The village of Dayr al Madinah, home to the workmen who excavated and decorated the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, was probably founded during the reign of Thutmes I. His name was found stamped on the many bricks of the first enclosure wall of the village. But Amenhetep I and his mother Ahmes Nefertari were traditionally called its patrons, which may indicate that there was at least a small settlement here during their reign. The village remained in use throughout the New Kingdom (except during the Amarna Period).

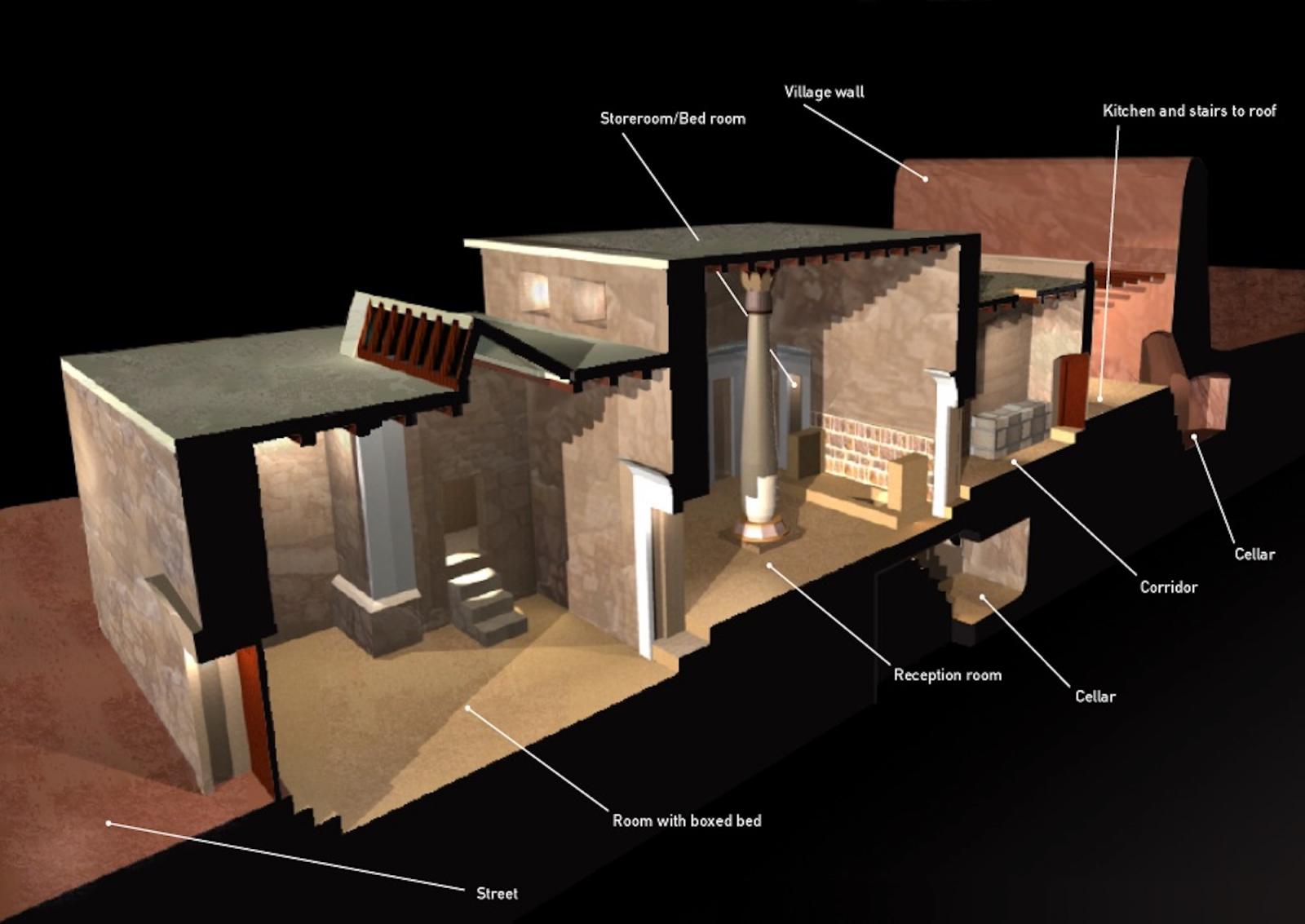

Dayr al Madinah is located in a small valley southeast of the Valley of the Kings and northeast of the Valley of the Queens. The village, which was systematically enlarged during the New Kingdom, consisted of one main street along a north-south axis, and a few side alleys. The houses - there were about seventy of them - each had an entrance hall that also functioned as a private chapel, followed by a columned living area that gave access to a small cellar, used for storage. The main room led to smaller rooms, perhaps used as sleeping quarters, and sometimes a staircase led to the roof. At the back of the house an open space was used as a kitchen.

The workmen of the royal necropolis were called the "Servants in the Great Place" or "Servants in the Beautiful Place of the Mighty King" throughout Dynasty 18, and "Servants in the Place of Truth" during the Rameside Period. They were also called the "Men of the Gang," a reference to the Egyptian term ist, meaning "gang" or "crew," a term that came from the Egyptian military and navy. The number of workmen employed on a project varied between 30 and 120, according to the size of the tomb being cut. The men were divided into two groups, a right gang and a left gang. Two foremen and their deputies were appointed to supervise each gang. Scribes kept detailed records of each workman's attendance, accounts of salary payments, and records of any material removed from the royal storerooms.

The working day was divided into two shifts of about four hours each. The week was composed of eight working days followed by two days of rest. During these, the workmen returned to their homes to attend to personal affairs. They might also have spent the night in a settlement of huts located on the col of the mountain between the village and the Valley of the Kings.

If a tomb was completed prior to the death of its royal owner, the workmen were assigned to work on the tombs of queens and royal children in the Valley of the Queens and sometimes even on the tombs of noblemen. As time permitted, workmen could build their own tombs, adjacent to the village of Dayr al Madinah.

The daily life of the workmen and their family is well-known thanks to the vast number of documents found at Dayr al Madinah. Thousands of Ostraca, numerous stelae, graffiti, and about two hundred documentary and literary papyri describing daily activity were recovered from the village and the Valley of the Kings.

In chamber 2 of KV 5, the Theban Mapping Project found an ostracon written by the scribe Qenherkhepeshef. According to Egyptologist Rob Demarée, the ostracon is a receipt for oil lamps used to light the work in this tomb. Because of the ostracon's distinctive handwriting, Demarée was able to identify its scribe as the well-known Qenherkhepeshef, who oversaw much of the building work of Rameses II. He was born during the reign of Rameses II, and lived until the first year of the reign of Siptah. Qenherkhepeshef's father was Panakht, but he also seems to have been adopted by Ramose, another scribe. According to ancient documents, Qenherkhepeshef was not especially popular. He was accused of corruption and of using royal workmen for personal projects.

Qenherkhepeshef and his descendants collected a large library of papyri that were recovered from the cemetery at Dayr al Madinah by French excavators in 1928. It included official letters, religious texts, tales, poetry, medical and magical texts.