QV 75

Queen Henutmire

Entryway A

See entire tombGate B

See entire tombThis gate provides access to the first chamber. It was not decorated.

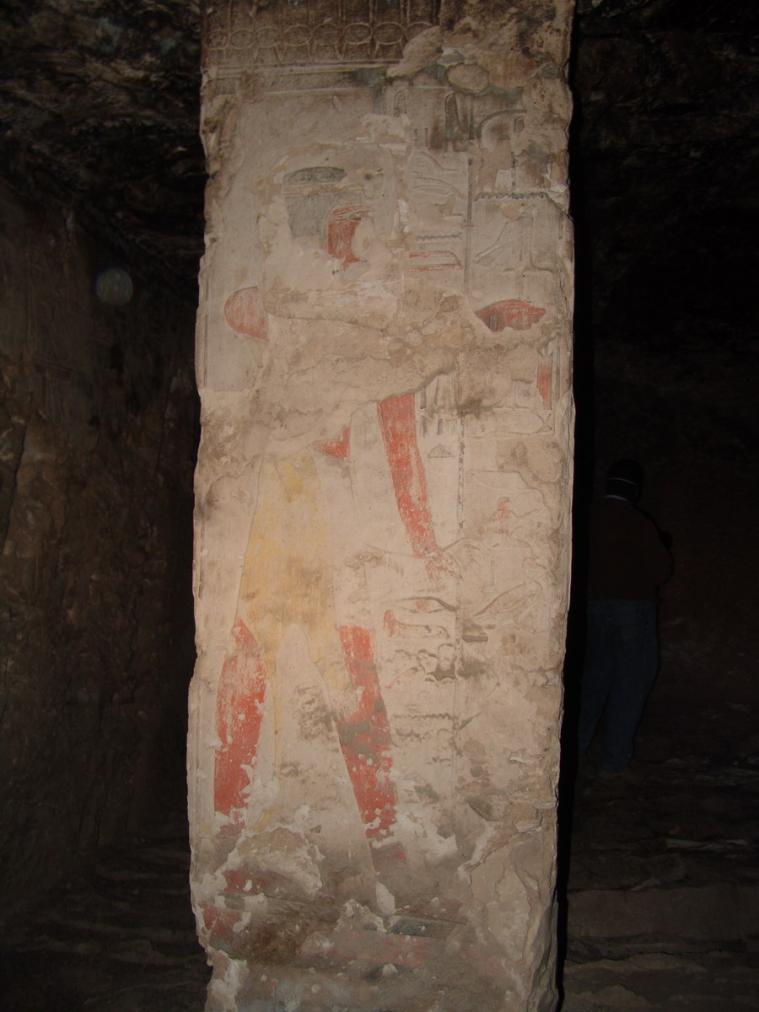

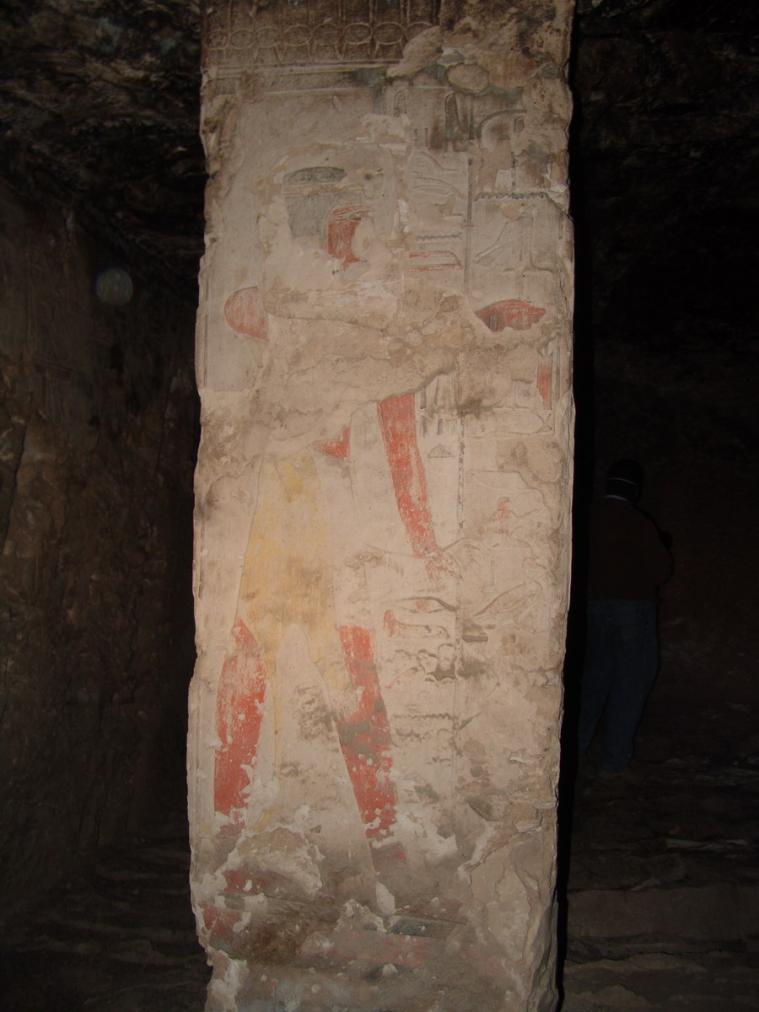

Pillared chamber B

See entire tombThis is the first chamber in the tomb and contains two pillars with decorated faces. The iconography in this chamber centers on two spells from the Book of the Dead (145 and 146), which provide the queen with protection and access through the 5th-8th gates of the underworld. She is also shown offering to several deities and receiving offerings herself.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate C

See entire tombThis gate is on axis with the entryway and provides access to a stairwell. It has no extant decoration.

Stairwell C

See entire tombThe central section of the floor of this chamber originally consisted of a steep stairway. These stairs are now badly damaged and only traces remain at the sides. The floor on the east and west sides of the chamber are level with the previous chamber. The stairwell's walls were once decorated, but no relief is visible today. The only extant decoration in this chamber remains on the upper walls and consists of the queen offering to various deities.

A pit was cut into the stairway approximately three-quarters of the way down and leads to a rough, undecorated chamber.

Porter and Moss designation:

Chamber Ca

See entire tombA pit was cut into the stairs of stairwell C approximately three-quarters of the way down and leads to a rough, undecorated chamber. This was added during a period of reuse. The Franco-Egyptian Mission excavated this chamber and discovered burial equipment dating to the Third Intermediate Period.

Chamber plan:

RectangularRelationship to main tomb axis:

PerpendicularChamber layout:

Flat floor, no pillarsFloor:

One levelCeiling:

Flat

Gate D

See entire tombThis gate lies on axis with the entryway and provides access to the pillared burial chamber. There is no extant decoration.

