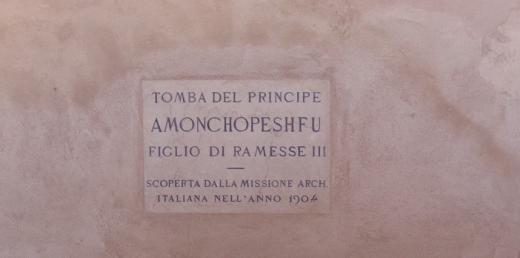

QV 42

Queen Minefer & Prince Pareherunemef

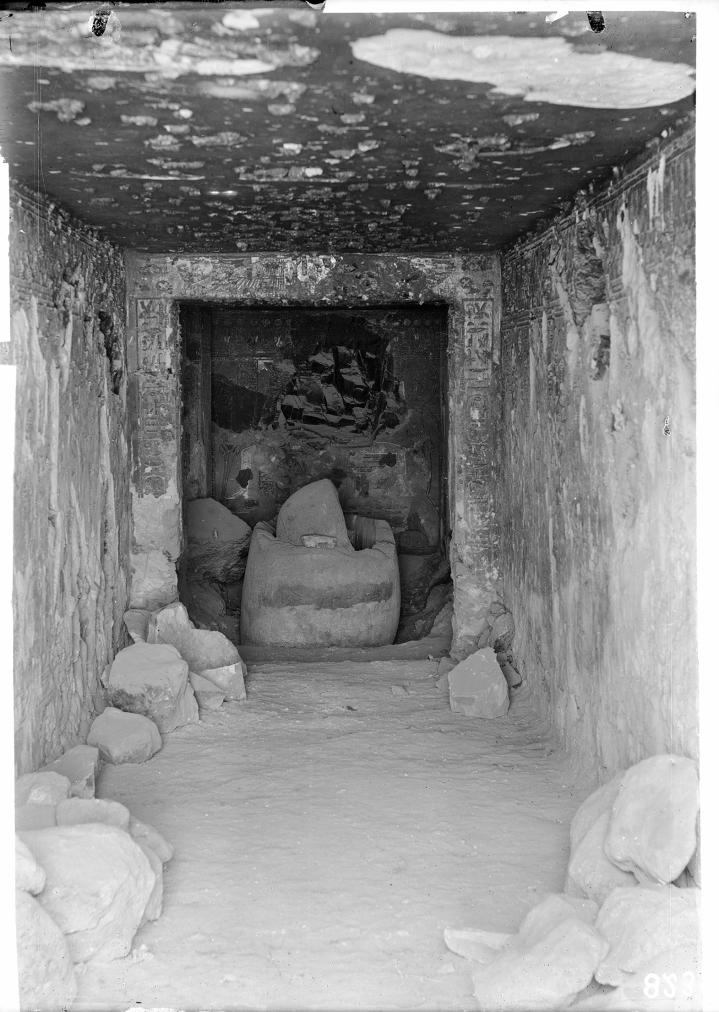

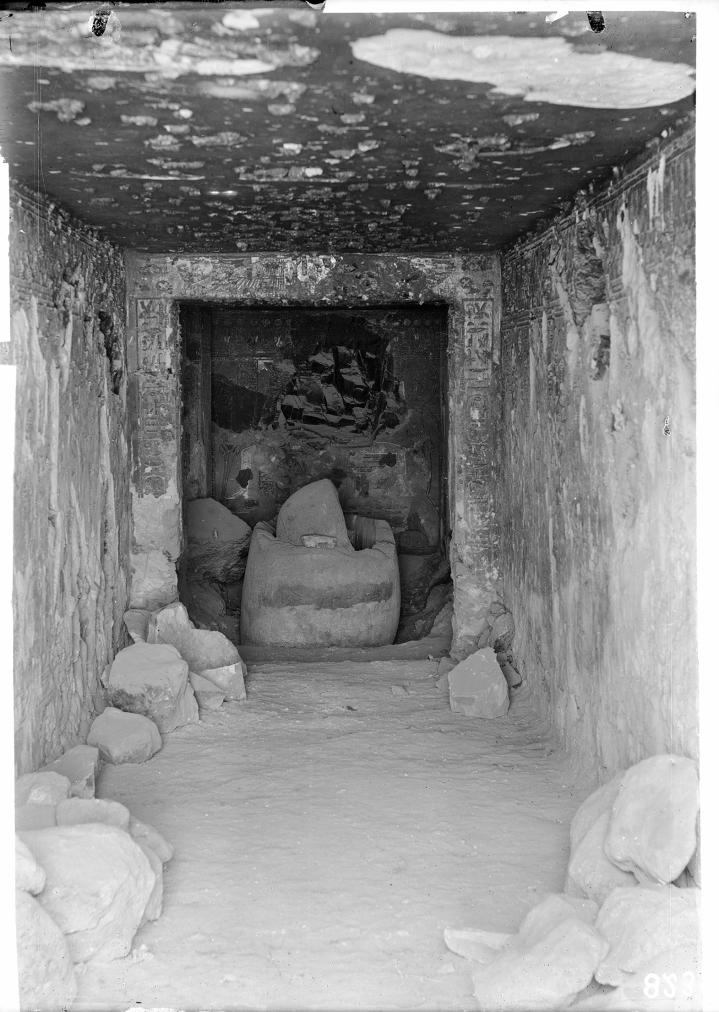

Entryway A

See entire tomb

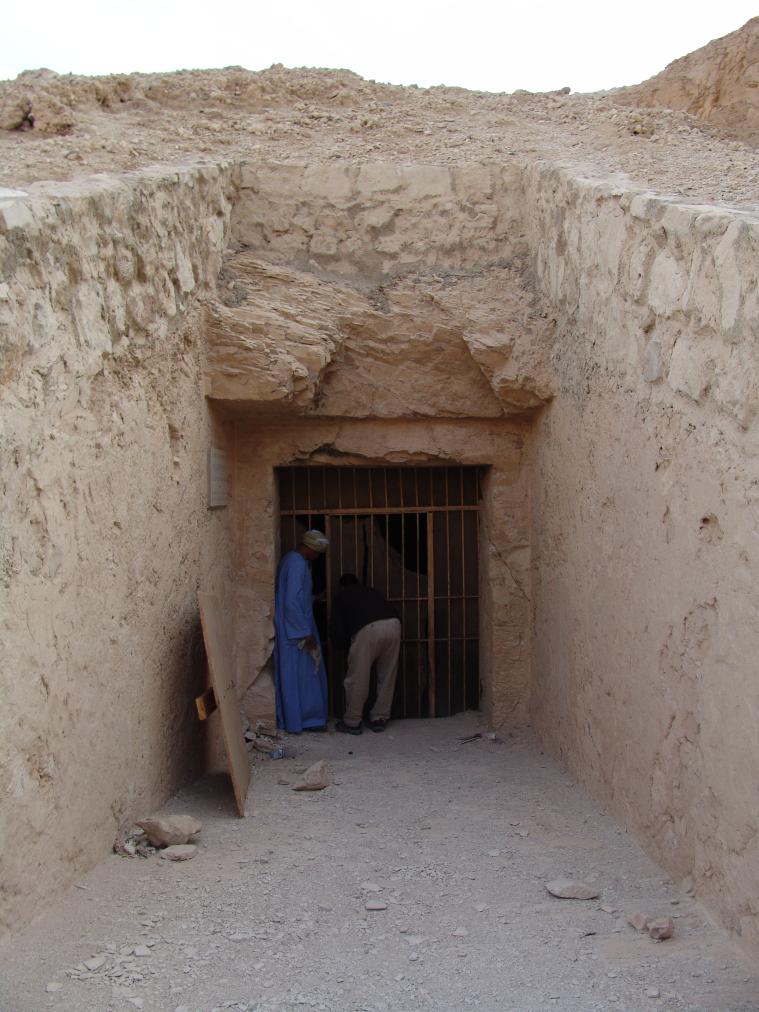

Gate B

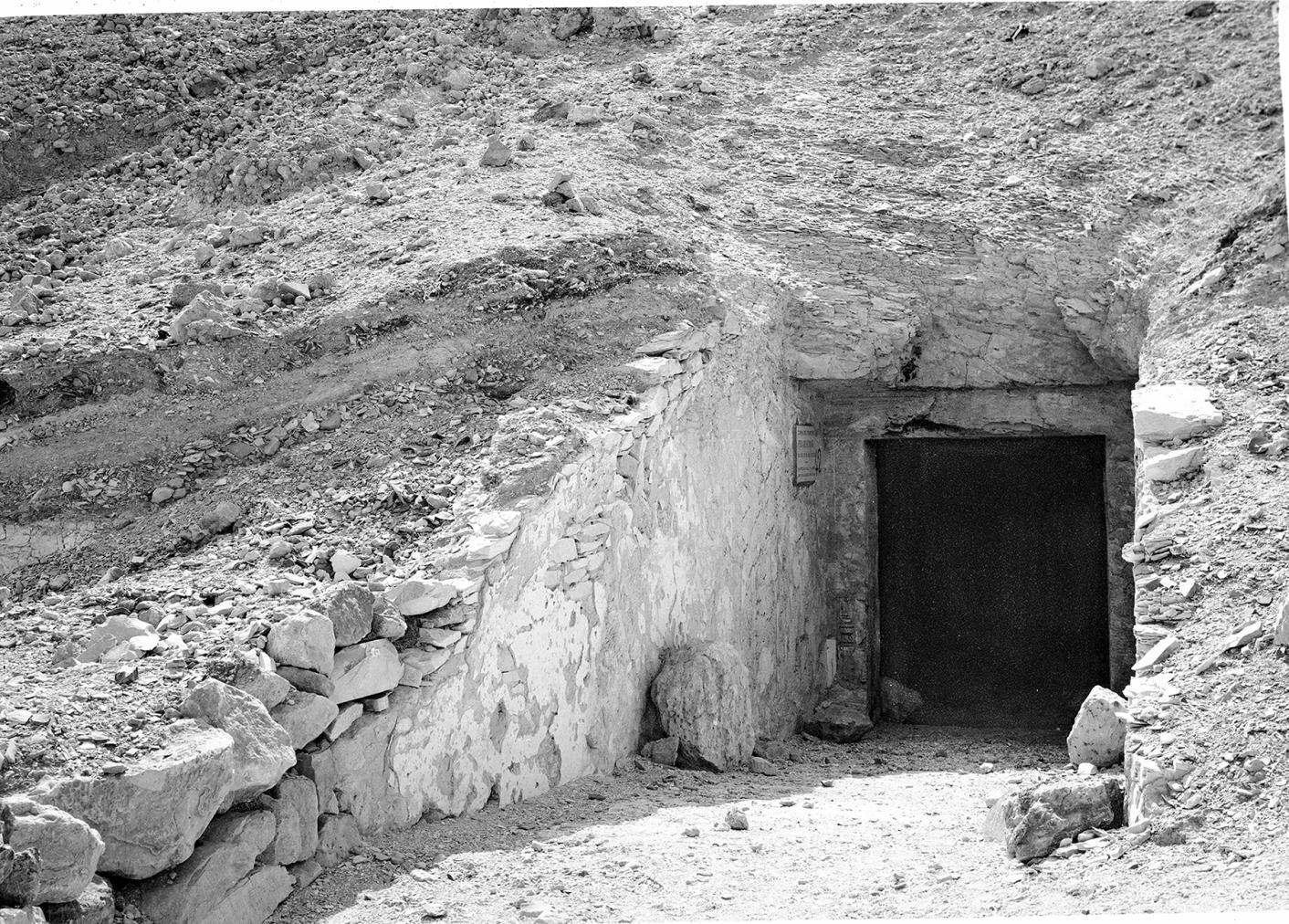

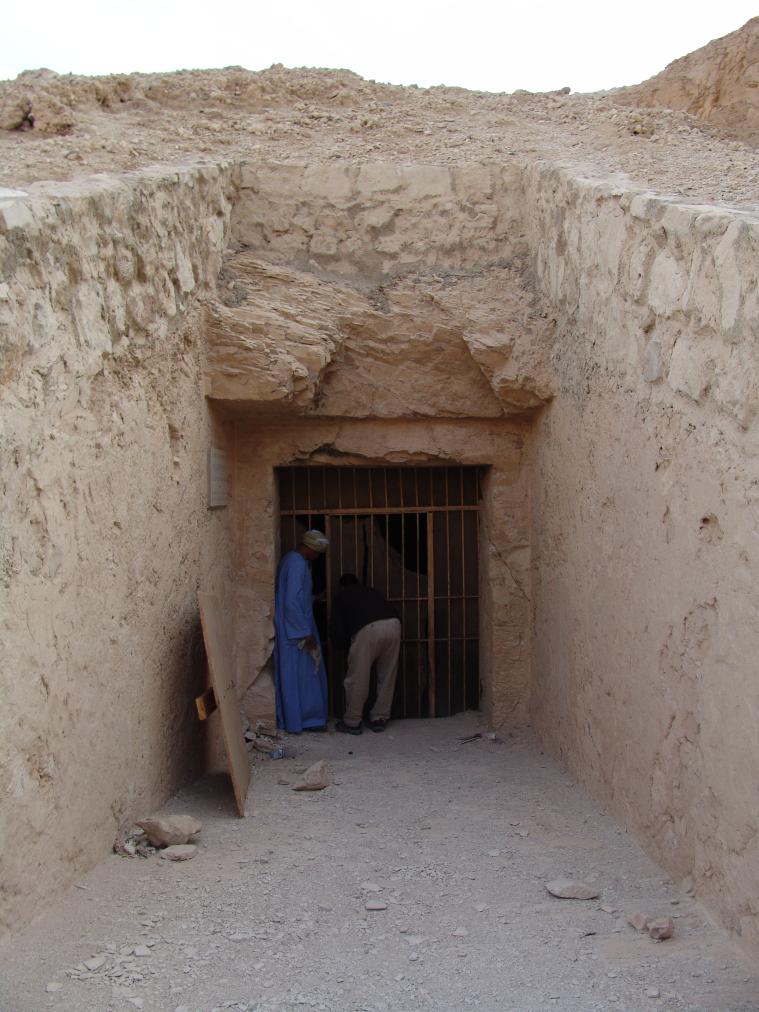

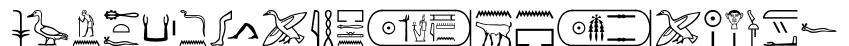

See entire tombThis gate provides access to the first corridor of the tomb. The only decoration that has survived is on the left reveal and consists of text. A Hieratic graffiti was noted here by Elizabeth Thomas. Currently the tomb is not open to visitation and a metal grill door with failing wire mesh prevents access.

Porter and Moss designation:

