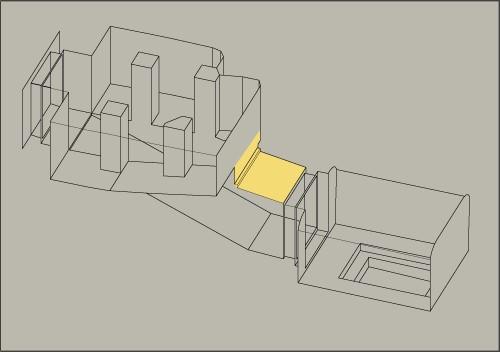

The designations used by the Theban Mapping Project for tomb components are taken primarily from the work of Thomas (1966). The letter codes are specifically related both to the position and to the function of each component in the tomb. Each tomb component can have several architectural features. Some features are unique to specific components and are described along with the component. Others are found in various parts of the tomb and will be dealt with at the end of this article.

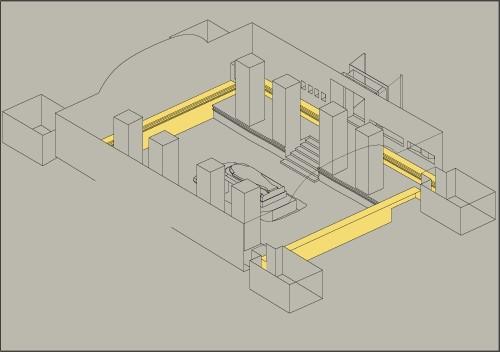

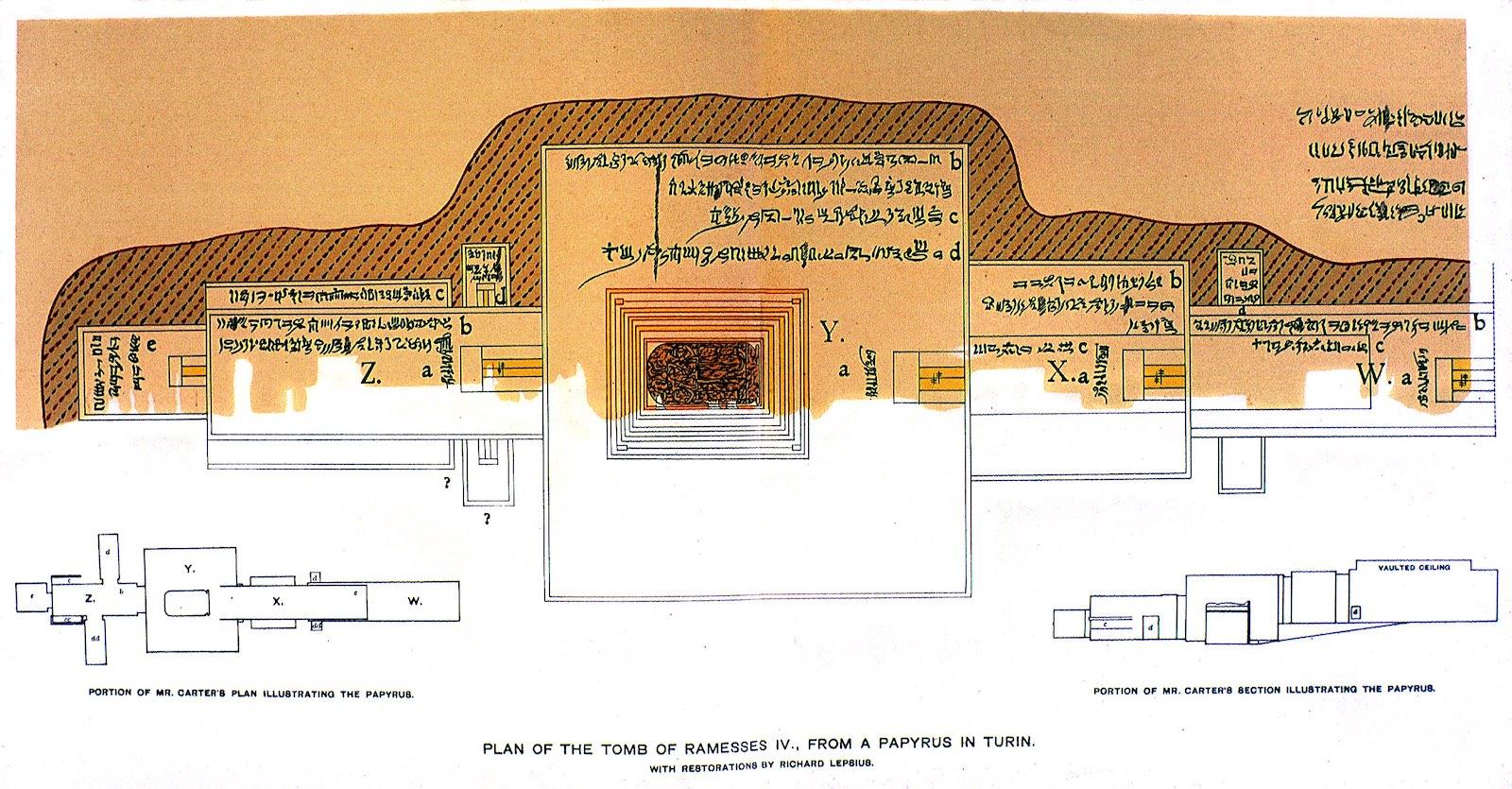

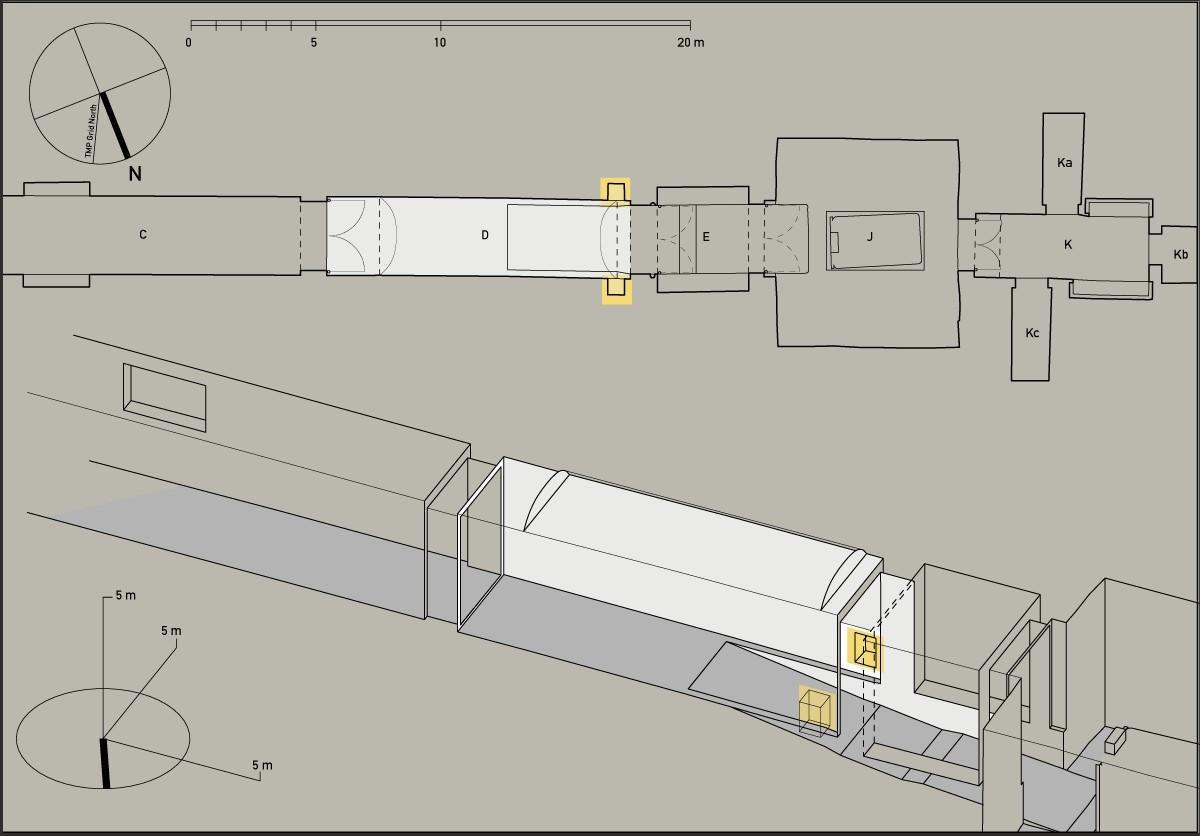

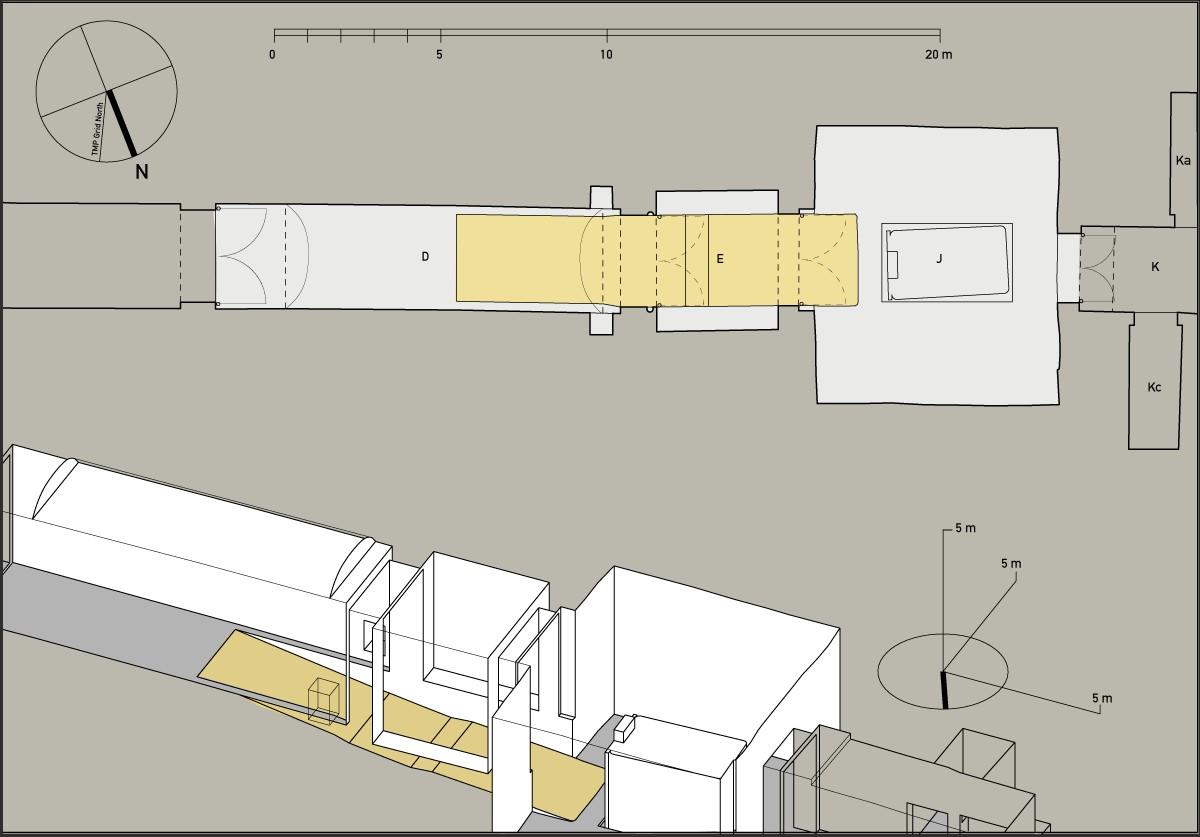

Two annotated ancient tomb plans are a principal source for knowledge of the architectural components of KV royal tombs. (For more details, see Weeks 2016.) One of these, a papyrus in the Egyptian Museum, Turin (cat. 1885), gives the plan of the tomb of Rameses IV (KV 2).

It shows a drawing of the tomb plan from corridor D to corridor K, and the side-chambers behind burial chamber J. On the other side of the papyrus, Hieratic notes give measurements of a tomb from entryway A to pillared chamber F. It is likely that this tomb is KV 9 as it was initiated under Rameses V.

A limestone ostracon, discovered either in KV 9 or KV 6 by Georges Daressy in 1888 and now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo (CG 25184), provides a complete plan of KV 6. Unfortunately, the hieratic labels on this ostracon are now difficult to read. The drawing was probably not a plan to guide the tomb builders but a record of the completed work, the equivalent of a modern engineering "as-built" drawing.

Other ancient sources that shed light on ancient terminology include papyri and Ostraca found either in the Valley of the Kings or at Dayr al Madinah, and give reports on tomb construction activities. Because the majority of these documents date to Dynasties 19 and 20, we cannot say with certainty that the same terminology was also used earlier.

