QV 53

Prince Rameses-Meryamen

Entryway A

See entire tombA short, wide Ramp that provides access to the tomb. Modern masonry walls lie to either side of the ramp and above the entrance. At the end of the ramp, the original walls were finely worked, creating a flat, even wall surface. A thin layer of original plaster survives in this area.

Gate B

See entire tombThis gate provides access to vaulted chamber B. Slots were cut into the lintel and upper jambs of the doorway. A metal grill door with mesh has been installed over this gate to prevent access to the tomb. The gate has no surviving decoration.

Chamber B

See entire tombThis chamber lies perpendicular to the tomb's axis and has a Vaulted ceiling. The walls and ceiling are severely blackened by fire.

Little surviving decoration remains. The northern wall has remains of a Kheker frieze, the northwestern wall contains remains of a Djed pillar and a standing deity, and the southwestern wall has the remains of Rameses III and a deity. We can assume from the iconographic repertoire of the other tombs of the sons of Rameses III, that the walls in this chamber would have had scenes of the king and the prince offering to and adoring various deities.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate C

See entire tombThis gate lies on axis with the tomb's entrance and provides access to the burial chamber. A pivot hole on the right side of the doorway indicates that this gate would have been closed by wooden double-doors. There are remains of a mud brick structure in the threshold of the door, possibly from later reuse.

The only remaining decoration includes parts of a Kheker frieze on the upper parts of the right reveal and text on the right outer thickness indicating that it had an image of Nephthys performing the Nini ritual.

Porter and Moss designation:

