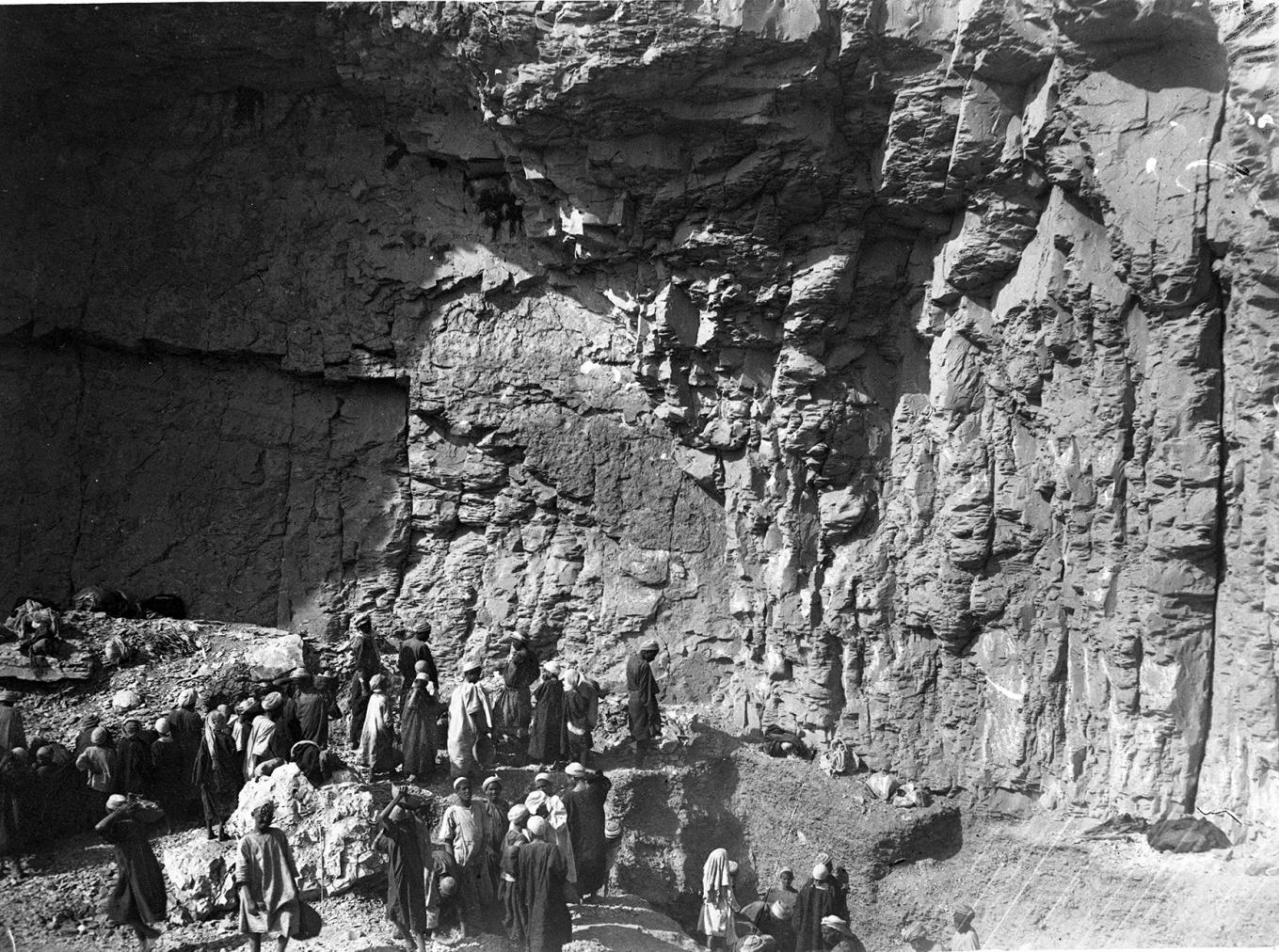

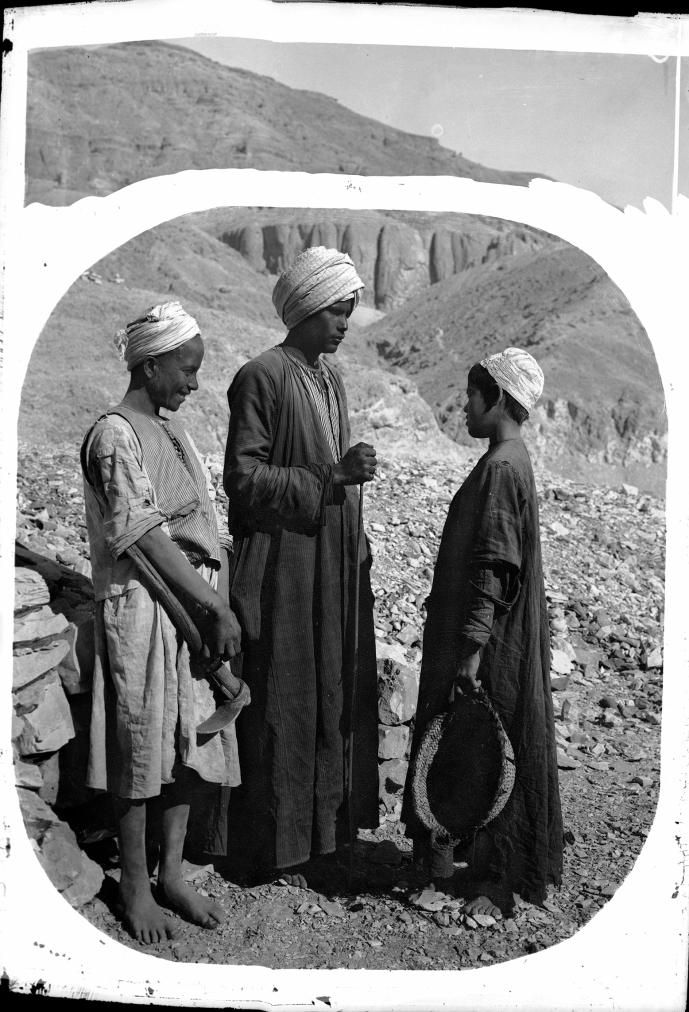

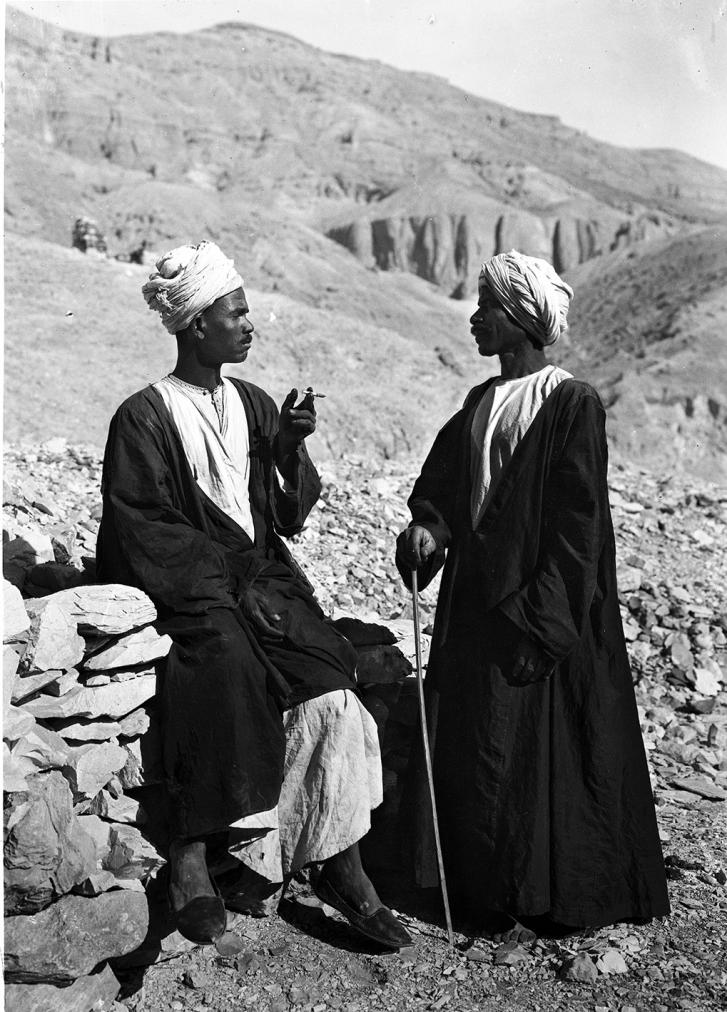

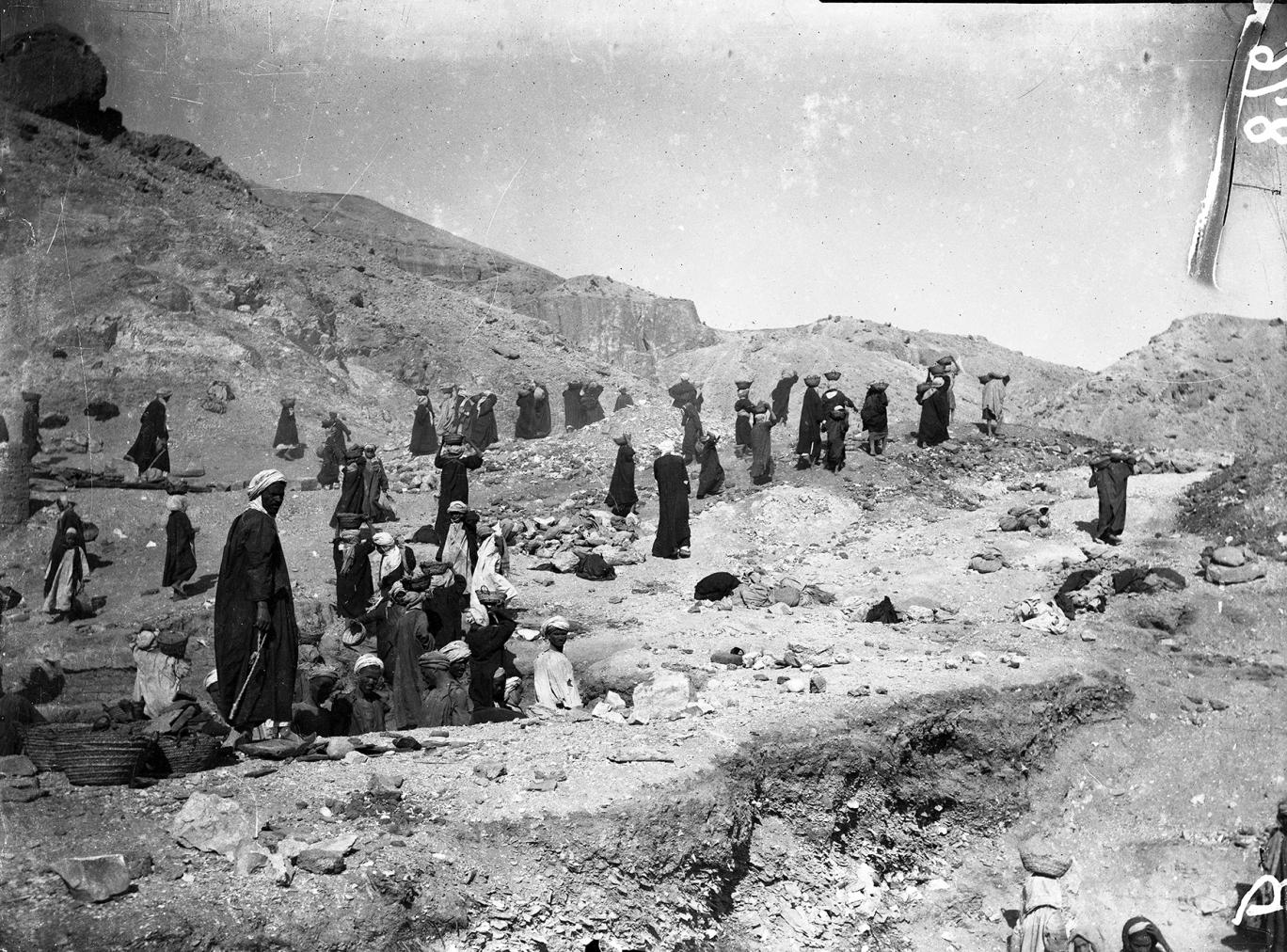

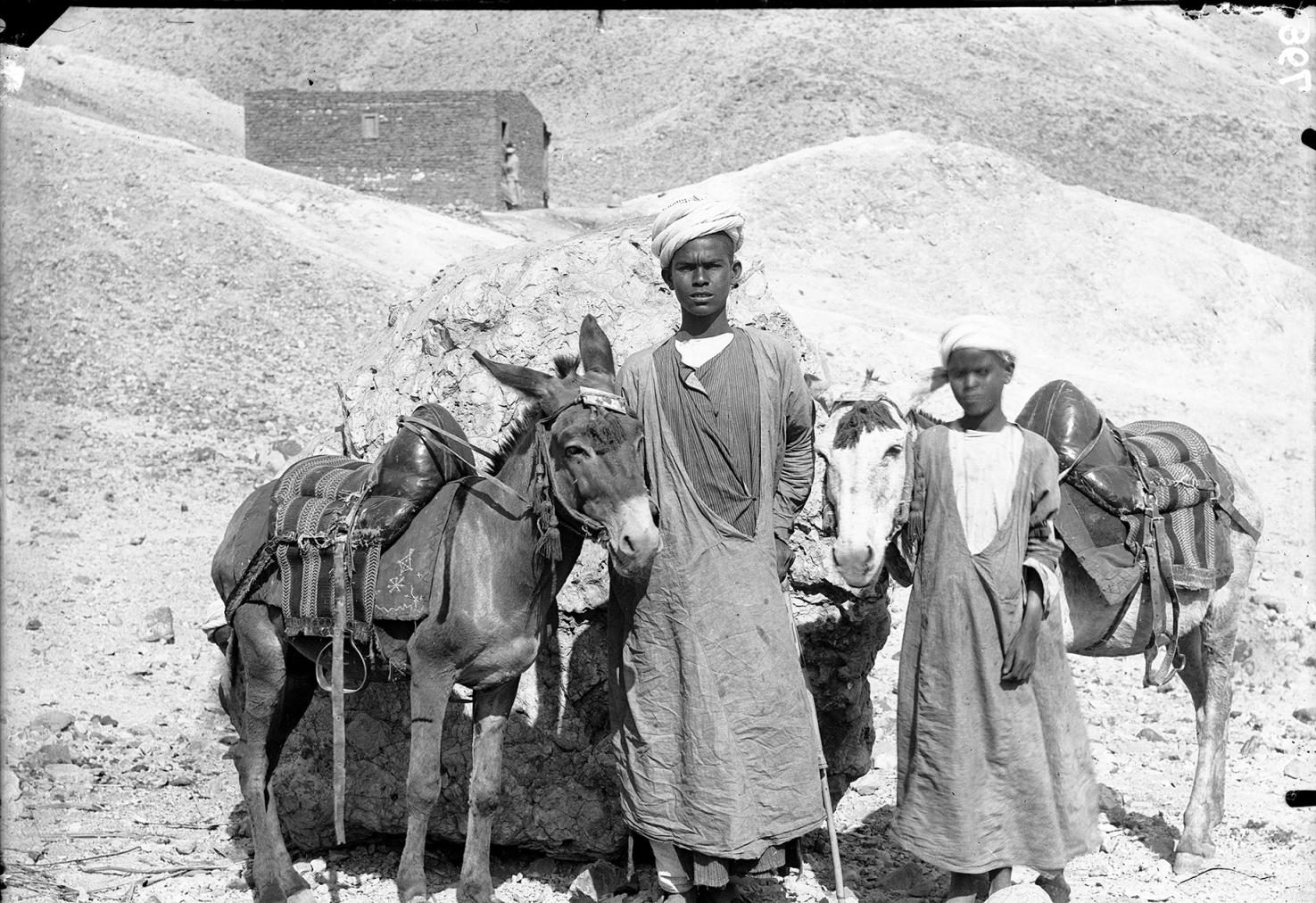

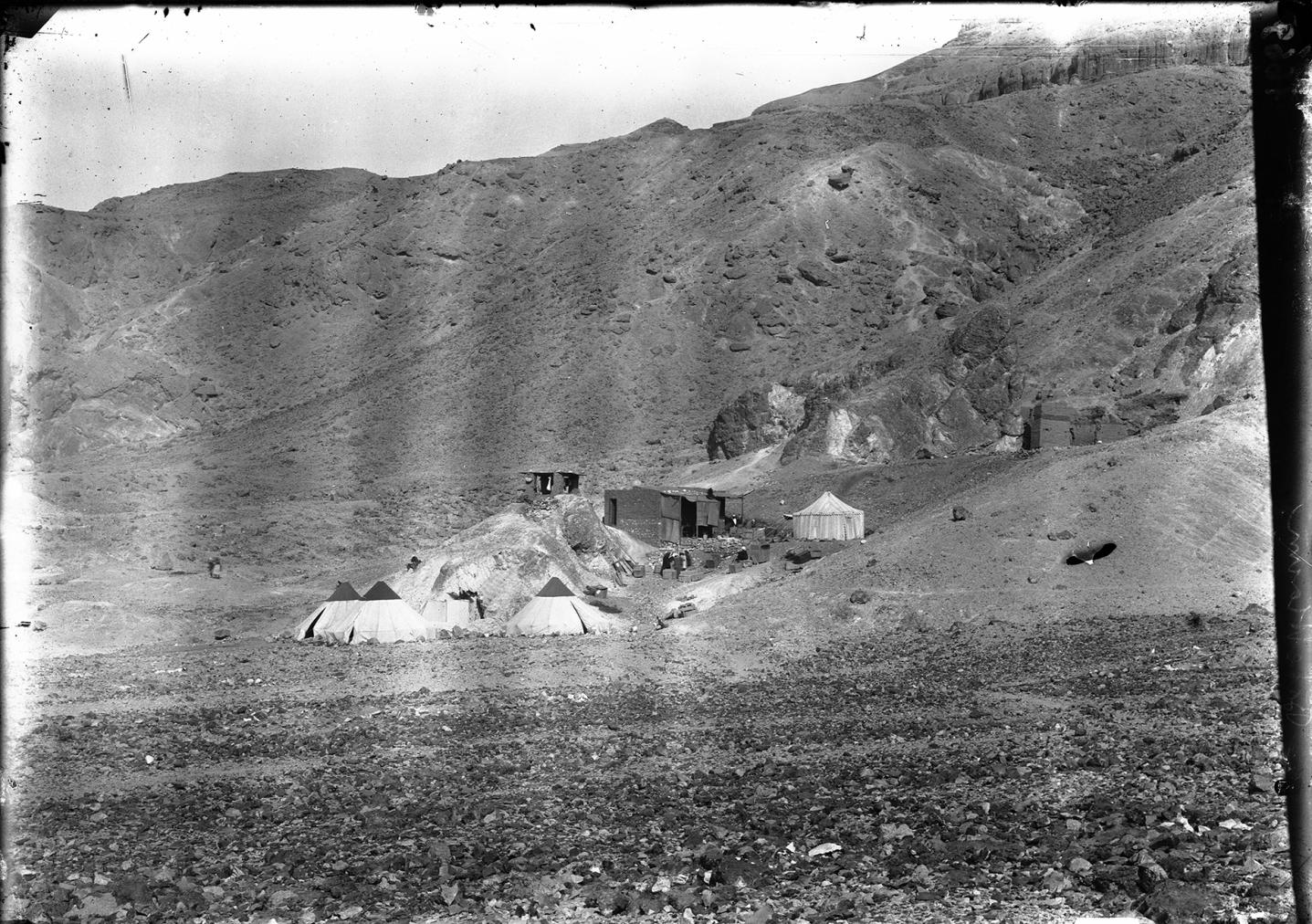

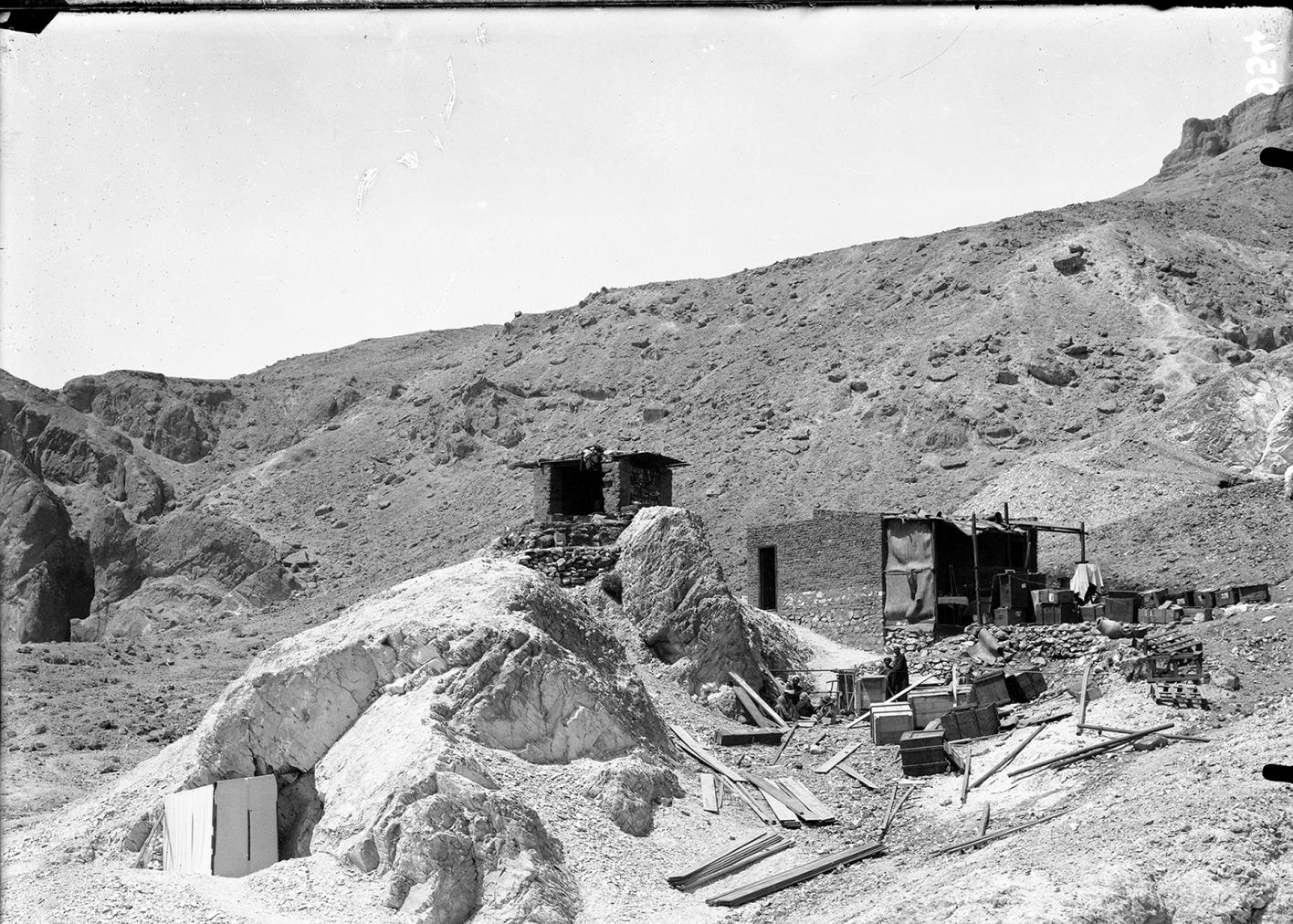

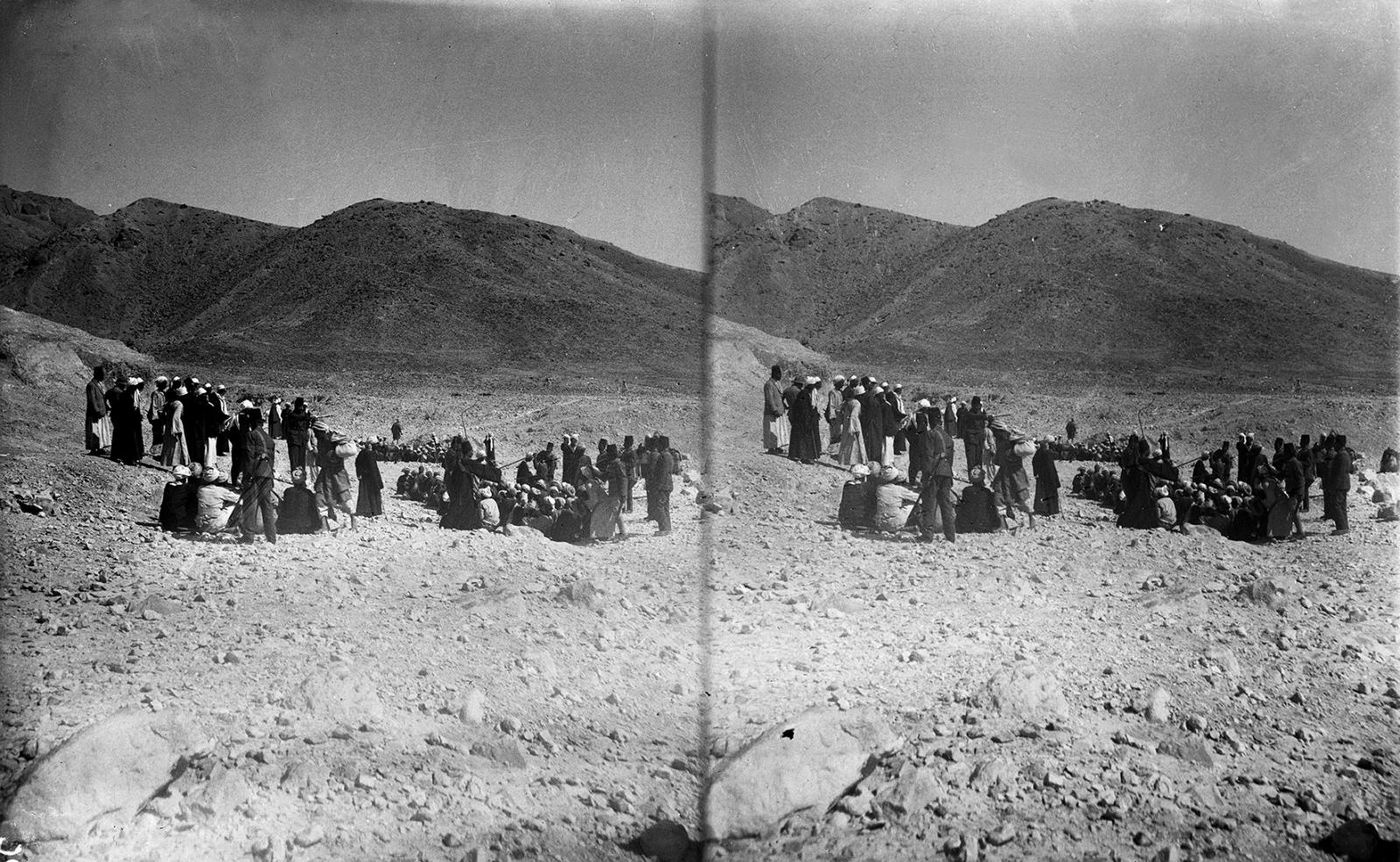

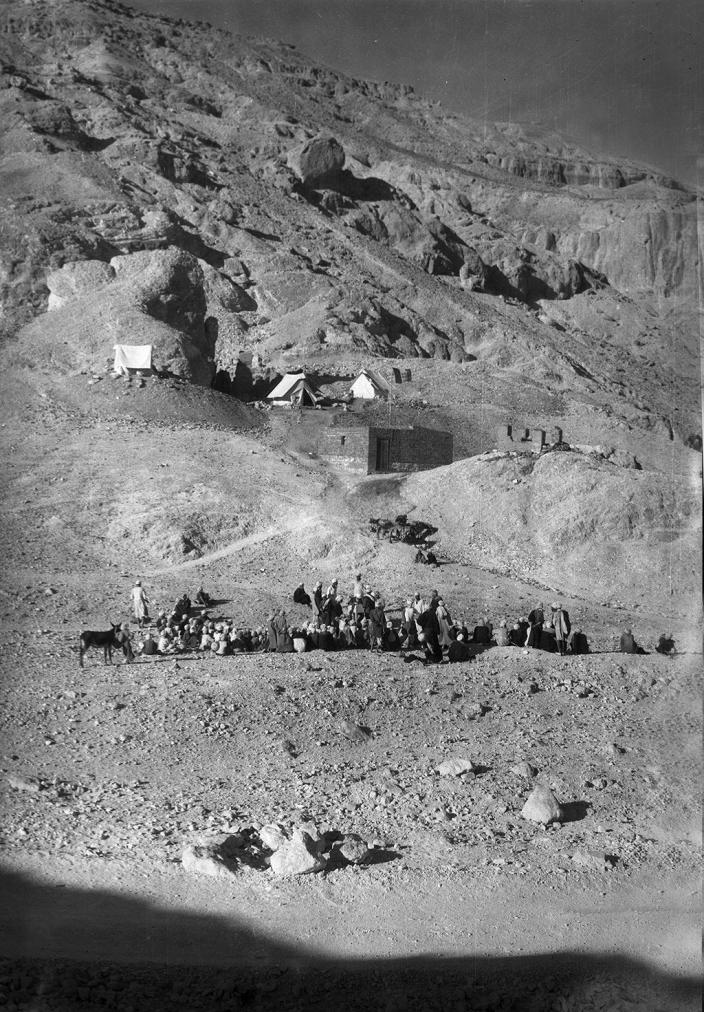

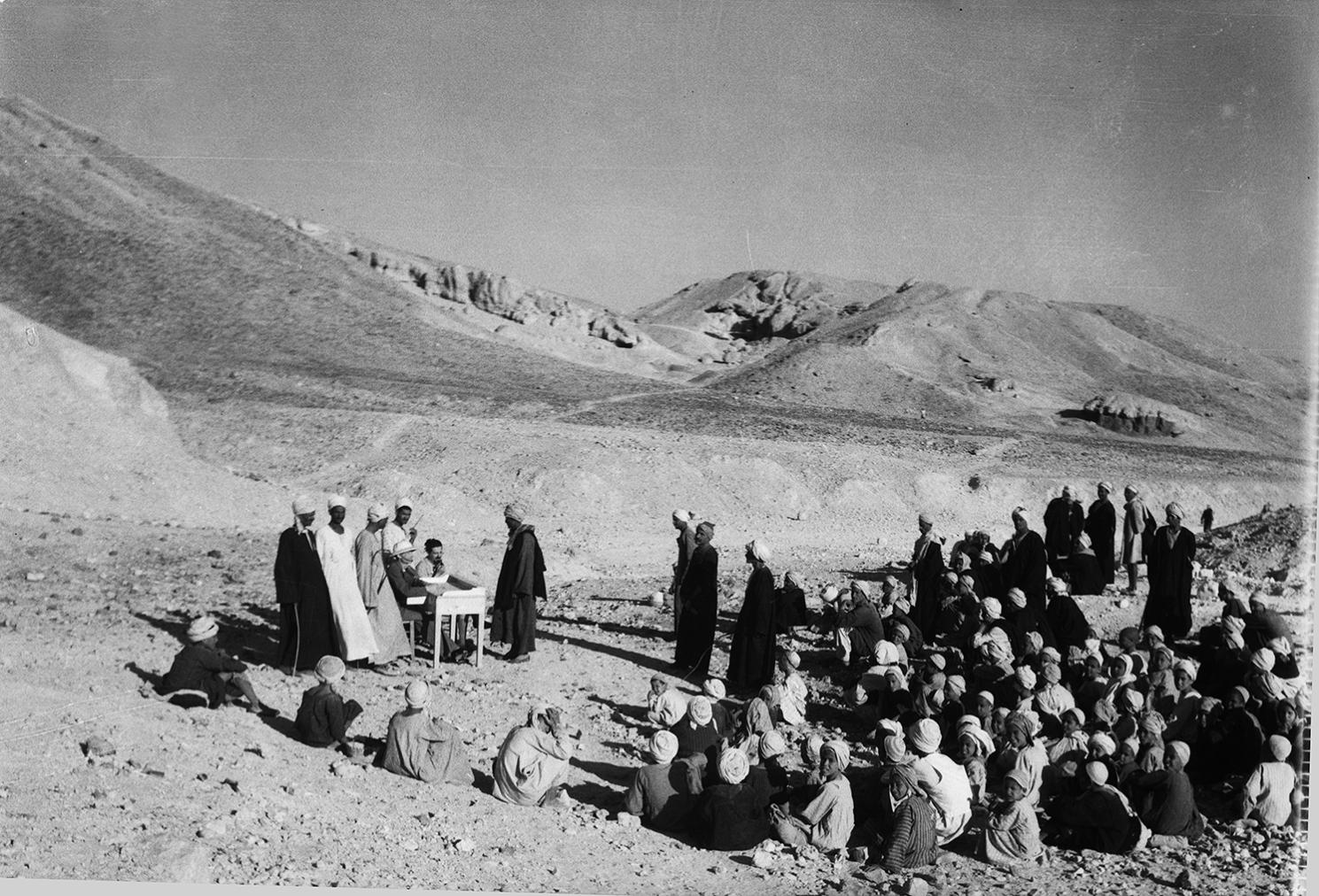

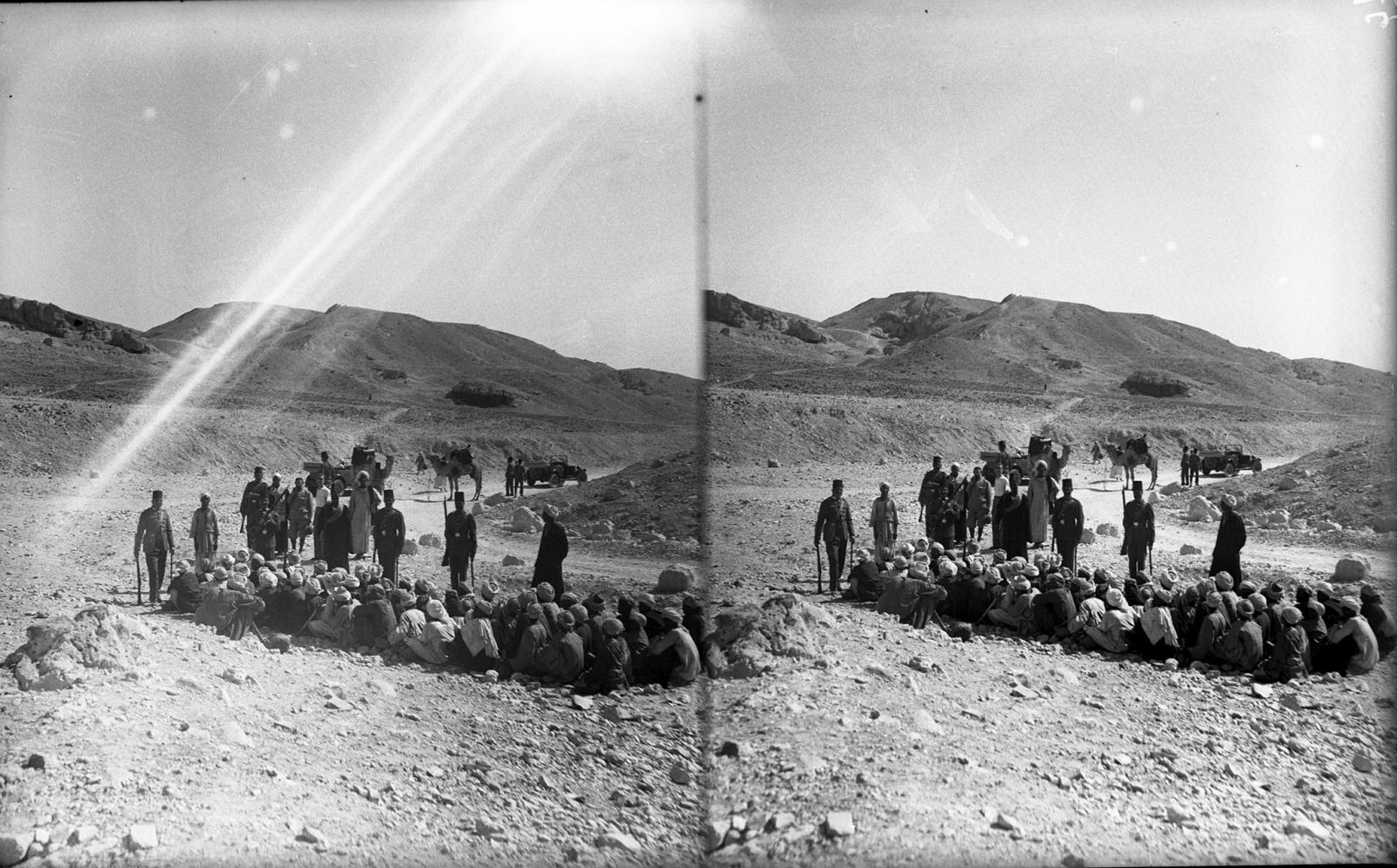

The earliest references we have to modern European visitors in QV and surrounding wadis are from