A: The God's Passage of the Empty/Open Path

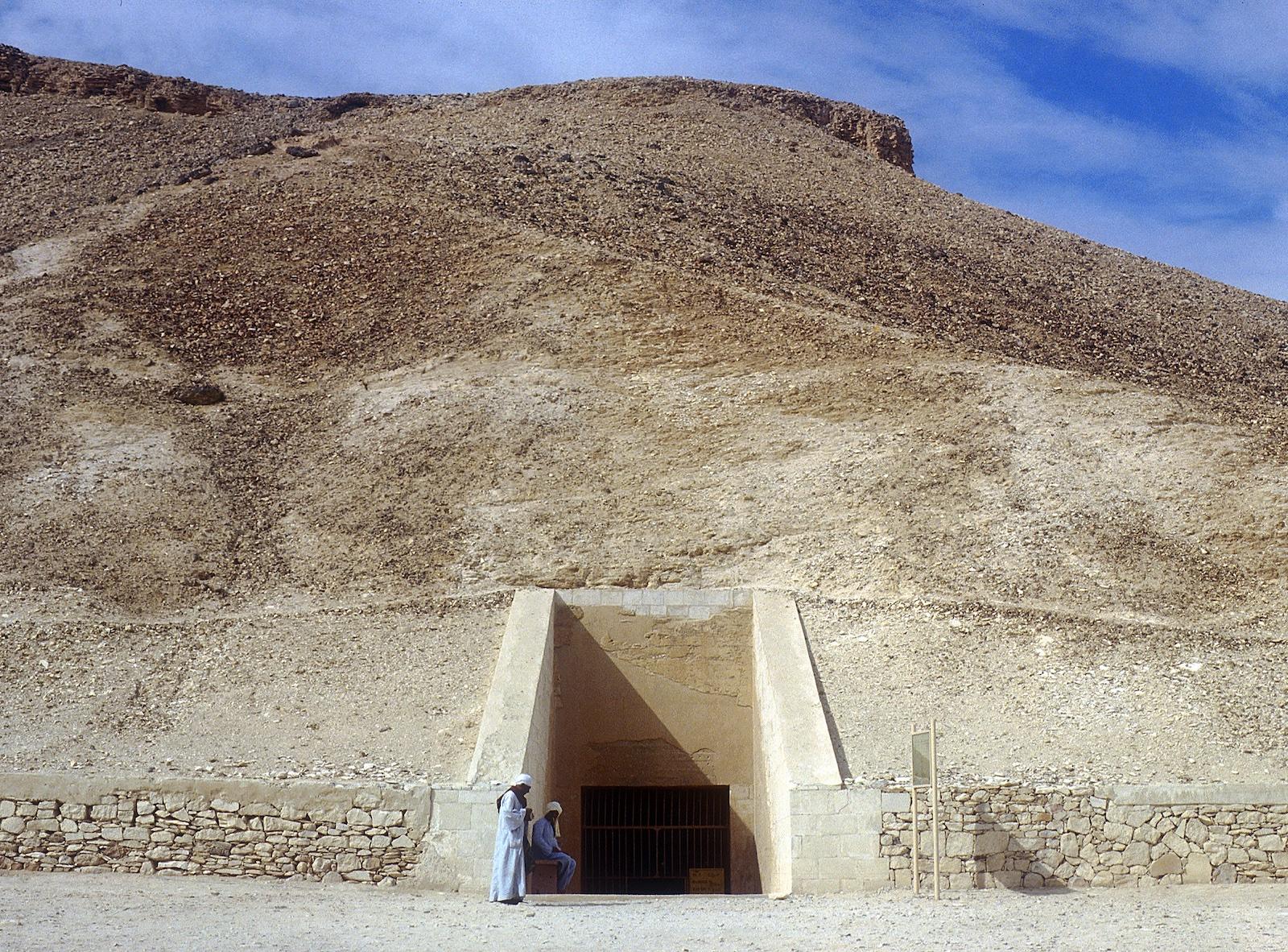

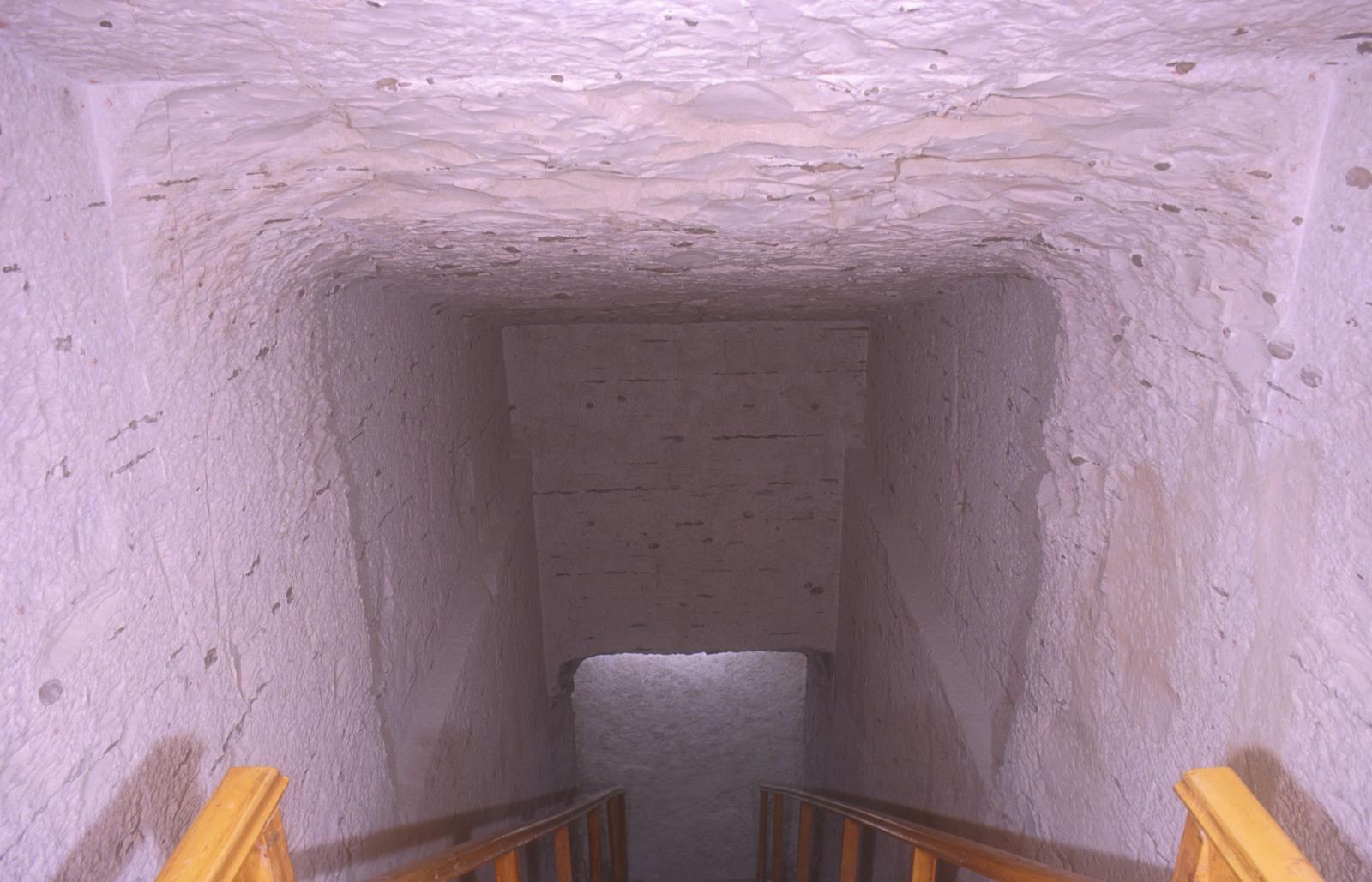

Sometimes translated as "the god's passage of the way of Shu" or "the open-air passage" (literally "the god's passage of the empty/open path"), this term on the Cairo ostracon corresponds to entryway A. When this phrase was used in the Rameside period, the entryway was a Ramp cut into the hillside, open to the sky, leading to the first gate. A is either a stairway, a ramp or a shaft cut into the rock of a hillside or cliff face. In Dynasty 18, it takes the form of a steep stairway.

In the second half of Dynasty 19 the slope of the stairway substantially decreases. In mid-Dynasty 20, the entry becomes larger than previously and the slope becomes very shallow. Rubble walls occasionally augmented the tops and front ends of the sides of Dynasty 20 entry cuttings. The sides of the entryway often were plastered, but except for two instances in Dynasty 20, were never decorated. In KV 11, two pairs of pilasters topped with the heads of horned animals were carved at the far end of the entryway sides, beneath the Overhang, just before gate B. A similar set of two pairs of pilasters was begun in a similar position at the rear of the entryway of KV 6, but the cutting was left unfinished. Some tombs simply had a vertical shaft entrance.

B: The Passage of Ra

"The passage of Ra" or "the passage of the sun" is the name given to the first corridor B on the Cairo ostracon. "The first god's passage of the sun's path" is another name given to the first corridor.

C: Second God's Passage and the Niches in Which the Gods of the East and West Rest

The components C and I sometimes are simple chambers, distinguished from corridors by the fact that their width is equal or greater than their length.

C is sometimes called the "second god's passage." The two recesses in C are called "the niches in which the gods of the east and west rest." This seems to indicate that figures of deities should be placed in them, although none have been found. However, figures of some of the seventy-four forms of the sun god in the Litany of Ra were painted in these niches, beginning with KV 17 and continuing through KV 2.