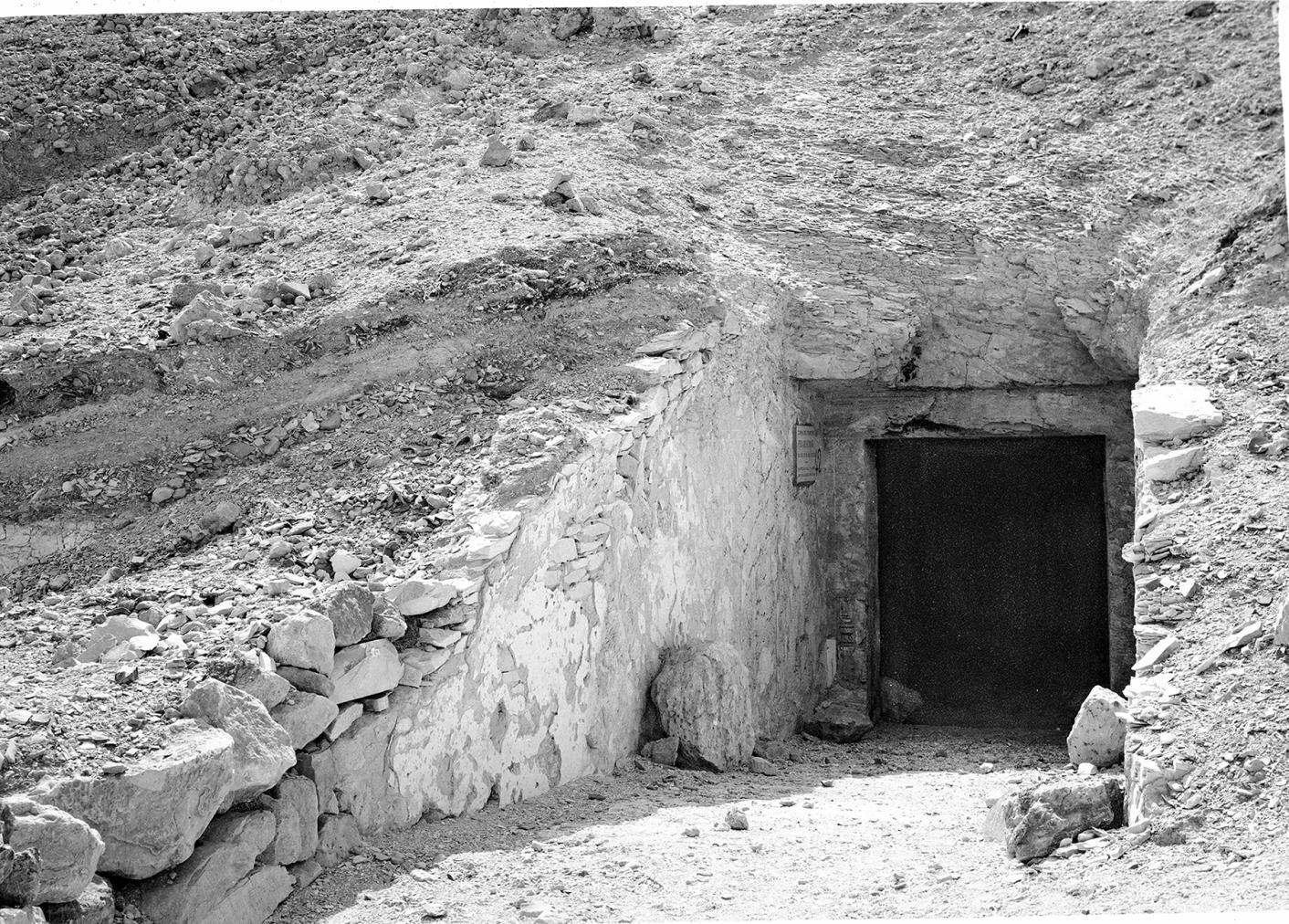

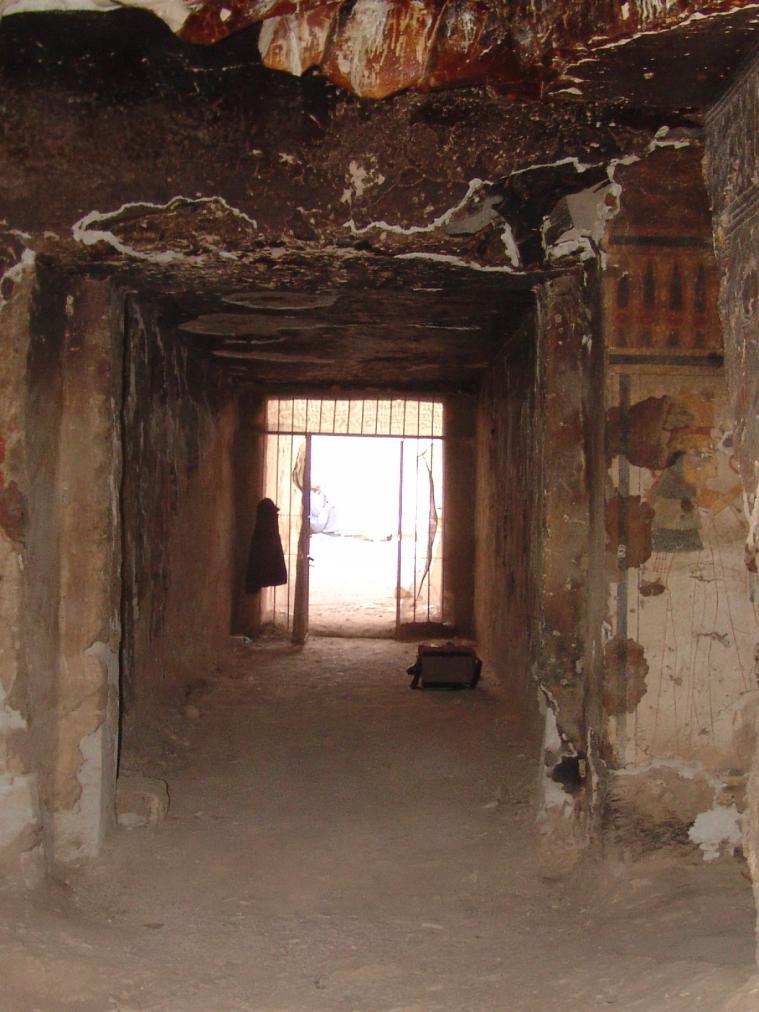

Corridor B

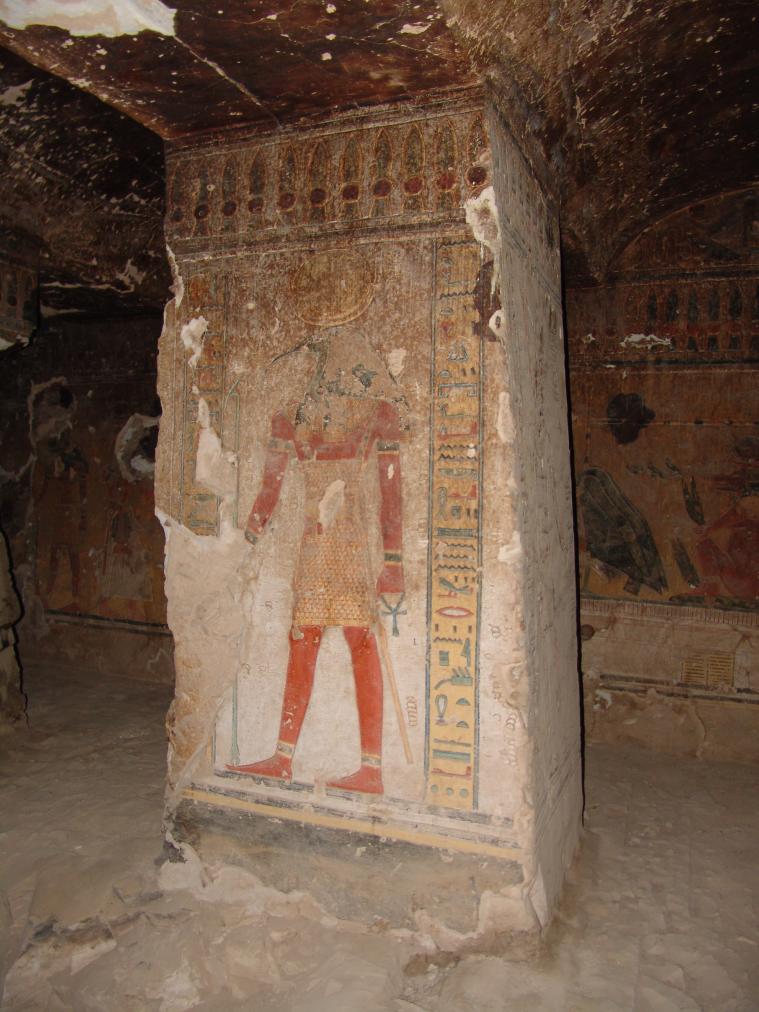

See entire tombThis corridor lies on axis with the tomb entrance and is decorated with painted sunken relief. As with the other sons of Rameses III, the king is shown as the dominant figure in the scenes and interacts with the deities on behalf of his son. The Prince is shown with the side lock of youth and carries a plume. The iconography centers on the king and the prince offering to and adoring various deities, including Ptah, Meretseger, Geb, and Osiris.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate C

See entire tombThis gate provides access from the corridor to the burial chamber. Post holes in the floor on either side of the doorway indicate that this gate would have been closed by wooden double doors. The lintel is decorated with a winged sun disk, the reveals with texts, and the thicknesses contain a hymn.