the 19th Century. Jean Jacques Rifaud and Giovanni Battista Belzoni both recorded QV 52 in the early 1800s. Robert Hay of Linplum (1826), John Garder Wilkinson (1828), Jean-François Champollion and Ippolito Rosellini (1829), Karl Richard Lepsius (1844), and Heinrich Brugsch (1854) explored accessible tombs, conducted epigraphic surveys, and documented architectural tomb plans. The first systematic excavation, however, was conducted by an Italian expedition from the Turin Museum, led by Ernesto Schiaparelli and Franceso Ballerini (1903-1905). Their excavations in the QV and subsidiary wadis led to the discovery of the tombs of Nefertari (QV 66) and of the sons of Ramesses III (QV 43, QV 44 and QV 55), the clearing of several 18th Dynasty shaft tombs, and photographic documentation of the landscape, tombs, and finds. Schiaparelli and Ballerini also applied a new tomb numbering system, one that is still in use today. The Italian mission’s work in the area led to the establishment of the largest collection of QV objects at the Turin Museum.

Beginning in the 1970s, a second comprehensive archaeological investigation was undertaken in the QV and subsidiary wadis by a joint Franco-Egyptian Mission – the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Centre d’Etude et de Documentation sur l’Ancienne Egypte (CEDAE) - under the direction of Christiane Desroches Noblecourt and, later, of Christian Leblanc. Their activities, which were largely developed from 1984 to 1994, included epigraphic surveys, architectural and photographic documentation, clearing and exploration of all numbered tombs, and site management efforts. Their research has provided a