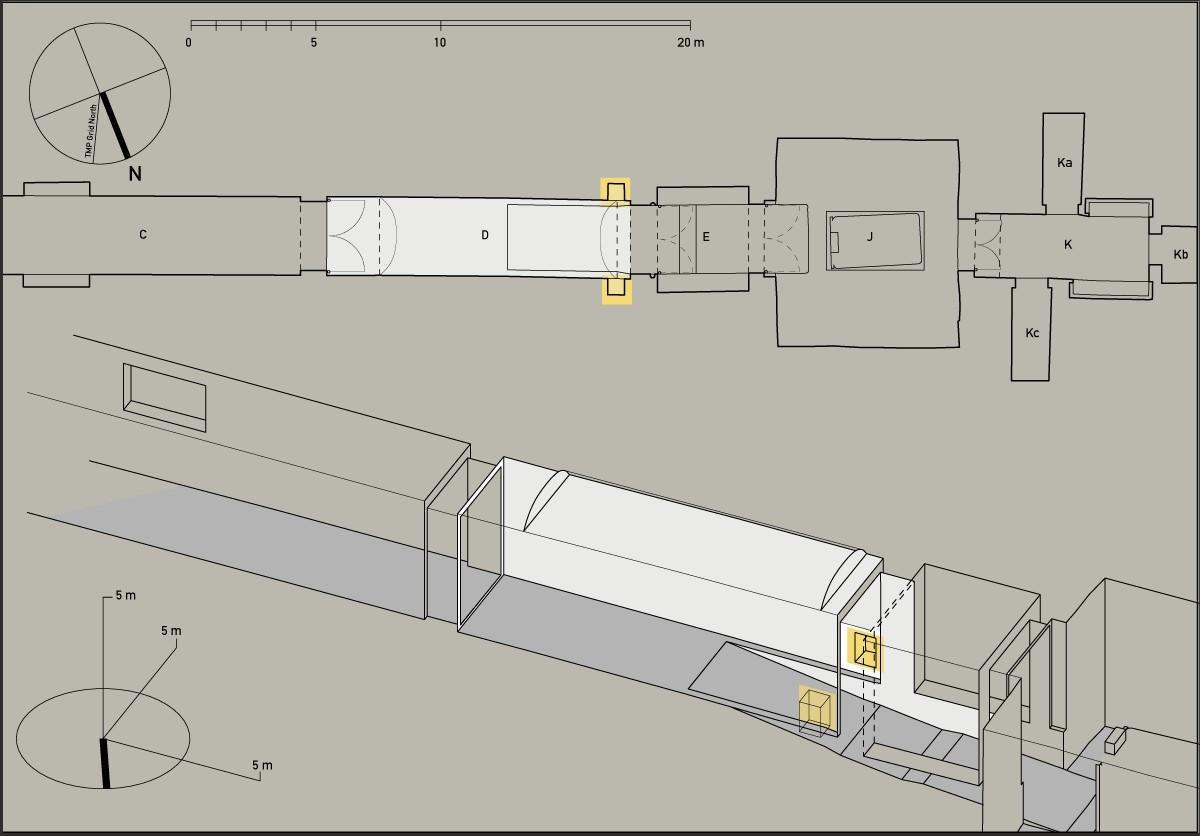

D: The Two Doorkeepers' Rooms

The two rectangular recesses at the end of the third corridor D, near the floor, are called "the two doorkeepers' rooms."

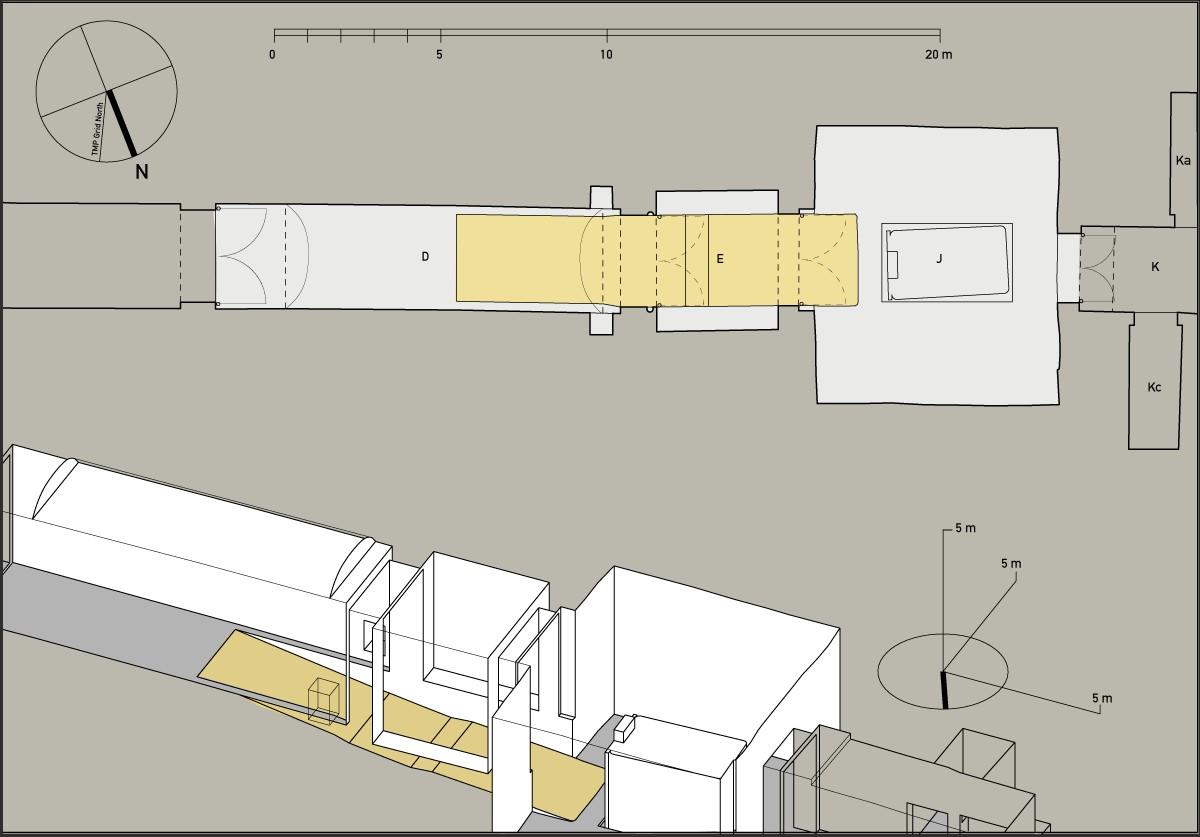

E: The Hall of Hindering/Waiting

"The Hall of Hindering/Waiting" corresponds to chamber/well chamber E, although when this term was used in the Turin plan and the Cairo ostracon, well shafts were no longer being cut into the floor of these chambers. In about half of the earlier tombs, E contained a deep well shaft.

It appears first in KV 34. In some examples, such as KV 35, KV 43, and KV 22, there is a side chamber off the bottom of the shaft.

Some Egyptologists have argued that the shaft was intended to deter tomb robbers, others that it was to collect floodwaters and keep them from entering further into the tomb. Since the integrity of the tombs depended on the remoteness and security of the Valley, thwarting tomb robbers is not a convincing argument for the shaft's purpose. The latter purpose also seems unlikely, as tomb entrances were sealed and covered. The presence of a side-chamber at the bottom of A in some tombs led to a third theory: that the shaft represents the burial place of the Memphite necropolis god Sokar, also identified with Osiris. In Rameside period royal tombs, the decoration on the walls of corridor D, preceding the Well shaft, depicts the fourth and fifth hours of the Imydwat, describing the sun god Ra's passage over the burial place of Sokar.