Porter and Moss designation:

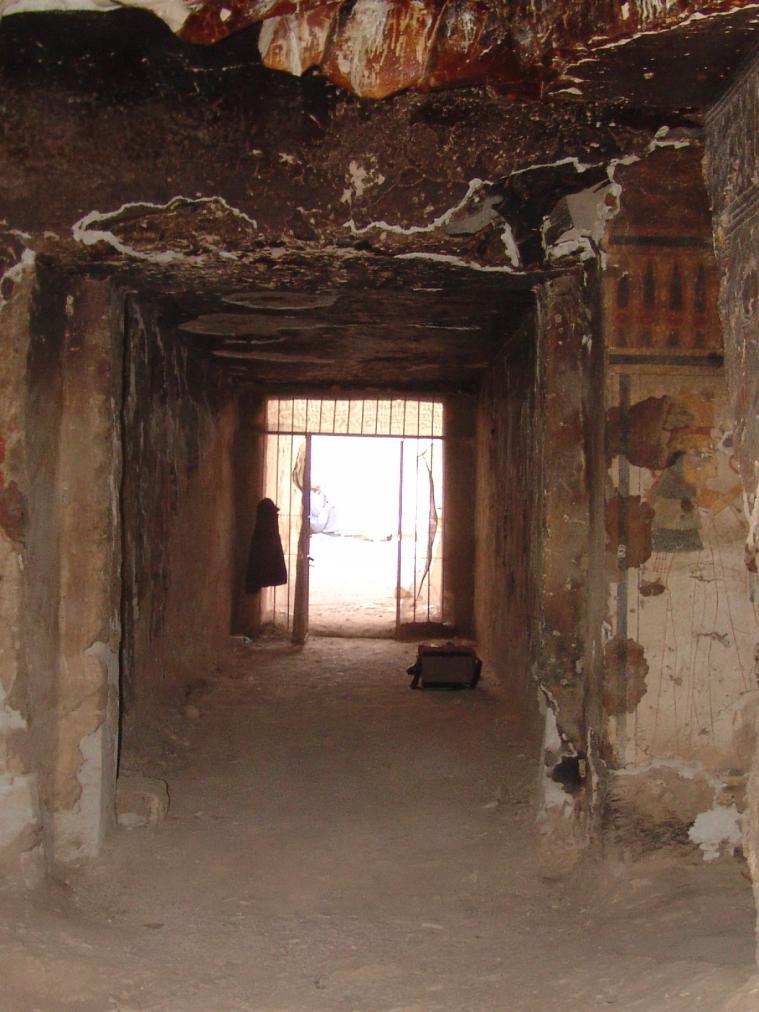

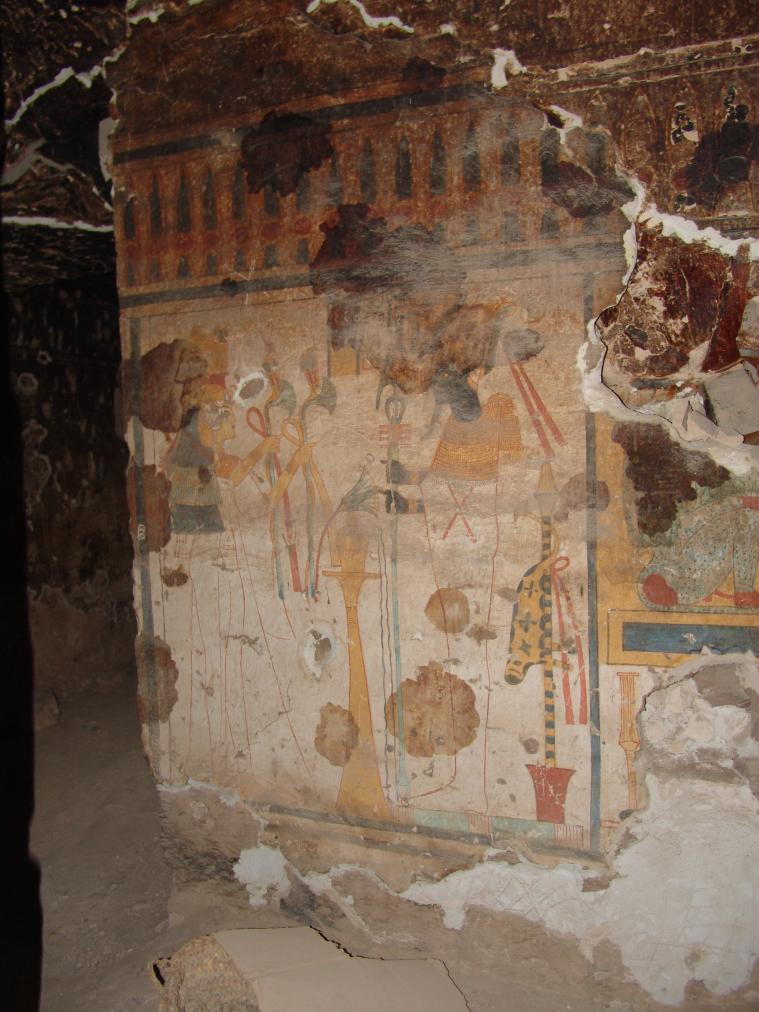

Burial chamber C

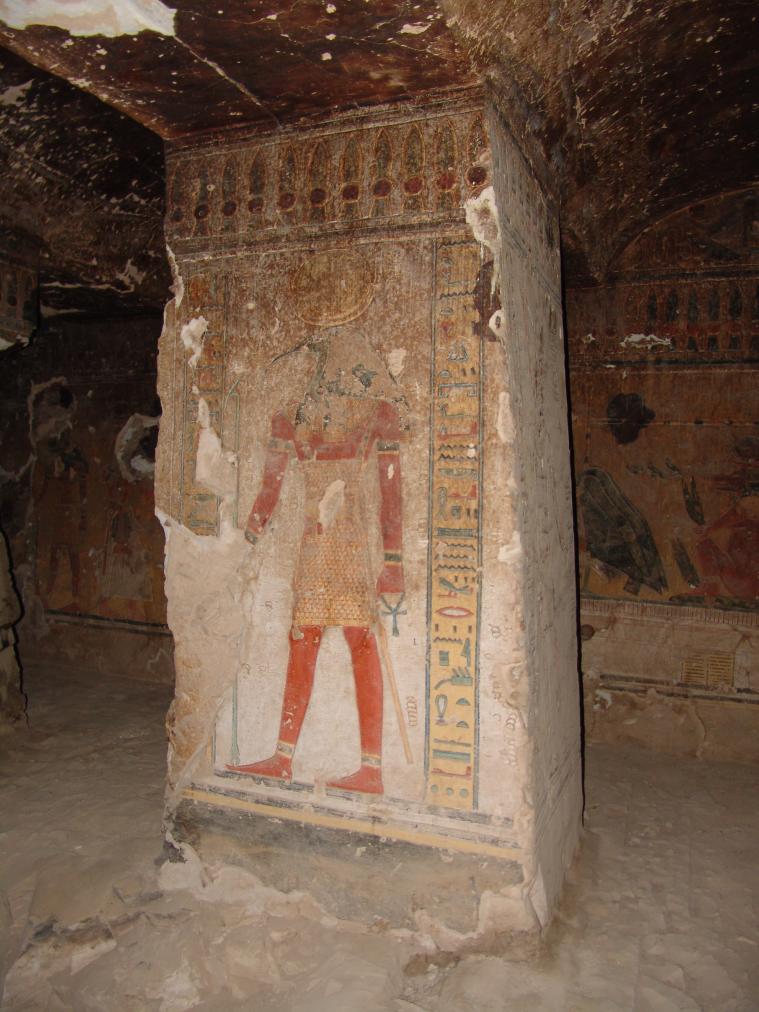

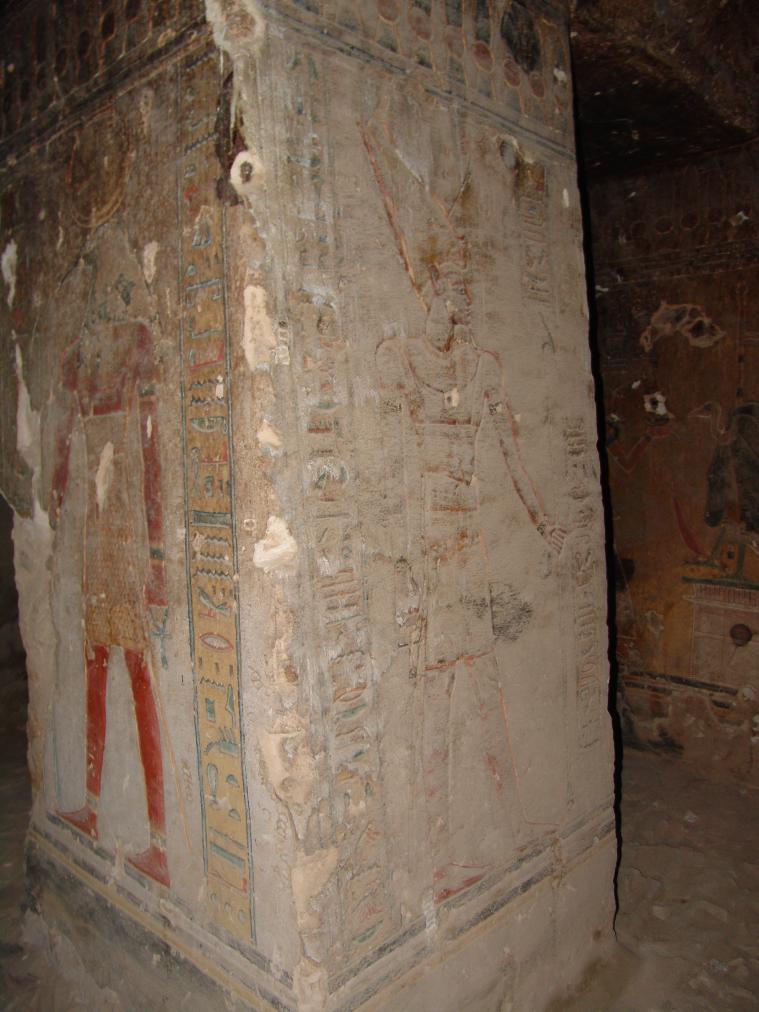

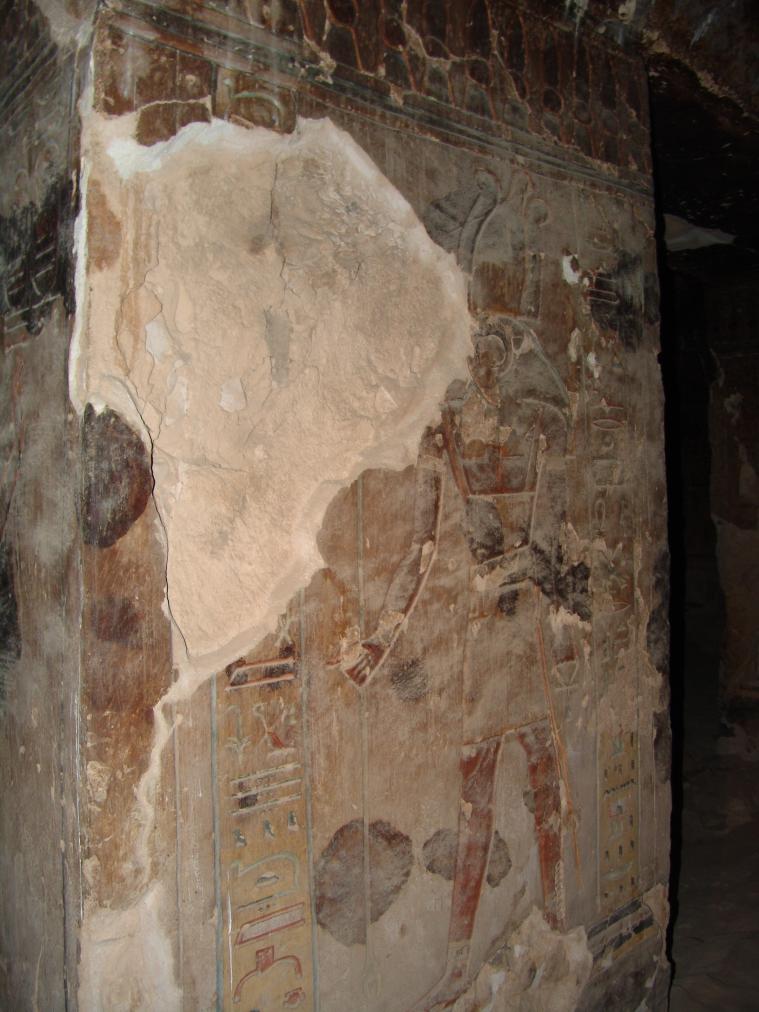

See entire tombThis chamber lies on axis with the tomb's entrance. There are four decorated pillars and the ceiling contains three barrel vaults running east-west between the pillars. A roughly-cut pit in the middle of the floor was used for the placement of the Sarcophagus. A roughly-cut niche is also present in the southern wall and is possibly of a early Christian date.