comprehensive understanding of the use of the area, the identity of many tombs, and the post-pharaonic history of the site.

Several other individuals and projects have conducted surveys, excavations, conservation, and studies in QV and surrounding wadis. The naturalists, Charlies Lortet and Claude Gaillard (1905-1907), surveyed and excavated in Wadi Jabbanat el-Qurud, discovering "hundreds" of mummified baboon remains. Shortly before the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen (KV 62), Howard Carter (1916-1917) surveyed the Western Wadis and excavated in the tomb of Hatshepsut (Wadi A-1). Émile Baraize (1921), after which tomb Wadi A-2 is named, surveyed and excavated tombs Wadi A-1 and Wadi A-2. Elizabeth Thomas (1959-1960) undertook an exhaustive survey and study of tomb architecture in the Valley of the Queens, subsidiary wadis, as well as the Western Wadis and published her findings in Royal Necropoleis of Thebes (1966). Shortly afterwards, the CEDAE (1967-1975) undertook an extensive epigraphic survey of graffiti in the Western Wadis. The Theban Mapping Project (1981-1982), under the direction of Kent Weeks, surveyed sixty-one accessible tombs. The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in collaboration with the Egyptian Antiquities Authority (EAO) began a project for the conservation of the wall paintings of the tomb of Nefertari. The project took place from 1986 to 1992, with environmental monitoring and periodic evaluations of the condition of the wall paintings continuing until 1996. In 1988, the Metropolitan Museum of Art conducted excavations and studies in the tomb of the three foreign queens (Wadi D-1).