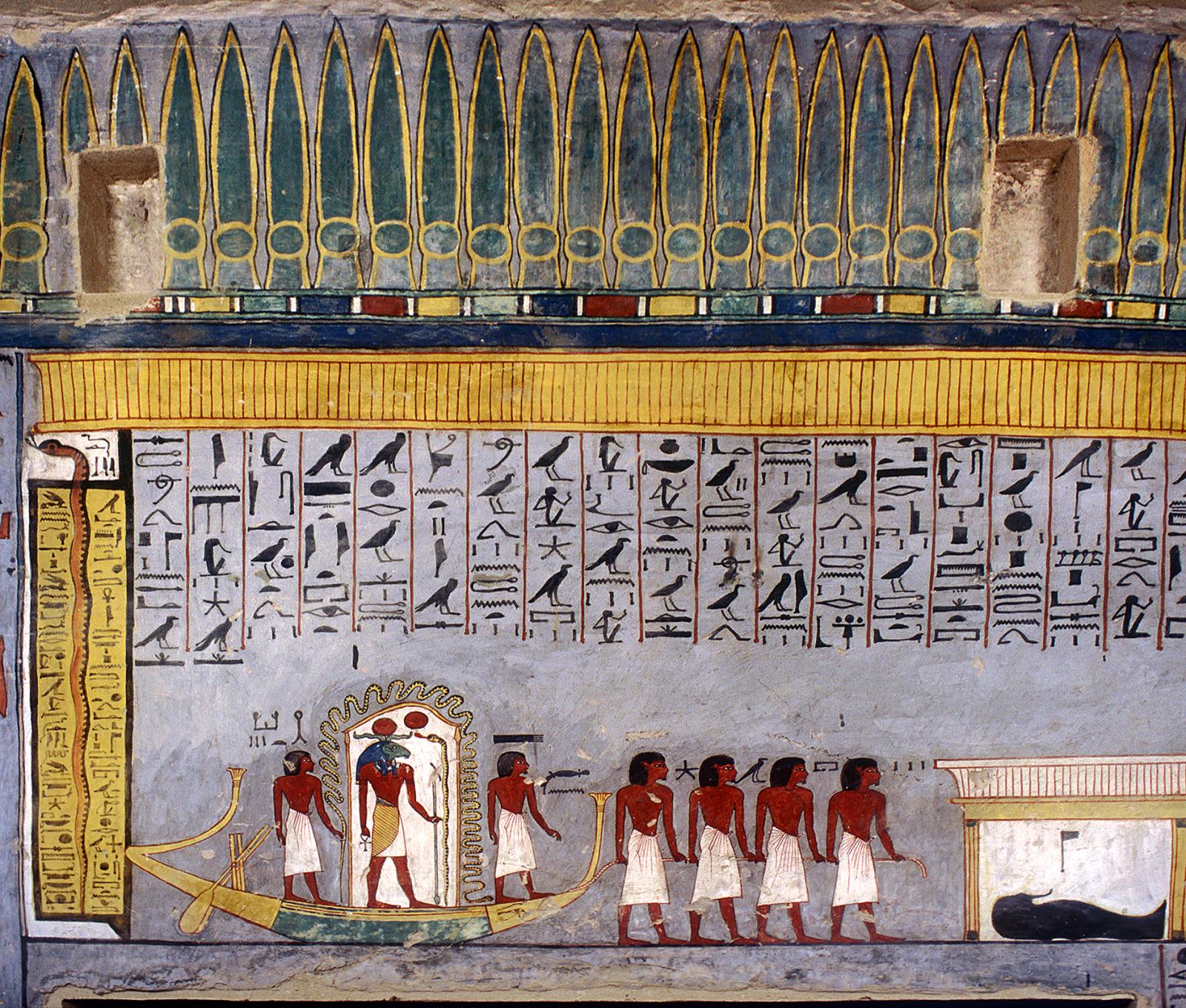

The walls of chamber E were often decorated with scenes of the king in the presences of various deities, including Hathor, Isis, Horus, Anubis, and Osiris. This decoration was usually carried over onto the blocked and plastered gateway leading to pillared chamber F, and was lost when the tombs were entered in antiquity and the wall was destroyed by thieves.

F: The Chariot Hall

"The Chariot Hall" was the name given to pillared chamber F. What particular association it had with chariots is not known, although in most royal tombs this chamber could have accommodated chariots, especially if they were partly dismantled, as was done in KV 62. Evidence of actual chariots is known from some tombs, including KV 22, KV 43, and KV 46, although none were localized in this chamber, because of the activities of tomb robbers. On the Cairo ostracon, this chamber's name is partly preserved as "the all treasury."

In tombs of Dynasty 18, this chamber served as a location for the change from one angle of axial orientation to another. During that dynasty, beginning with KV 34, the hall contained only two pillars and the stepped descent in the floor was set to the side.

It is thought that one purpose of the chamber was to provide sufficient space for maneuvering the Sarcophagus in Dynasty 18 tombs with a bent axis. Four pillars were placed in the chamber beginning with KV 17 (Sety I) and in KV 7 (Rameses II), onwards, the descent was moved to the center of the chamber and flanked by the two pairs of pillars.

Opening/Beginning (?) of Dragging

"Opening/Beginning (?) of dragging" is used on the Turin plan to designate the start of a ramp running from the end of the third corridor D of KV 2, through chamber E, to the floor of the burial chamber J, which would have served as a sarcophagus slide. On the Cairo ostracon, the descent in F is partly preserved as "the descent."