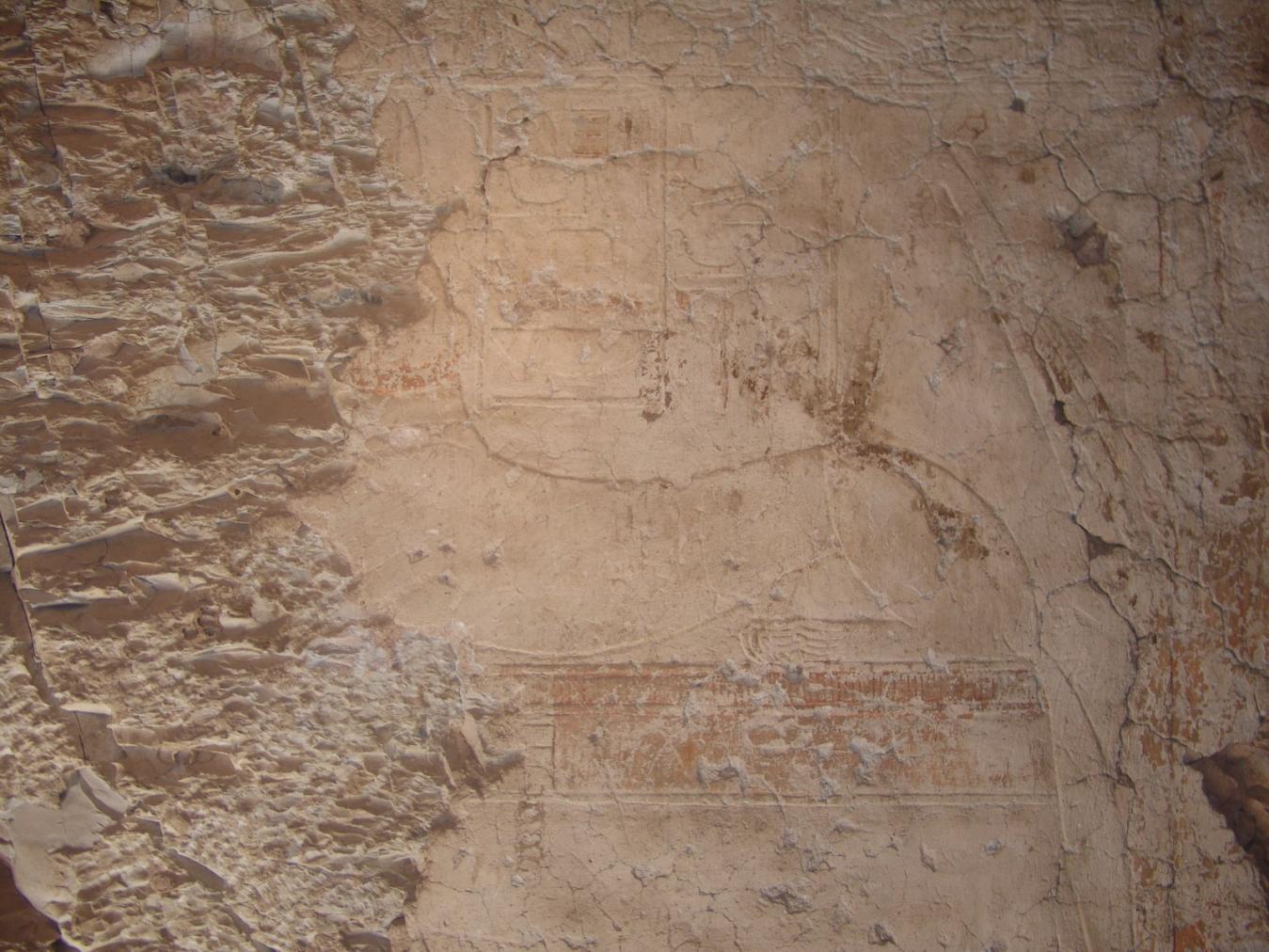

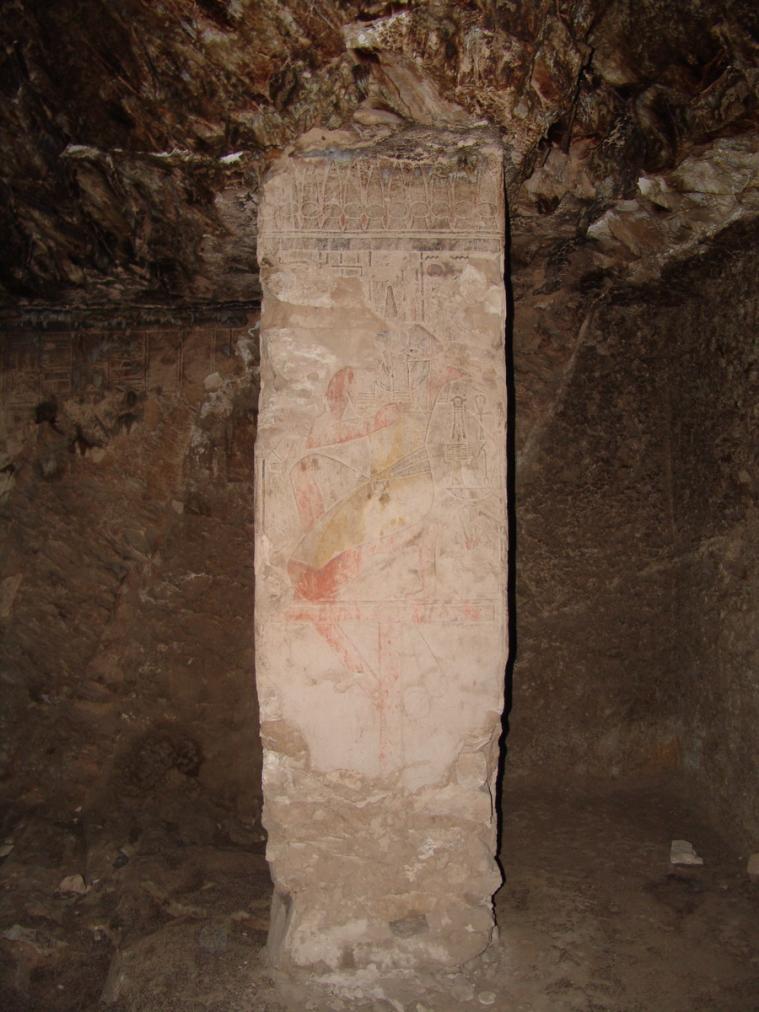

Burial chamber D

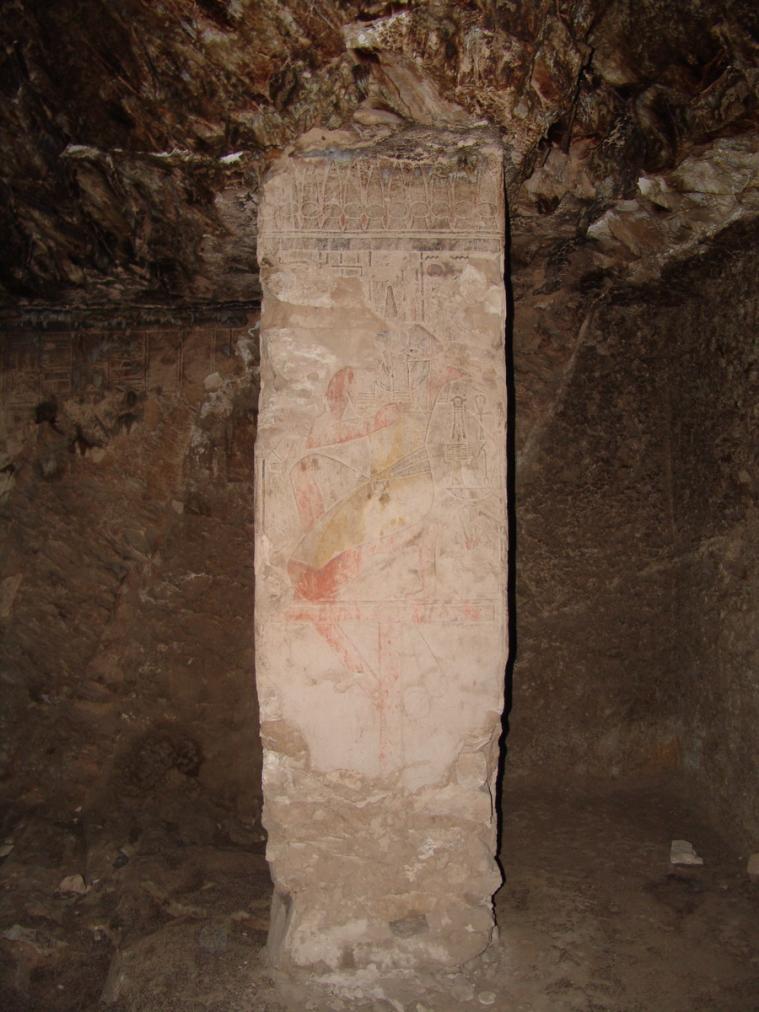

See entire tombThe burial chamber lies on axis with the tomb's entryway and originally contained four decorated pillars. The northeast pillar has since collapsed. The iconography of this chamber is indicative of its function as the resting place for the queen, and includes images of the queen's burial equipment, as well as solar and Osirian themes.

The Sarcophagus of the queen was usurped by the great priest of Amun, Harsiese, and discovered in his tomb at Madinat Habu. It is now housed in the Cairo Museum (JE 60137).