Ongoing conservation work in the QV and subsidiary wadis is being carried out by a joint mission between the GCI and Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) and has resulted in a comprehensive QV conservation and management plan. Excavations and surveys have also continued in the Western Wadis, most notably by a joint mission by the Cambridge Expedition to the Valley of the Kings and the New Kingdom Research Foundation (2013-present).

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Conservation

Conservation History

Much of the conservation measures enacted have taken place in the Valley of the Queens. The poor quality of the limestone in the area and internal rock movement pose a threat to the stability of the tombs. Several of the 18th Dynasty shaft tombs have been reburied and the vast majority now have modern masonry surrounds to mitigate erosion. Reconstructions of pillars in larger 19th and 20th Dynasty tombs and the installation of shoring mitigate the effects of internal rock movement.

Other Steps have been taken to mitigate the negative affects of tourist visitation. Paths bordered by rubble retaining walls control the flow of tourists, and shelters have been erected at QV 51, QV 55, QV 44, and QV 66. New signage was installed at the open tombs by the Supreme Council of Antiquities and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. An air circulation system was installed in QV 66, which now requires a separate ticket to visit and tourists are limited to 15 minutes inside. The open tombs, QV 44, QV 52, and QV 55, have plexiglass panels to protect the reliefs from the hands of visitors and wooden flooring to protect the floors.

Flash flooding is a serious threat to the low lying tombs in the area (mostly 18th Dynasty shaft tombs) and has prompted the construction of shelters over the entrances of tombs endangered by flood cascades. Flood deflection walls built around tomb entrances also protect from the effects of torrential rains.

Between 2006-2011 the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in partnership with Egypt's Ministry of State for Antiquities undertook detailed and comprehensive planning for the conservation and management of the Valley and to jointly implement the results of the plan. Prior to this, from 1986 to 1992, the GCI worked with Egyptian colleagues and an international team on the conservation of the wall paintings in the tomb of Queen Nefertari (QV 66).

The aim of the Valley of the Queens project was to tackle threats and impacts to the site in a comprehensive program that addressed flood mitigation, tomb stabilization and protection, conservation of wall paintings and site elements, site and visitor management, and site and visitor infrastructure. This also included training for Egyptian personnel in areas of wall paintings conservation and management of archaeological sites; and was coordinated closely with other groups working in the West Bank to promote an integrated approach to the conservation of ancient Thebes.

The Queens Valley Project was conceived in two phases and has resulted in a comprehensive QV conservation and management plan. Phase 1 of the project (2006—2010) involved comprehensive research, planning and assessment, culminating in the development of detailed plans, and architectural and engineering drawings. Phase 2 of the project, implementation of these plans, was intended to begin in 2011. Only conservation of the wall paintings in many of the tombs has been undertaken to date. The bulk of the intended implementation was interrupted by events in Egypt in 2011 and again in 2013.

Site Condition

The principal problems and threats that are impacting the long-term preservation and integrity of the Valley of the Queens include rock collapse in many tombs and extensive damage with loss of original wall paintings due to geological anomalies of the site in conjunction with flash flooding in the past; extensive reuse of the tombs in late antiquity - the Third Intermediate, Roman, and Coptic periods - resulting in significant damage from fire and alteration; deterioration and defacement of paintings in many tombs as a result of inhabitation by bat colonies; the rise of mass tourism to the site causing extreme overcrowding and uncomfortable conditions within the tombs; and poor presentation of the site and tombs and lack of interpretation of the site, including its post-pharaonic use and wall paintings. Underlying all these problems is the absence of effective site management to ensure the site's long-term sustainability.

Tombs in the Subsidiary Wadis and Western Wadis are also in danger of flooding. These tombs are also not protected by modern entrances and are susceptible to erosion and unpermitted visitation.

Hieroglyphs

Valley of the Queens

The Place of Beauty

tA st nfrw

The Place of Beauty

tA st nfrw

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Latest Discovery in Wadi C (2022)

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

Bibliography

Abdel Fatah, Ahmed, Edda Bresciani, Sergio Donadoni and others. Annibale Evaristo Breccia in Egitto. Vol. II. Cairo: Egyptian Ministry of Culture, 2003: 16-18.

Abitz, Friedrich. Ramses III. in den Gräbern seiner Söhne (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 72). Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätverlag and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986.

Aboudi, Mohamed. . 4th ed. Cairo: C. Tsoumas & Co, 1946.

Agnew, Neville and Martha Demas. Envisioning a Future for the Valley of the Queens: The GCI and SCA Collaborative Project. Conservation: The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter 23 (2008): 20-23.

Asensi Amorós, M.V. Woods from ancient Egypt: The Ramesseum and the Valley of the Queens (18th Dynasty-Roman Period): A preliminary report. In: Thibault S. (ed.), Charcoal Analysis: Methodological Approaches, Palaeo-ecological Results and Wood Uses. Proceedings of the second International Meeting of Anthracology, Paris, September 2000. BAR International Series 1063. Archaeopress: Oxford, 2002: 273-277

Aston, D.A. The Theban West Bank from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty to the Ptolemaic Period. In: Nigel Strudwick, and John H. Taylor (Eds.). The Theban Necropolis: Past, Present and Future. London: British Museum, 2003: 138- 63.

Aubry, Marie-Pierre, Christian Dupuis, Holeil Ghaly, Christopher King, Robert Knox, William A. Berggren, Christina Karlshausen, et al. Geological Setting of the Theban Necropolis: Implications for the Preservation of the West Bank Monuments. In: David A. Aston, Bettina Bader, Carla Gallorini, Paul T. Nicholson, and Sarah Buckingham (eds.). Under the Potter's Tree: Studies on Ancient Egypt Presented to Janine Bourriau on the Occasion of Her 70th Birthday, pp. 81-124. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 204. (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2011). Pp. 81-124.

Augé, Christian and Guy Lecuyot. Deir er-Roumi. Étude du matiériel numismatique. Memnonia 9 (Cairo, 1998): 107-119.

Bagnall, Roger S., and Dominic Rathbone. Egypt: From Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004.