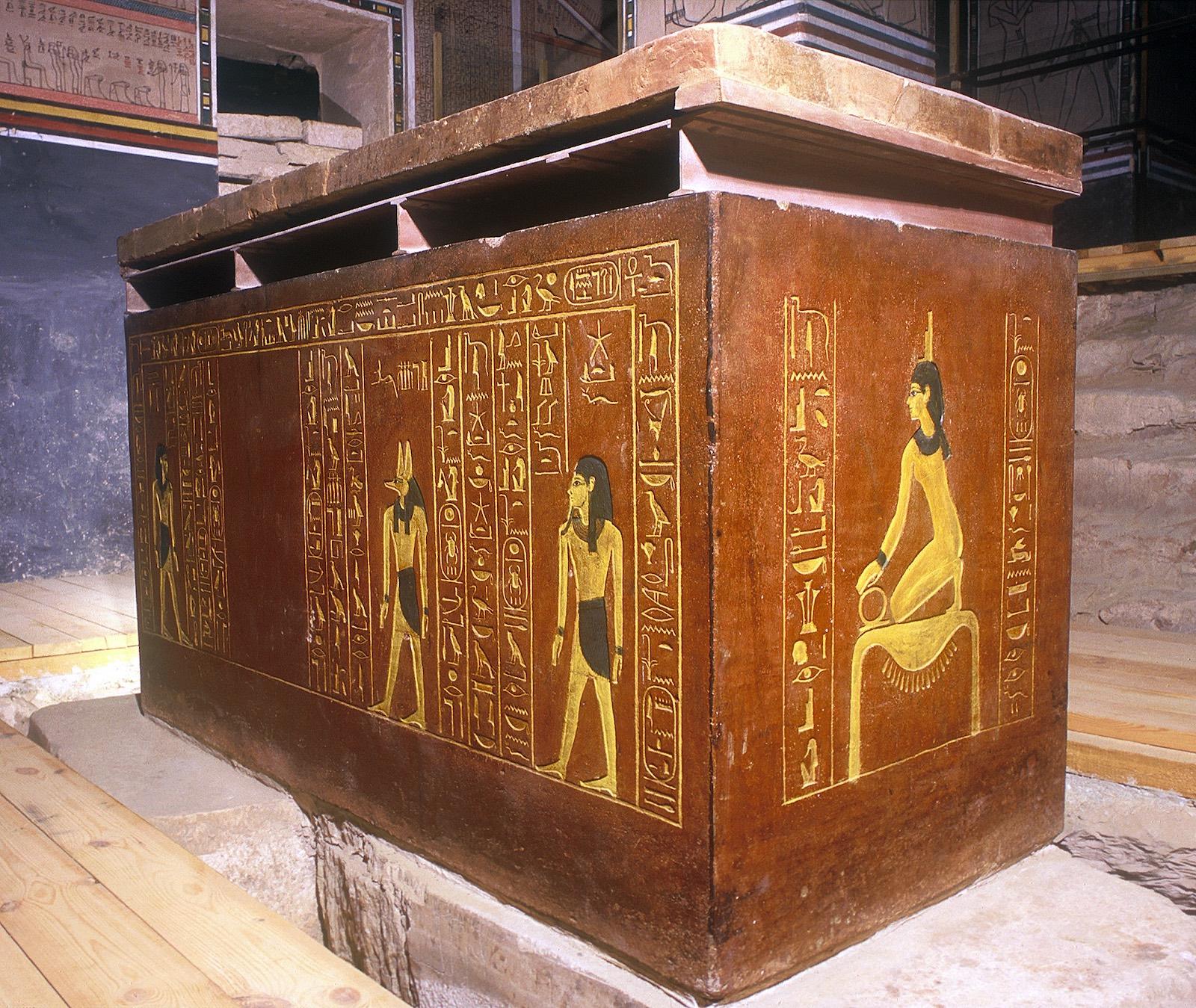

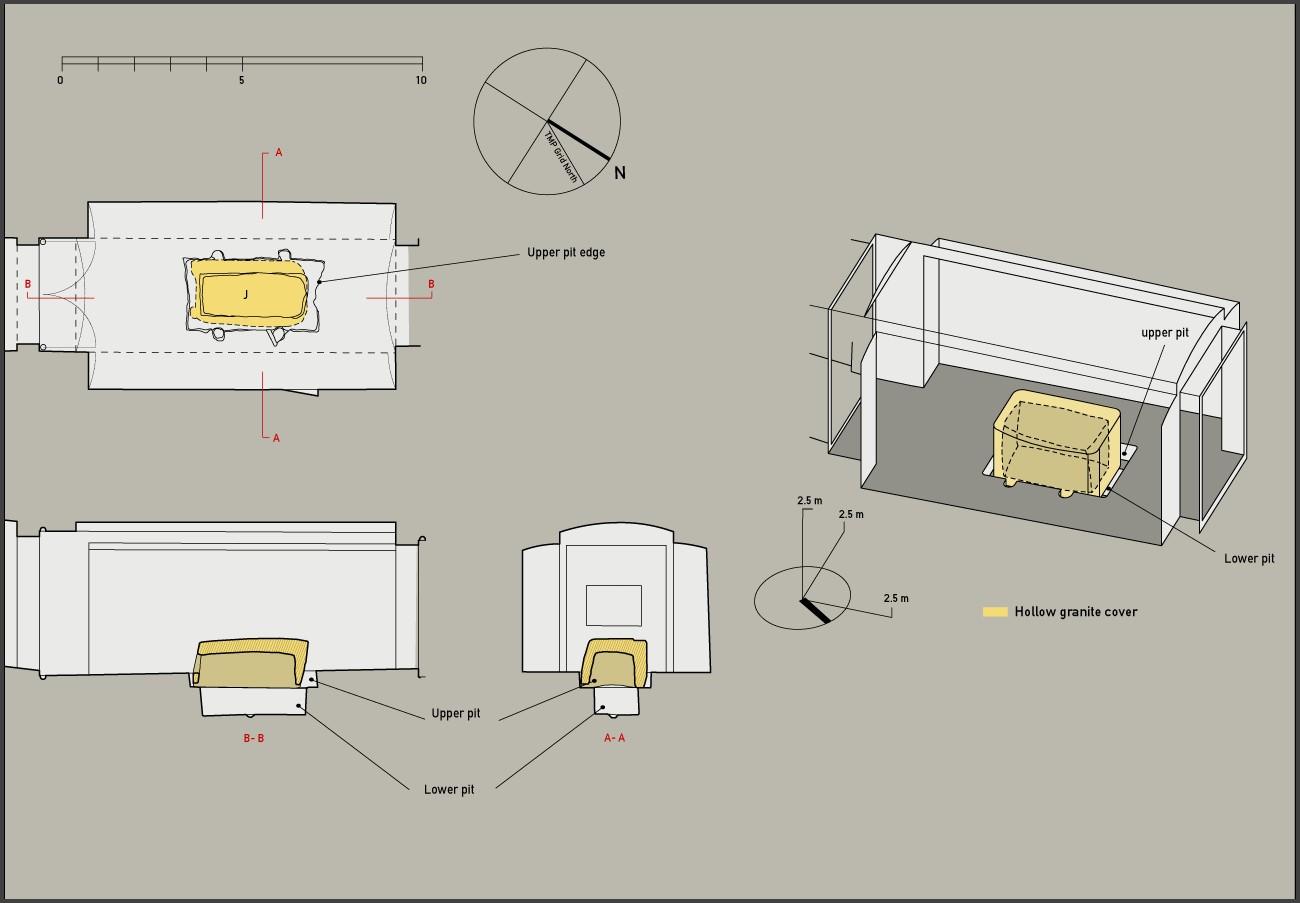

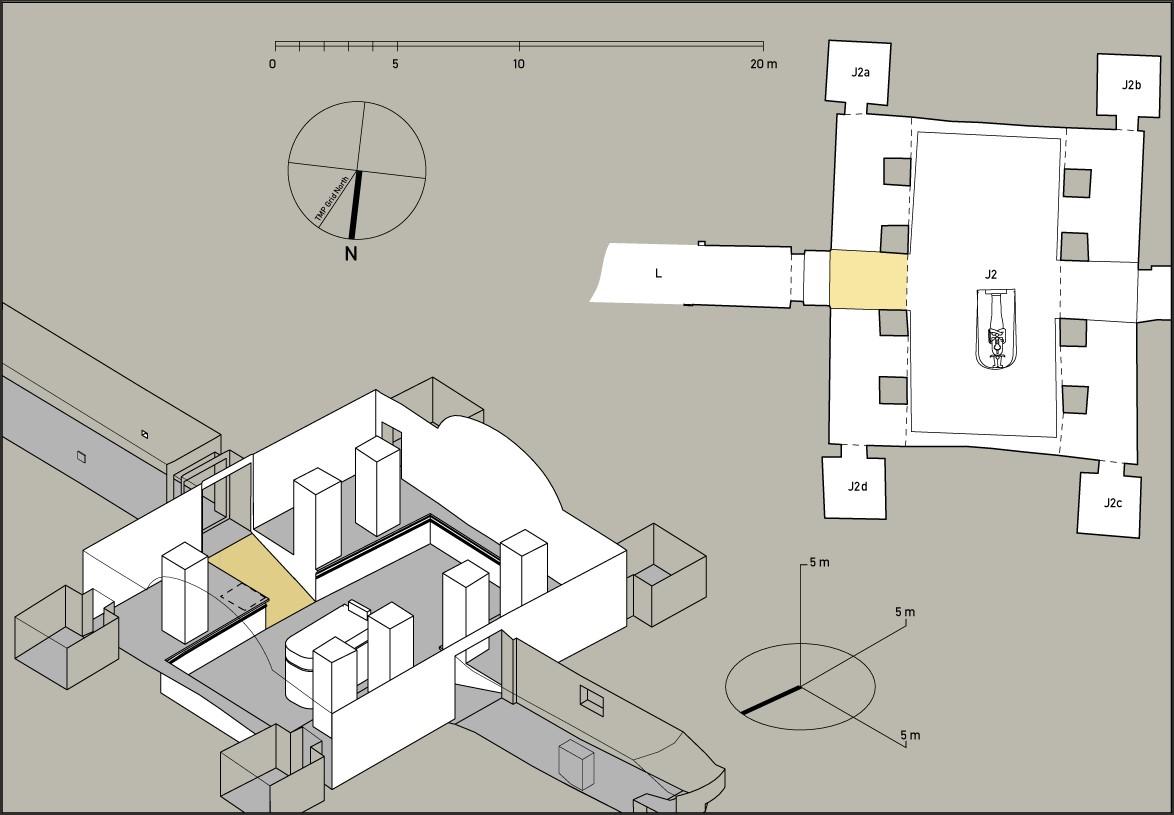

J: House of Gold Wherein One Rests

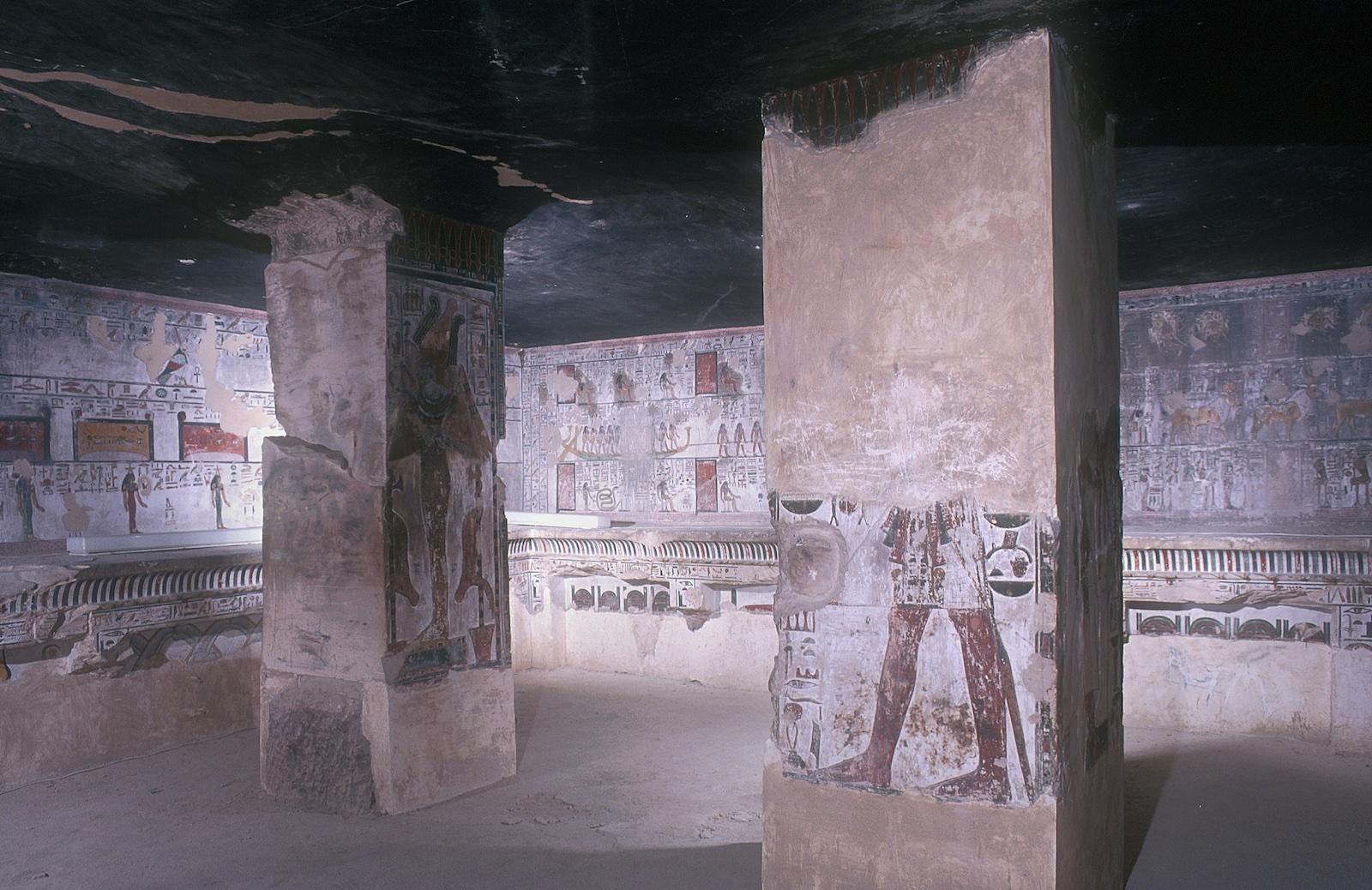

J is the most important part of the tomb, and from Thutmes III onwards, New Kingdom royal examples were always decorated. The apparent exception, KV 43, may be the result of lack of sufficient time to carry-out the decoration after the Thutmes IV's death, since the walls had only been smoothed before plastering.

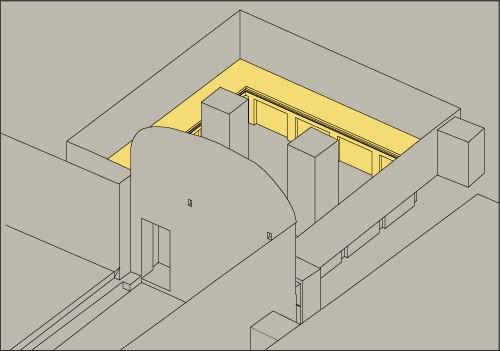

The sarcophagus was placed at the rear of the chamber, beyond a set of pillars in a lower (sunken) level, beginning with KV 35. From the reign of Rameses II through the reign of Rameses VI, the sunken area with the Vaulted ceiling above was moved to the center of the chamber. There is usually a stepped or ramped descent cut from the entrance of the tomb to the sunken area. Two sets of four columns on the upper level flanked the sunken central area to the front and rear.

In the better-preserved examples, the upper edges are carved as a cavetto cornices and the vertical faces are decorated with images of burial equipment.