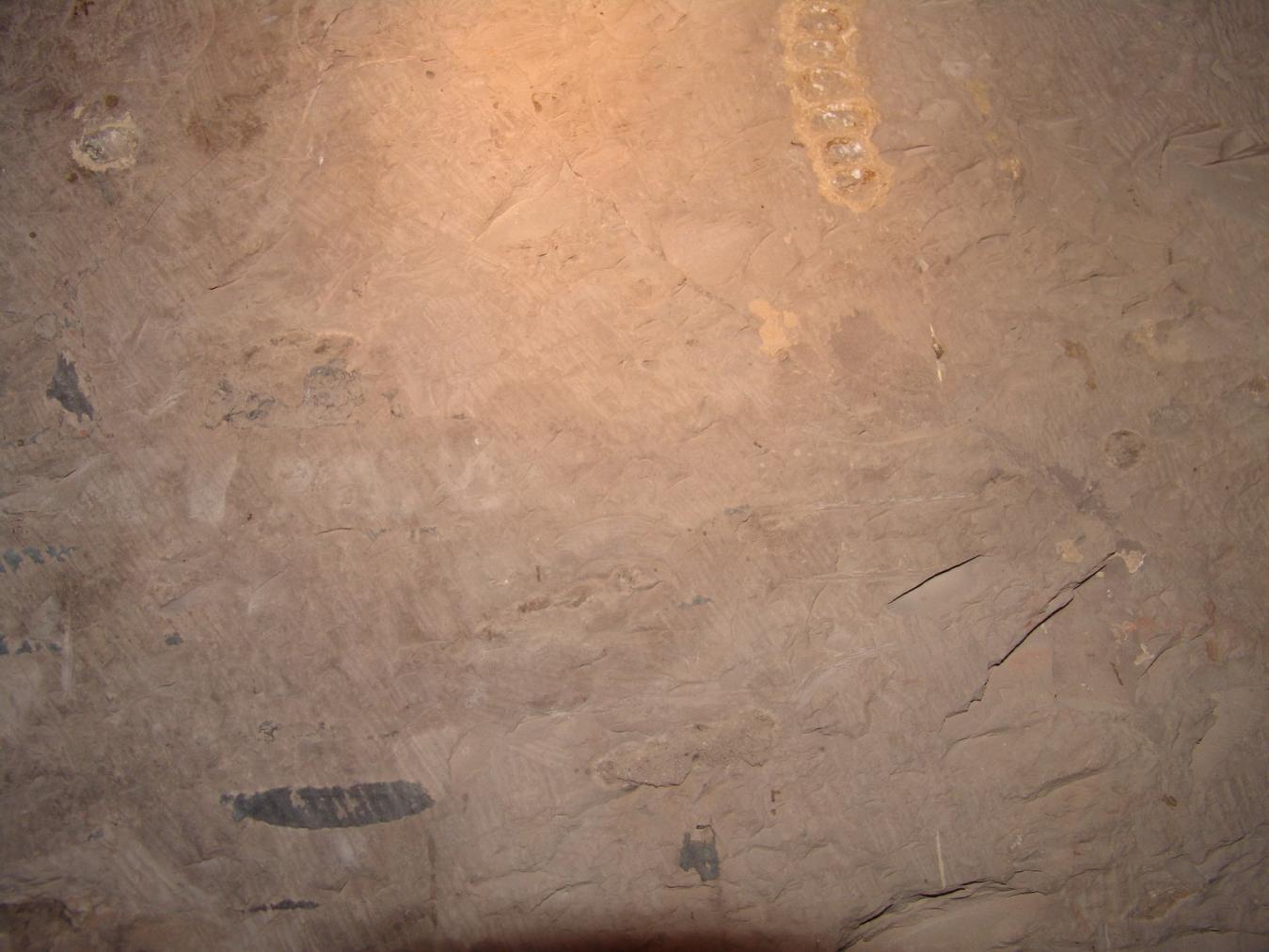

Burial chamber C

See entire tombThis corridor served as the burial chamber of the tomb, indicated by the sunken pit cut into the center of the chamber's floor for the Sarcophagus. Burial chamber C lies on axis with the tomb's entrance and has two undecorated side chambers, one to the southeast and one to the northwest. The walls in this chamber have suffered due to flood damage

The decoration in this chamber indicates that it was added in two phases. The original limestone was first decorated with shallow painted relief and then redressed and covered by sculpted and painted plaster. While there is little that survives today, the remains indicate that the walls were decorated with scenes from the Book of the Dead, specifically gates 1 to 4.

Chamber plan:

RectangularRelationship to main tomb axis:

ParallelChamber layout:

Flat floor, no pillarsFloor:

One levelCeiling:

Flat

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Ca

See entire tombThis gate is cut into the southeastern wall of the burial chamber and provides access to a small side chamber. The gate was not decorated.

Side chamber Ca

See entire tombThis side chamber lies to the southeast of the burial chamber. The walls were plastered but not decorated.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Cb

See entire tombThis gate is cut into the northwestern wall of the burial chamber and provides access to a small side chamber. The right jamb of the door is destroyed and the gate was not decorated.

Side chamber Cb

See entire tombThis side chamber lies to the northwest of the burial chamber. The walls were plastered but not decorated.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate D

See entire tombThis gate provides access to a rear, unfinished chamber. It was not decorated.

Chamber D

See entire tombThis chamber lies on axis with the tomb's entrance. It has suffered severely due to flood damage and water marks are visible halfway up the walls. The southeastern side of the chamber is unexcavated and the ceiling has collapsed in the northwestern corner. A large side chamber lies to the northwest.

Although the chamber was not finished, remains of decoration survive on the northeastern wall. This includes an image of Anubis as a jackal reclining on a chapel, followed by remains of the prince and text indicating that Rameses III preceded his son.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Da

See entire tombThis gate is cut into the northwestern wall of chamber D and provides access to a side chamber. The gate was not decorated.

Side chamber Da

See entire tombThis large side chamber lies to the northwest of chamber D. The western and southern corners, as well as the northeastern side of this chamber are unexcavated. The walls have water marks halfway up indicating past flooding events and were not plastered or decorated. A small side chamber or niche was cut into the southwestern wall.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Daa

See entire tombThis gate is cut into the northwestern wall of the side chamber and provides access to a small, unfinished side chamber or niche. It was not decorated or plastered.