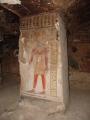

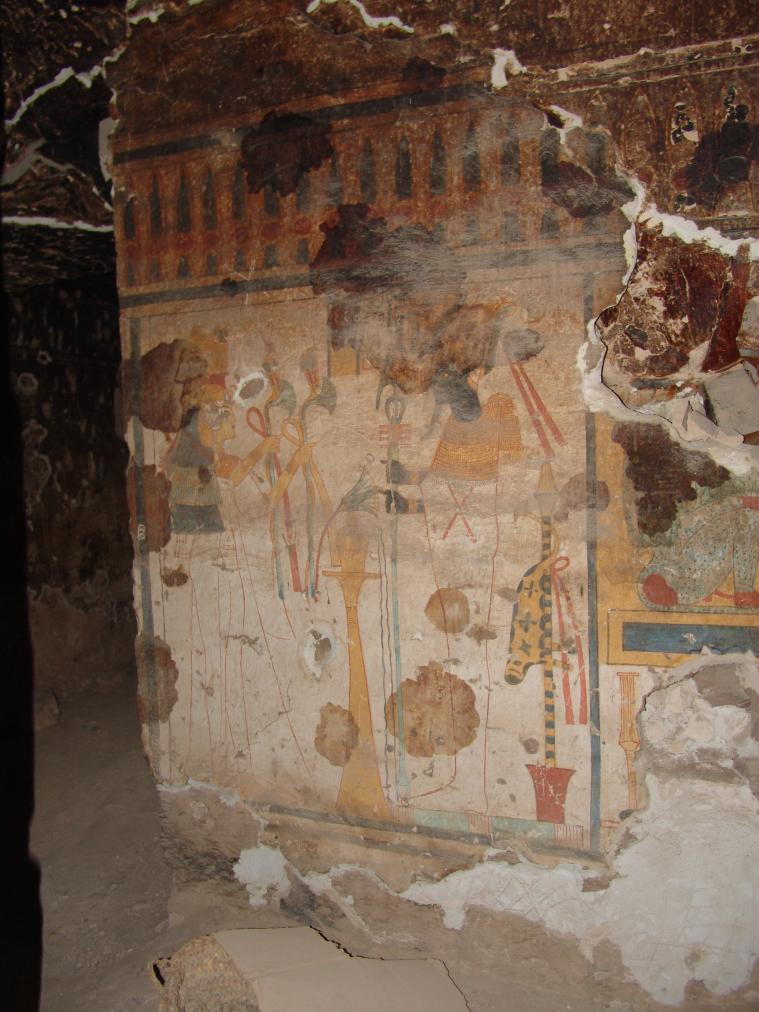

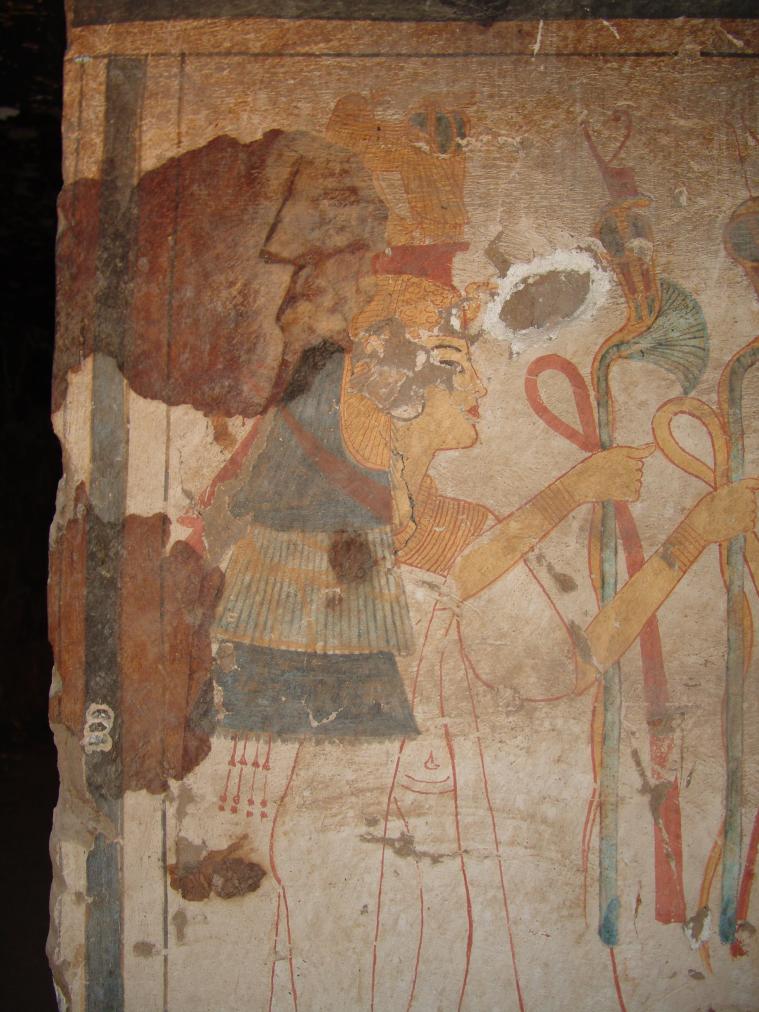

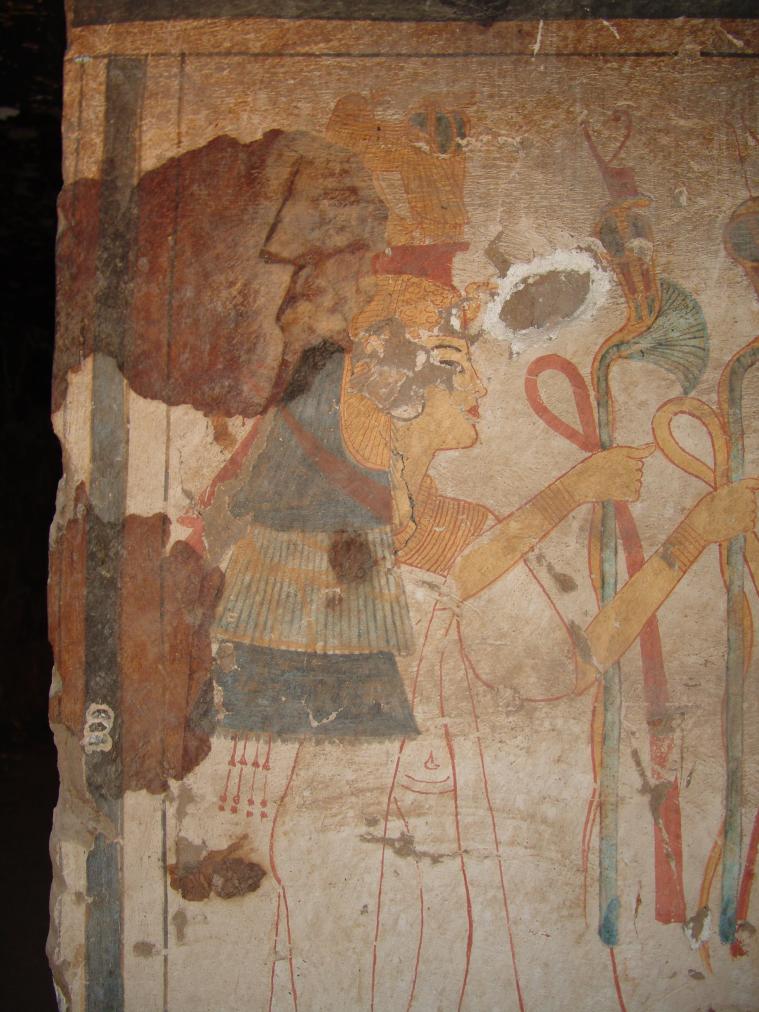

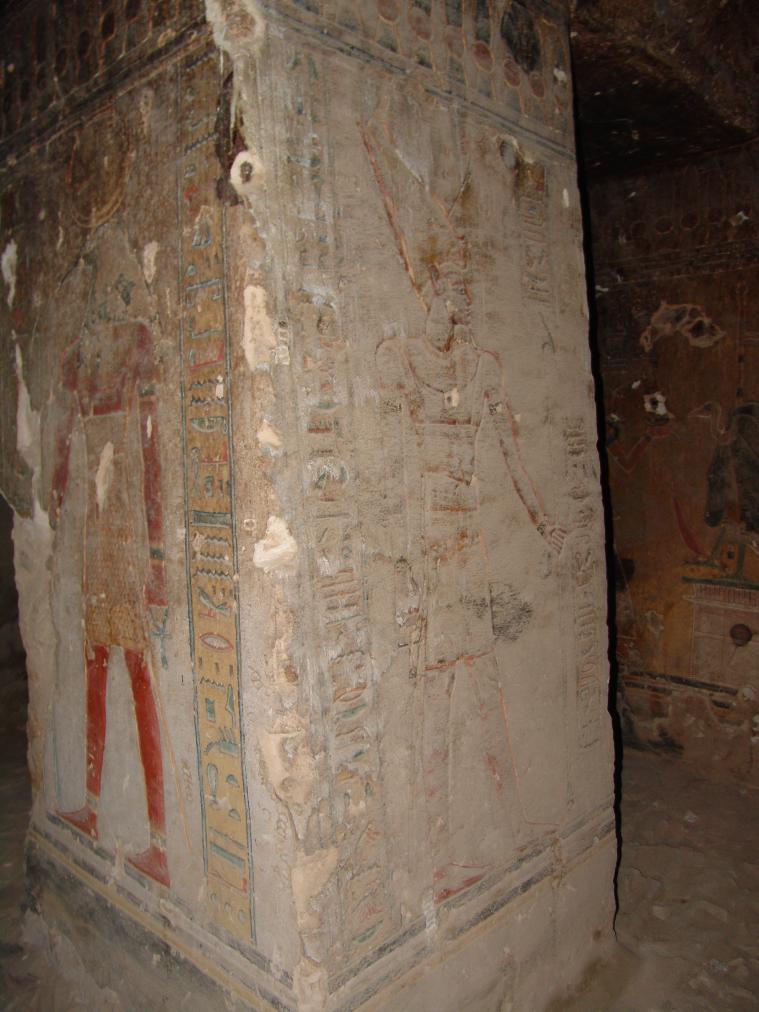

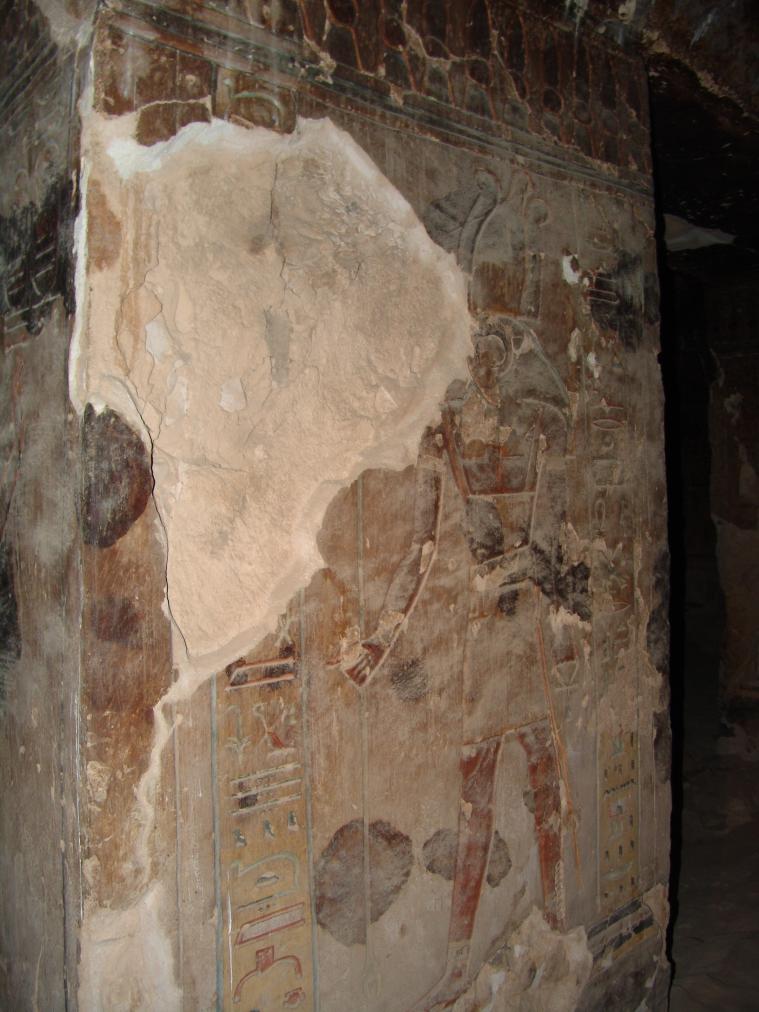

The decoration on the walls and pillars consists of painted sunken relief. The northeastern and southwestern pillars are partially intact and have images of the king offering to various deities. The other two pillars have suffered more damage, in particular the northwestern pillar. An exception to the painted sunken relief occurs on the north wall, right side. Here is a scene showing an unidentified queen offering to Osiris. This scene is not carved in relief, but is painted onto a plaster base on a wall that is constructed of mud brick. The scene is not finished, as the lower half of the queen and Osiris is depicted in red draft lines, while the upper portion of their bodies have been painted.

The iconography in this chamber centers on the protection and transformation of the deceased. As with the corridor scenes, the king is dominant and interacts with the deities on the prince's behalf. The Book of the Dead Spells 145-46 are alluded to on the east and west walls through images of the guardians, but the texts were not included. The main scene occurs on the southern wall and is a double-scene of the King and the Prince in adoration before Osiris and two female deities (Serqet and Nephthys on the right and two largely destroyed figures, probably Isis and Neit on the left).

Chamber plan:

SquareRelationship to main tomb axis:

ParallelChamber layout:

Flat floor, pillarsFloor:

One levelCeiling:

Vaulted

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Ca

See entire tombThis gate is cut into the western wall of the burial chamber and provides access to a side chamber. The decoration consists of unpainted sunken relief, indicating that it was unfinished. This is further confirmed by the fact that the side chamber is undecorated.

The lintel was carved with a winged sun disk, the reveals contain titles, and the thicknesses were decorated with a Soul of Pe (left) and Soul of Nekhen (right) kneeling on a standard.

Side chamber Ca

See entire tombThis side chamber lies to the west of the burial chamber. The chamber is well carved and the walls were carefully leveled, but no decoration was ever added.

About

About

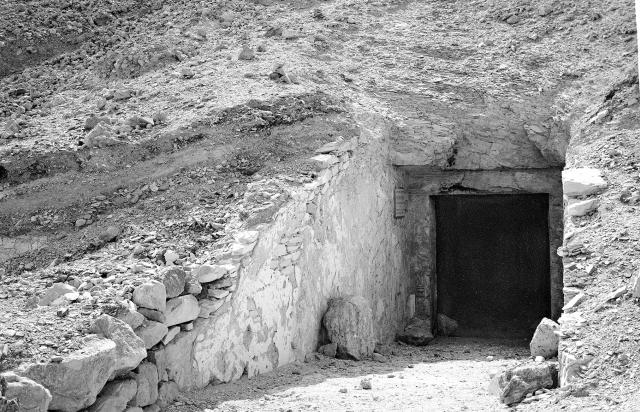

QV 42 is located at the end of the southwest branch of the main Wadi, adjacent to the main pathway. The tomb is multichambered - entered through Ramp (A), which leads into long corridor (B) and into the pillared burial chamber (C) with central sunken floor and three-barrel vaults running perpendicular to axis. A niche is present in the middle of the south wall of the burial chamber and a side chamber (Ca) is located to the west, off the burial chamber. This is the only tomb of the 20th Dynasty that has a pillared hall, with barrel vaults (the burial Chamber C). The sunken space in the floor of the burial chamber (C) likely held the Sarcophagus, as fragments of a granite sarcophagus were found by Ernesto Schiaparelli and currently reside in the Turin Museum. Erasure of the cartouches on the sarcophagus suggest the tomb was re-used.