In some instances, the actual burial chamber is not location after pillared chamber F. Instead, due to time constraints brought about by the unexpected death of the king, a corridor or a chamber, such as pillared chamber F, would be converted to use as the burial chamber. Such a conversion occurred in KV 2 (Rameses IV), and probably KV 23 (Ay). Examples of the conversion of a corridor into a burial chamber are found in KV 1 (Rameses VII), KV 10 (Amenmeses), KV 15, (Sety II), KV 19 (Prince Mentuherkhepeshef), and perhaps KV 16 (Rameses I).

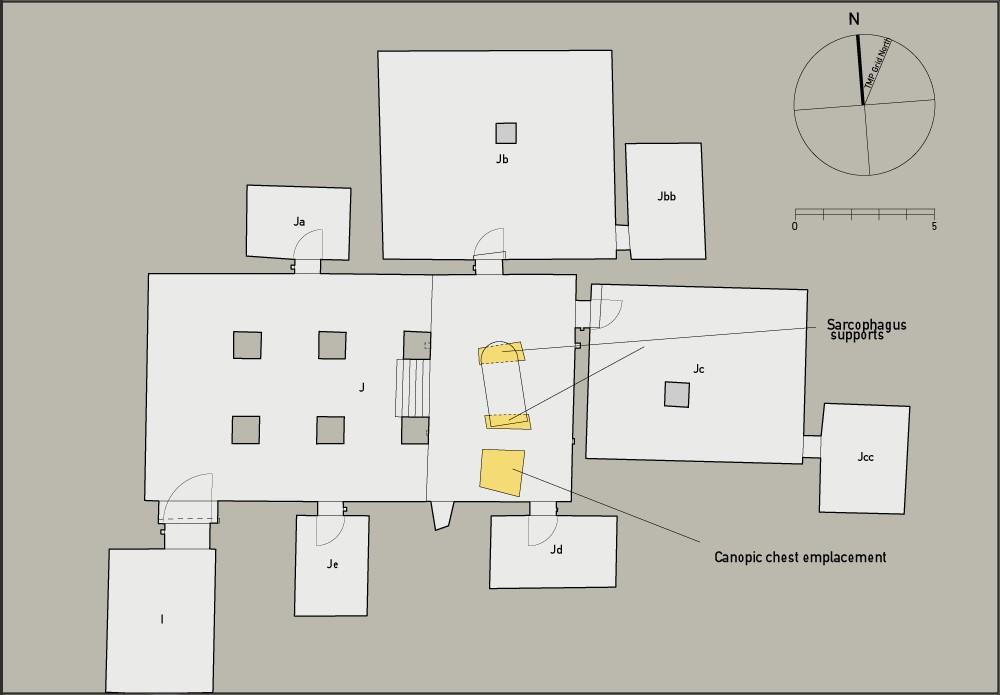

In KV 2 on the Turin plan, the name of this chamber is thought to allude either to the yellow background color of the walls or to gold coffins and gilded shrines like those found in KV 62. The sarcophagus was often placed on or in some sort of structure or excavation set into the floor of the burial chamber. In many instances, blocks of either fine quality limestone or "Egyptian alabaster" served as a base and were placed in a recess or recesses cut into the floor (KV 34. KV 35, KV 22, KV 62, KV 23, KV 8.