Side chamber Daa

See entire tombThis small side chamber or niche lies to the northwest of the larger side chamber Da. It was not finished and parts of the chamber are unexcavated. The walls were not plastered or decorated.

About

About

QV 53 is located on the south side of the main Wadi near its western end. The tomb is entered through a Ramp (A) leading into a barrel vaulted chamber (B), followed by the Burial Chamber (C) with two side chambers (Ca) and (Cb) to the east and west, respectively. Burial Chamber (C) proceeds along the central tomb axis to chamber (D), which has a large side chamber (Da) to the west. A further small niche (Daa) lies to the south of side chamber Da. Remains of a mudbrick structure are present in Gate C, and Burial Chamber C has a sunken pit in the center of the floor for the Sarcophagus. The rock into which the tomb is cut is in relatively good condition and is easily worked, though it has suffered from periodic flooding resulting in localized ceiling and wall loss.

QV 53 is attributed to Prince Rameses-Meryamen, another son of Rameses III. With Khaemwaset (QV 44), he is one of only two sons who carried priestly titles, in his case the "Great chief of Seers". As with the other sons of Rameses III, Rameses-Meryamen is also listed in the Madinat Habu prince list. QV 53 has little extant decoration. The iconography forms part of the integrated depiction of Spell 145 of the Book of the Dead in QV 44, QV 53, and QV 55, with each tomb depicting different scenes from the spell (QV 53 has gates 1-4). The rock surfaces are finely worked in areas, necessitating only a thin layer of plaster. Areas of carved rock can be seen in Burial Chamber C (east wall, north end, and southwest corner), used as preliminary setting out marks for the decoration. Mason tool marks are also still visible on the rock in places. There is fire damage in this tomb, but it is not uniform. Some chambers have blackening while others show heat alteration but no blackening.

The tomb has been accessible since the time of Robert Hay of Linplum (1826) and was cleared by the Franco-Egyptian Mission in 1985-86. According to Jean Yoyotte (1958), the tomb was partially filled with debris, requiring one to crouch or crawl upon entry. Elizabeth Thomas noted the same in 1959-60, suggesting a long history of periodic flooding. Currently the tomb is not open to visitation. A metal grill door with mesh prevents visitor access. Modern masonry retaining walls lie on either side of the ramp and above the entrance.

Noteworthy features:

QV 53 is attributed to Prince Rameses-Meryamen, another son of Rameses III. The iconography forms part of the integrated depiction of Spell 145 of the Book of the Dead in QV 44, QV 53, and QV 55, with each tomb depicting different scenes from the spell.

Site History

The tomb was constructed in the 20th Dynasty, during the reign of Rameses III. It has been reused substantially, first starting the Third Intermediate Period. During the Roman Period (165-180 AD), a plague broke out in the area and infected bodies were covered with lime and buried in QV 53. The lime was apparently used to disinfect the bodies. The blackening of the tomb walls and heat alteration from fire probably occurred during these periods of reuse.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

The modern masonry retaining walls along the Ramp and above the entrance were constructed by the CNRS in 1990, following recommendations to distinguish new interventions (not covered in plaster) from original courses. Burial Chamber C has gypsum mortar fills on the west around Gate Cb and in Gate C. The remains of these repairs are still present despite recent rock loss. Wall painting treatments, carried out by the CNRS in 1985-1986, include edging repairs and large plaster fills that have both a lower grey plaster keyed with cross-hatching, and an upper pink-colored plaster (similar to what was used in QV 51).