According to Elizabeth Thomas (1959-60), the tomb may have originally been built for Minefer or another queen and started at the end of the 19th Dynasty, but was clearly usurped by Pareherunemef. Pareherunemef is the son of Rameses Ill by an unknown queen, although it is suggested that his mother was the queen Minefer from inscriptions on ushabtis found in a re-excavation of QV 42 in 1990-1 and in front of QV 45. He is number 5 on the list of sons at Madinat Habu and was possibly deceased by year 12 of the reign of Rameses III, although Christian Leblanc maintains that this dating put forward by Kenneth Kitchen and adopted by Pierre Grandet is not convincing as it uses only a particular writing of the cartouches of Rameses Ill as evidence. However, the prince did not die as a child, as one of his titles is 'Charioteer of the Stable of the Great House,' which is likely not simply honorific, but functional as well. He also held the title 'eldest king's son of his body', indicating that when he died, he was the eldest living son. Apart from his appearance as the fifth figure in the Madinat Habu prince list, he does not have any other attestations. Likewise, there are no other sources for his mother, Minefer, who was given the title 'king's mother' (mwt nswt) on one of her ushabtis. The quality of painted reliefs in QV 42 is high, although now blackened from later re-use. A different painting technique (painted plaster) is used for the depiction of the unnamed queen. An extensive amount of sunken relief painted plaster survives throughout the tomb. Areas without decoration include side chamber (Ca) and the inner face of Gate C, which were plastered but not painted, and the inner face of gate (Ca), which has carved plaster that was not painted.

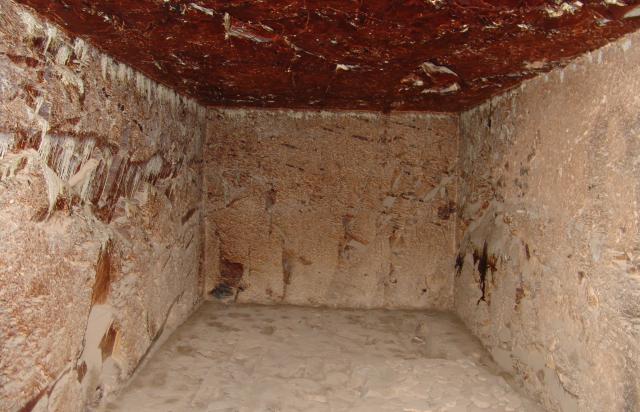

Unlike many of the 19th dynasty tombs on the south side of the main wadi, the rock is in relatively good condition. The rock walls and ceilings of this tomb were cut relatively straight and flat. Only localized areas of rock voids and collapse contemporary with original construction required infill with stone shards and large amounts of plaster to create a flat surface for the painting. Generally two plaster layers were applied, the thickness depending on the quality of the underlying rock. In a few areas, where the rock was in particularly poor condition, instead of using infill material, walls were constructed with stone or mud brick in order to create a flat vertical surface. The east side of the north wall of the burial chamber (C) has been almost entirely constructed from mud brick. The painting technique differs in this area with no relief work and a slightly cruder painting style.