Chamber plan:

RectangularRelationship to main tomb axis:

ParallelChamber layout:

Flat floor, pillarsFloor:

One levelCeiling:

Flat

Porter and Moss designation:

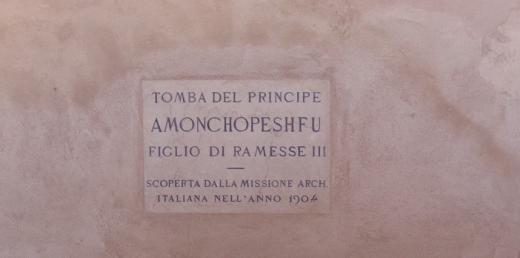

About

About

QV 75 is situated on the north side of the main Wadi amongst other 19th Dynasty tombs. The tomb is entered through a short Ramp (A), once stepped, leading into chamber (B) with two constructed pillars remaining. A short, small stairwell (C) that contains a deep vertical shaft leading to a small lower side chamber (Ca) leads down into the burial chamber (D). The burial chamber originally contained four masonry constructed pillars and the northeast one has collapsed. Remains of a later small stone structure, possibly a wall, survive in the southwest corner of this room. Generally, the interior rock quality is good, which allowed the tomb walls to be cut fairly straight. However, infilling with rock shards and plaster was still needed in localized areas. The tomb floor is roughly cut and appears to be unfinished.

QV 75 is attributed to Henutmire ("Mistress who is Like Re"), who was the daughter of Rameses Il and an unknown queen. Some scholars suggest, however, that she was a daughter of Seti I and Tuy (QV 80), since the image of Henutmire is carved next to Tuy with the titles 'daughter of the king' and 'King's wife' on a statue housed in the Vatican. This is contrary to that suggested by Hourig Sourouzian and Christian Leblanc, who believe that she is the daughter of Ramses II, as the Vatican statue was almost certainly made during the reign of Rameses II. Henutmire’s tomb was plundered in the late 20th Dynasty and her Coffin was reused by the great priest of Amun, Harsiese, who was buried at Madinat Habu in the 22nd Dynasty. Based on the archaeological material recovered by the Franco-Egyptian Mission, the tomb appears not only to have been reused during the 22nd Dynasty, but again during the Roman period. The undecorated pit (Ca) was excavated in stairwell C during one of these later periods of reuse. Since QV 75 is the 19th Dynasty tomb closest to the mouth of the Valley, it may have been the last tomb in the Valley of the Queens to be completed. Given the relatively high frequency of the title "daughter of the king" amongst the remaining inscriptions in the tomb, it is possible that the tomb was initially carved for a princess but was adapted for Queen Henutmire at the time of her death. Large but fragmentary areas of raised relief painting and lower plaster layers survive throughout the tomb on walls, ceiling, and remaining pillars. The paintings show evidence of severe heat-related damage but only some fire-blackening.

The tomb has been accessible at least since the time of Robert Hay of Linplum (1826), as he recorded the poor condition of the tomb and the "apparent omission of the owner's name". Elizabeth Thomas (1959-60) noted that although the wall paintings in chamber (D) suffered fire damage, they were better preserved than in chamber (B), where salts affected the painting condition more than fire. The TMP (1981) drawings record Steps on ramp (A), which are now substantially damaged and are only still preserved along the ramp sides. Most recently, the tomb was cleared by the Franco-Egyptian Mission in 1984, and again between 1986-87. Currently the tomb is not open to visitation and access is prevented by a metal door.

Noteworthy features:

QV 75 is attributed to Henutmire ("Mistress who is Like Re"), who was the daughter of Rameses Il and an unknown queen. The tomb was reused extensively in the Third Intermediate and Roman Periods.

Site History

The tomb was constructed in the 19th Dynasty. It appears to have been looted by organized plunderers in the 20th Dynasty. During the Third Intermediate Period, 22nd Dynasty, the tomb was opened and the Sarcophagus was transferred to Madinat Habu and reused by the Great Priest Harsiese. The tomb was reused once again for a short period during the 2nd to 3rd Centuries AD (Roman Period).

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

Very little previous conservation has been undertaken in this tomb. According to the GCI-SCA, only a few edging repairs are visible.