Site Condition

According to the GCI-SCA, a fault runs through the rear of the tomb, in chambers Da, D, and a corner of C, which is parallel to the joint planes along which rock loss has occurred, particularly at the gates. Substantial diagonal fractures and open joints are present in ceilings and walls throughout the tomb, especially in the central burial chamber (C), which often results in localized rock loss. Fallen rock is present on the dried, cracked mud that carpets the floor, indicating ongoing loss since the most recent flood in 1994. Gates C and D have substantial rock loss adjacent to diagonal open joints. Ceiling rock loss is present in most chambers, and includes notable quantities of post-fire losses. Severe ceiling rock collapse has occurred in chambers Cb and C, with large amounts of fallen rock lying atop the mud layer. Particularly noticeable in rear chambers D and Da, the ceiling rock is highly fragmented and many detached pieces are at risk of falling.

Areas of salt efflorescence, especially at the bases of the rear chamber walls, and salt infill in joints can be seen throughout the tomb. A continuous horizontal water line marks the walls half way up, particularly in rear chambers D and Da. Little painting survives in this tomb. The extent of surviving painting and plaster is difficult to determine due to the blackening and sediment deposit in areas. Wasp nests can also be seen throughout the tomb. Fire damage is not uniform throughout the tomb. It appears to have been localized, as some areas of the tomb were not impacted by the fire. The fire caused both blackening, heat alteration, and damage. Chamber (B) is severely blackened and probably suffers from heat alteration in upper parts of walls and ceiling. Side chambers (Ca) and (Cb) both show signs of fire damage, though chamber (Ca) has heavier blackening. Heat damage to the plaster has made surviving areas of decoration extremely fragile and has led to loss of the upper plaster layer, as seen in side chamber (Ca). The plaster is separating from the rock which has led to post-fire losses. Rear chamber (D) has fragments of painting and plaster that survive. The plaster is pink in color and appears altered by heat but not blackened.

Diagonal open joints in the clay-rich rock coupled with cyclic flood events have greatly contributed to the conditions noted in this tomb. Flooding has subjected the rock of the tomb to swelling and drying pressures, which have resulted in further fracturing and rock loss, particularly of door jambs and in ceilings, some of which has occurred since the most recent flood in 1994. The tomb continues to be immediately threatened by flooding, being adjacent to the main drainage channel, which is fed by a catchment area.

Hieroglyphs

Prince Rameses Meryamen

King's Son born of the Great Royal Wife, Greatest of Seers, Rameses-Meryamen

sA-nswt-ms-n-Hmt-wrt-nswt wr-mA.w ra-ms-sw-mry-imn

King's Son born of the Great Royal Wife, Greatest of Seers, Rameses-Meryamen

sA-nswt-ms-n-Hmt-wrt-nswt wr-mA.w ra-ms-sw-mry-imn

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

Decorating the Tombs

Bibliography

Abitz, Friedrich. Ramses III. in den Gräbern seiner Söhne (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 72). Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätverlag and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986.

Aston, D.A. The Theban West Bank from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty to the Ptolemaic Period. In: Nigel Strudwick, and John H. Taylor (Eds.). The Theban Necropolis: Past, Present and Future. London: British Museum, 2003: 138- 63.

Demas, Martha and Neville Agnew (eds). Valley of the Queens. Assessment Report. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2012, 2016. Two vols.

Grist, Jehon. The Identity of the Ramesside Queen Tyti. Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

Grist, Jehon. The Identity of the Ramesside Queen Tyti. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 71 (1985): 71-81.

Hassanein, Fathy. Étude comparative de quatre tombes de princes, fils de Ramsès III, de la Vallée des Reines. PhD diss., Lyon: Université Lumière de Lyon-II, 1978.

Hay of Linplum, Robert. Hay MSS [Robert Hay of Linplum and his artists made the drawings etc. in Egypt and Nubia between 1824-1838]. British Library Add. MSS 29812-60, 31054.

Kitchen, Kenneth A. Ramesses VII and the Twentieth Dynasty. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 58 (1972): 182-94.

Leblanc, Christian, and Alberto Siliotti. Nefertari e la valle delle regine. 2nd ed. Florence: Giunti, 2002.