The tomb has been accessible since the time of Robert Hay of Linplum (1826) and is included in subsequent visitor records. According to Elizabeth Thomas (1959-60), the tomb is the oldest of the 20th dynasty tombs and the last to appear in the Valley with pillars. It was probably usurped by Rameses Ill as a tomb for his son, though originally meant for a queen. The early death of the prince may explain the few unfinished aspects of his tomb and its closer comparison with the 19th Dynasty tombs of the wives of Rameses I with their pillared burial chambers. Thomas suggests that the different technique for the sole painted scene with the queen may have been due to a lack of time, although observation suggests this may instead be due to the reconstructed wall behind. Thomas also notes the presence of Hieratic graffiti on the left wall of corridor (B) and suggests that the niche to the rear of the burial chamber (C) was added later. Currently, the tomb is not open to visitation and a metal door prevents access.

Noteworthy features:

This is the only tomb of the 20th Dynasty that has a pillared burial chamber with barrel vaults.

Site History

The tomb was constructed in the 19th Dynasty for an unknown queen and then usurped in the 20th Dynasty for Pareherunemef. The tomb was subsequently pillaged and possibly reused, as evidenced by fire damage and blackening of the walls and ceiling throughout the tomb.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

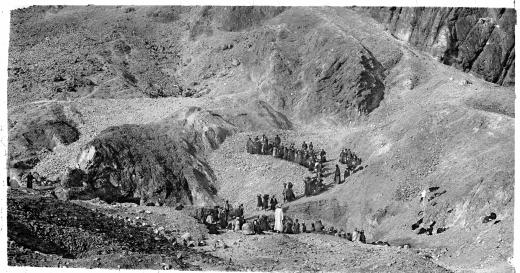

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

According to the GCI-SCA, a preliminary attempt to stabilize the rock and paintings was made in the burial chamber in 1988-90 by the Franco-Egyptian Mission. This consisted of rock infill with mortar to support the unstable rock of one of the pillars and reattach one of the fragments. Further testing was carried out in 1989 and 1991 with lime injections, edging repairs for wall painting stabilization, and cleaning using a dusting tool. Samples were taken as part of this conservation work for identification of pigments, plaster stratigraphy, minerological and petrographical characterization, and color alteration. The treatment was not comprehensive and it appears to not have been completed. The large mortar fills around the base of the walls were scored in preparation for a final finishing layer of plaster, but this was not carried out. Evidence of other localized treatments is also visible, including hemp-like fibers dipped in adhesive and placed in a rock fracture in the remaining core of one of the pillars in an attempt to hold the two pieces together; grout holes and drip marks on the surface of the paintings; and a small cleaning test on the west wall of the burial chamber. Chalk marks are visible on the east side of barrel vaults in the burial chamber and are associated with recent archaeological and/or conservation efforts.

Site Condition

According to the GCI-SCA, the two northern pillars of the burial chamber (C) have suffered substantial rock loss and associated decoration loss. Rock loss continues up to the ceiling where post-fire loss is evident and detached fragments are at risk of falling. The steeply dipping joints in the rock appear to have been a problem during the original excavation of the tomb, as there are many areas where infill masonry was used in construction of pillars. There has also been partial collapse of original sections of masonry infill, including on the south wall of the burial chamber (C), though this may have occurred in antiquity. The east side of the north wall of the burial chamber has a large diagonal crack. The plaster is in good condition, but the wall (which is constructed out of mud brick) is hollow behind and filled with debris.

There are both pre- and post-fire losses in the painted plaster. Most of the losses occur in areas where substantial infill material was used to fill voids and pockets in the rock. Post-fire losses of the paint layer can be seen on the south wall of the burial chamber including primarily on greens and blues, where areas of flaking are visible. A CNRS mission report (1988-90) records the overall condition of the tomb, mentioning notably poor adhesion of original plaster fills and the soiling of the paint layer by dust, soot, brownish stains from bat excrement, and spotting. There is extensive blackening of upper walls and ceilings of corridor (B), which lessens toward the entrance. In general, the blackening is moderate in the rest of the tomb as the color and iconography of the paintings are still largely visible. There is peculiar fire damage in side chamber (Ca), quite different from deposits found elsewhere in the tomb, similar to that found in QV 43 and QV 78. Large stains, possibly from bat activity, have darkened the painting in areas and white accretions from bat urine are concentrated on the ceiling of the burial chamber. Scratch marks, thought to be from animal activity, are found in the lower southwest corner. There are still traces of hundreds of insect nests throughout the tomb that were removed in the recent past.

A geotechnical study undertaken in 1993 by the University of Cairo for the Franco-Egyptian Mission determined that there were two primary causes of damage in the tomb: mechanical stress of the rock and one or more fires that damaged the pillars, walls, and ceiling. Despite the damage, it was determined that the tomb is not at risk of collapse. More recent geological and geotechnical assessments of the tomb have attributed areas of loss of the tomb to the steeply dipping joint planes of the rock. While this is a factor in the rock loss and instability of the pillars, they have further been damaged by rock swelling and shrinking resulting from flooding. Christian Leblanc has noted that during the 1994 flood, water rushed into the tomb entrance from runoff.

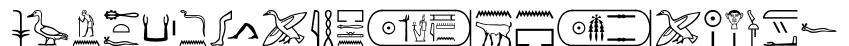

Hieroglyphs

Prince Pareherunemef

The King's eldest son of his body, Charioteer of the Great Stables of Userma'atre-Meryamen of the Residence of Ramesses III, Pareherunemef

sA-nswt-n-Xt.f-smsw kTn pA iHw aA n wsr-mAat-ra-mr-imn n-Xnw ra-msw pA-ra-Hr-wnm-f

The King's eldest son of his body, Charioteer of the Great Stables of Userma'atre-Meryamen of the Residence of Ramesses III, Pareherunemef

sA-nswt-n-Xt.f-smsw kTn pA iHw aA n wsr-mAat-ra-mr-imn n-Xnw ra-msw pA-ra-Hr-wnm-f

Queen Minefer

King's Mother, Minefer

mwt-nswt mi-nfr

King's Mother, Minefer

mwt-nswt mi-nfr

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

The Italian Mission in the Valley of the Queens (1903-1905): History of excavation, Discoveries, and the Turin Museum Collection

Bibliography

Abitz, Friedrich. Ramses III. in den Gräbern seiner Söhne (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 72). Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätverlag and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986.

Brugsch, Heinrich Karl. Recueil de monuments égyptiens dessinés sur lieux et publiés sous les auspices de Son Altesse le vice-roi d'Égypte Mohammed-Saïd-Pasha par le docteur Henri Brugsch. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, 1862-1885.

Bruyère, Bernard. Mert Seger à Deir el Médineh. (= Mémoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, 58 (1929-1930). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire.

Bruyère, Bernard. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el Medineh (1924-1925). Fouilles de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire 3, 3 (1926). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire.

Bruyère, Bernard. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el Médineh (années 1945-1946 et 1946-1947). Fouilles de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire, vol. 21. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire, 1952.

Carter, Howard. Report of work done in Upper Egypt (1902-1903). Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Egypte 4 (1903): 171-86.

Champollion, Jean-François. Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie. Vol. 1-2. Paris: Firmin-Didot Frères; Geneva: Editions de belles-lettres, 1845.

Demas, Martha and Neville Agnew (eds). Valley of the Queens. Assessment Report. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2012, 2016. Two vols.

Grandet, Pierre. Ramsès III: histoire d’un règne. Collection bibliothèque de l'Egypte ancienne. Paris: Pygmalion/G. Watelet, 1993.