Site Condition

According to the GCI-SCA, there are no Steps extant in Ramp (A), although some plaster still survives on the ramp walls. Above the entrance are some hanging fragments of rock. The tomb interior has no apparent structural risks or signs of instability of walls or ceiling. The ceiling near the entrance doorway shows some collapse, though this appears to be historic. The west door jamb also presents rock loss and some adjacent loose fragments. The two constructed pillars in chamber (B) both survive to the ceiling with extensive remains of plaster. The ceiling has a very irregular surface and many micro-fractures in the rock, but no recent loss. On the west wall of chamber (B) there is a large area of loss. In Gates (C) and (D), the lintels and jambs have localized loss and fracturing. The ceiling in burial chamber (D) presents major historic loss in the area of the missing northeast pillar, but nothing post-fire. Some fracturing and salt veins also occur here.

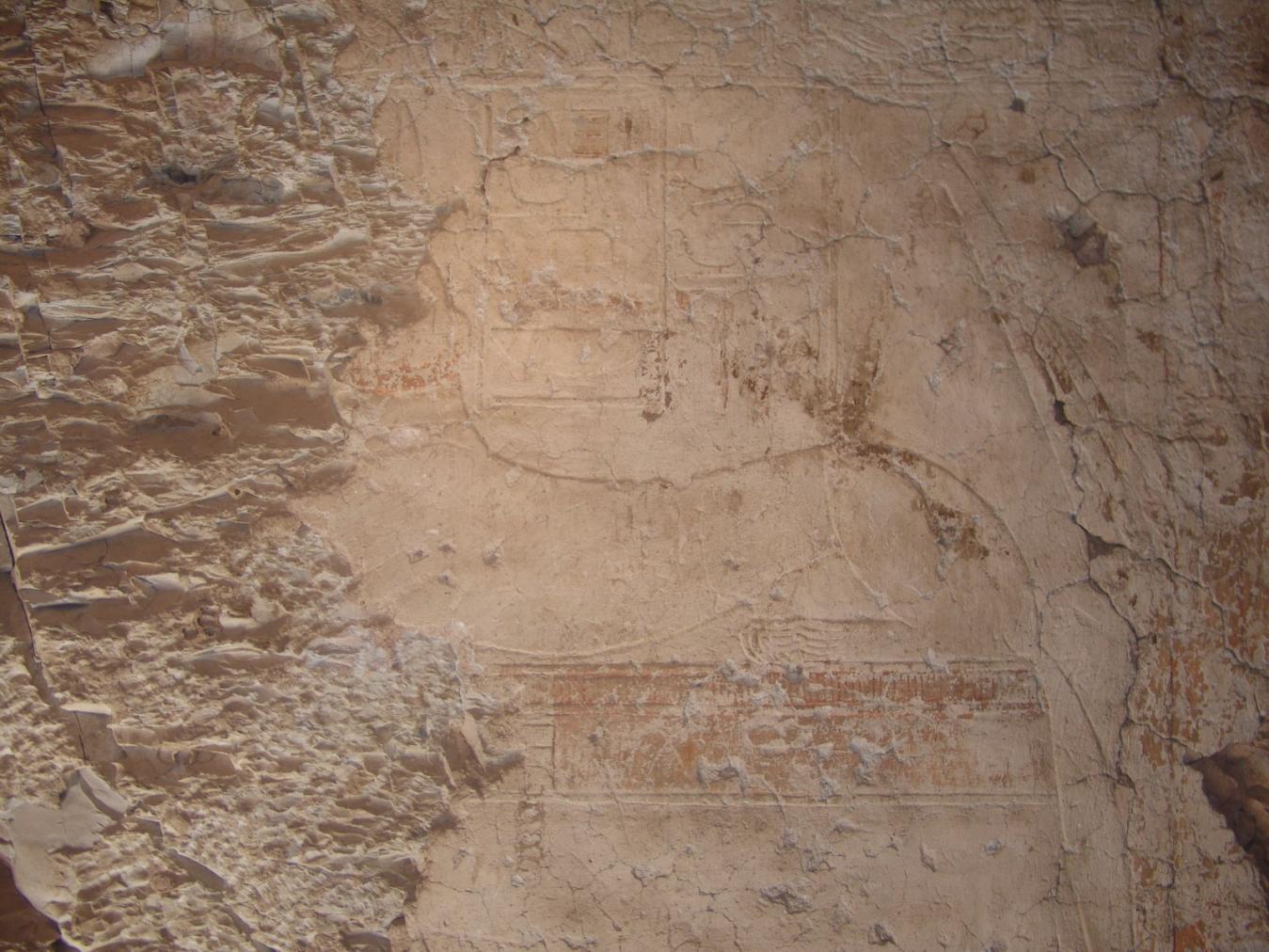

The surviving areas of painting and plaster in the tomb have suffered severe fire damage. The paintings in chamber (B) are not fire-blackened but show signs of heat damage. The plaster layer appears to have been altered and is now highly fragmented with a network of cracks that has destabilized many areas. Heat has also caused pigment alteration, which is most notable in the changes from yellow to red of the iron oxide pigments. These are the most prominent surviving colors, though faint traces of green can be seen in more protected areas. The painted surface is rough in appearance and has suffered loss. In some areas the paint layer is almost entirely gone leaving only the unpainted raised relief plaster behind. The condition of the decoration in stairwell (C) is similar, though plaster and painting looks even more severely heat altered with a red-hued appearance. Three of the four constructed pillars in the burial chamber (D) survive. The northeast pillar (rear, right pillar) has been lost. The remaining pillars have good survival of painted plaster. The ceiling has losses, but all are fire-blackened, indicating that no post-fire losses have occurred. However, despite the blackening, there is less heat alteration in the burial chamber (D) with areas of unaltered yellow paint remaining on pillars and walls and less cracking of the plaster as compared with other parts of the tomb. The rear wall of the burial chamber has salt accretions and there is almost no surviving decoration on this wall. There is evidence of localized attempts of theft of areas of painting. A combination of factors have contributed to the fracturing and loss of rock in the tomb, including the heavily jointed and fractured marl of the tilted block and its proximity to the top of a ridge, and the presence of salt veins. The tomb has had extensive bat activity with crystalline deposits on the surface of the wall paintings and droppings found throughout. Bats were also noted during the February 2008 GCI-SCA inspection. Bird droppings were also noted on a pillar in the burial chamber, as well as insect nests found throughout the tomb.

Hieroglyphs

Queen Henutmire

King's daughter of his body, his beloved, the Great Royal Wife, Lady of the Two Lands, Mistress who is like Re

sAt-nswt-n-Xt.f mr.f Hmt-wrt-nswt nbt-tAwy Hnwt-mi-ra

King's daughter of his body, his beloved, the Great Royal Wife, Lady of the Two Lands, Mistress who is like Re

sAt-nswt-n-Xt.f mr.f Hmt-wrt-nswt nbt-tAwy Hnwt-mi-ra

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

Decorating the Tombs

Bibliography

Champollion, Jean-François. Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie. Vol. 1-2. Paris: Firmin-Didot Frères; Geneva: Editions de belles-lettres, 1845.

Demas, Martha and Neville Agnew (eds). Valley of the Queens. Assessment Report. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2012, 2016. Two vols.

Dodson, Aidan and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Hay of Linplum, Robert. Hay MSS [Robert Hay of Linplum and his artists made the drawings etc. in Egypt and Nubia between 1824-1838]. British Library Add. MSS 29812-60, 31054.

Leblanc, Christian, and Alberto Siliotti. Nefertari e la valle delle regine. 2nd ed. Florence: Giunti, 2002.

Leblanc, Christian. Architecture et évolution chronologique des tombes de la Vallée des Reines. Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire 89 (1989): 227-247.

Leblanc, Christian. L'identification de la tombe de Henout-mi-rê: fille de Ramsès II et grande épouse royale. Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire 88 (1988): 131-46.

Leblanc, Christian. Ta set nefrou: une nécropole de Thèbes-ouest et son histoire, 1: géographie- toponymie: historique de l'exploration scientifique du site. Cairo: Nubar Printing House, 1989.

Leblanc, Christian. TA st nfrw: une nécropole et son histoire. In: Sylvia Schoske (ed.), Akten des vierten Internationalen Ägyptologen Kongresses: München 1985, International Congress of Egyptologists (4th: 1985: Münich, Germany) II: 89-99. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. Beihefte I. Hamburg, 1988.