In other cases, the sarcophagus was placed in a depression cut into the floor (KV 47, KV 9). Many of these depressions have been recently covered by modern flooring.

Burial pit

Sometimes the body was placed in a pit cut into the floor of the burial chamber, either in a Coffin or without one. Provision was made for covering it, either with stone slabs (KV 5, KV 19) or a single stone cover (KV 1). This is actually a substitute for the freestanding box and lid that comprise a sarcophagus.

Canopic chest Emplacement

Although few of these chests have been found in their original setting, the canopic chest was probably placed either at the foot of the sarcophagus or in a separate side chamber off the burial chamber (KV 62). The only certain emplacement for a canopic chest is the square pit at the foot of the sarcophagus in the burial chamber of Amenhetep III (KV 22). There is also one emplacement for a canopic jar, in KV 1.

Magical brick niches

Four rectangular holes to hold magical bricks were cut into the walls of the burial chamber surrounding the sarcophagus from the reign of Amenhetep II through at least that of Rameses II. Since the wall surfaces are still plastered in the expected positions for brick niches in KV 8 and KV 14, and the burial chambers were never completed in other Dynasty 19 royal tombs, we cannot say if the practice continued beyond the reign of Rameses II. In tombs of Dynasty 18, one niche is cut into each wall of the part of the burial chamber containing the sarcophagus.

From the reign of Horemheb through that of Rameses II, the niches are placed as pairs high in the walls opposite the head and foot ends of the sarcophagi. They were made to hold mud bricks incised with protective texts from spell 151 of the Book of the Dead and with figures attached (a mummy, a jackal on a shrine, a Djed-pillar, and a torch).

Vaulted Ceiling

Through the reign of Horemheb, the ceiling above the sunken portion of the burial chamber was flat, but beginning with Sety I it was carved as a vault. The vaulting, sometimes called barrel vaulting, has a semicircular profile, usually with an axis parallel to the long axis of the burial chamber.

Side Chambers (Fa, Ja-Jd, etc.)

Side chambers are most often located off pillared chamber F (usually one side chamber with a pair of pillars) or burial chamber J (usually four).

In a few cases they open off corridors (as in KV 6 and KV 11). Some were intended to hold food offerings and other funerary equipment. These are labeled according to the architectural component from which they are accessible, from front to back and left to right. We also apply the term to some items that might be called large recesses, as they lack formal gates.

K, L: Treasury

These chambers, or corridors, are located on the main tomb axis beyond the burial chamber. Some examples take the form of chambers (KV 1, KV 9). In some instances (KV 2, KV 8, KV 14) they have side chambers opening off of them. On one occasion, two chambers and a corridor follow each other (KV 11). "Treasury" is one of the terms used in the Turin papyrus to refer to K and L, chambers that lie beyond the burial chamber. It might also be translated as "storeroom."

Ceiling Recesses

These shallow recesses occur directly after gates in sloping corridor ceilings. They were intended to accommodate the horizontal tops of door leaves serving to close the gates, when they were opened. Even when corridors later became more level these ceiling recesses are retained.

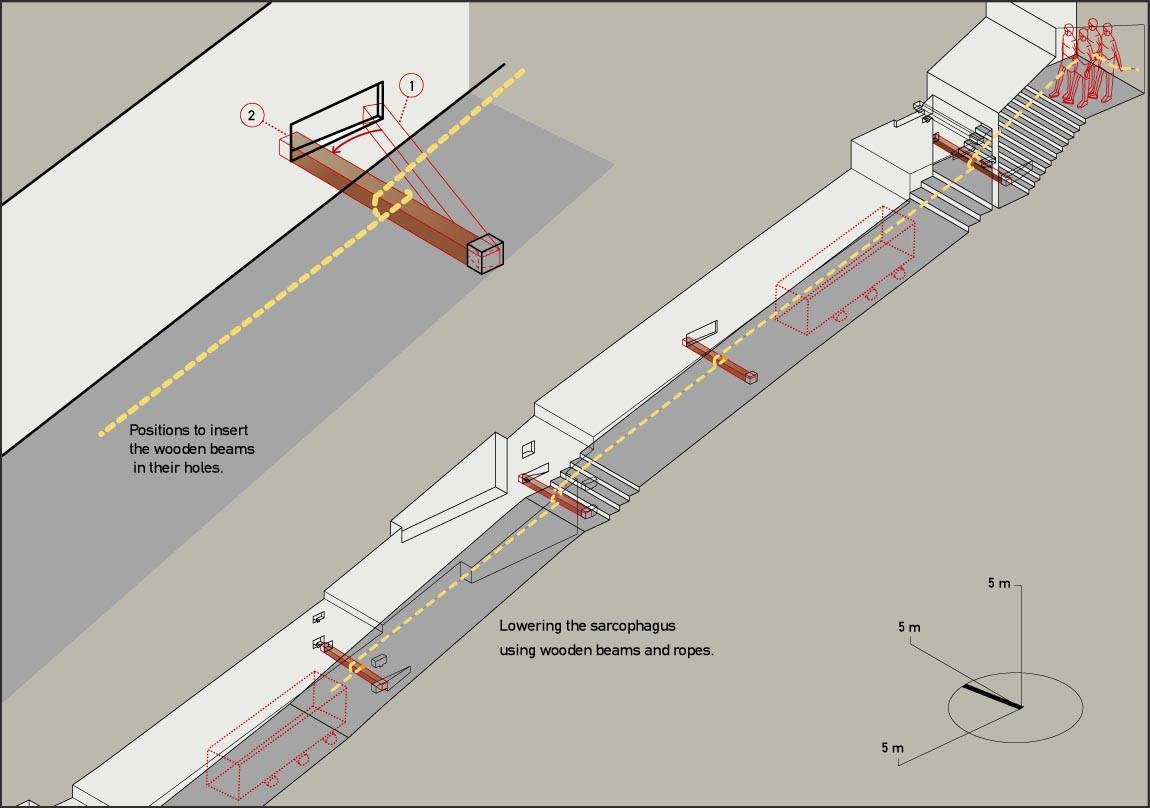

Beam holes

These specialized recesses were cut in pairs in corridor walls opposite each other, one square and the other rectangular, increasing in depth from the front to the back of the tomb. One end of a wooden beam was inserted into the square hole and the other swung in an arc into the rectangular hole. Ropes were passed around the beam and attached to a sarcophagus down-slope, and then would be carefully released to control the descent of the sarcophagus to the horizontal surface between the bottoms of the jambs.

Stairwells (C, H)

In Dynasty 18 the entryway often had stairs. Two other components (C and H) also served strictly as stairwells. There is a clear historical sequence of development for C, the third main component in the royal tomb architecture. In early Dynasty 18, it appears as a descent in the floor of chamber C. Eventually, chamber C decreased in lateral dimensions until it became simply a pair of large trapezoidal recesses at the top of the stairwell. By Dynasty 20, the stairwell was replaced by a corridor of shallow slope, with the recesses in the form of horizontal rectangles set high in the walls at its beginning. In three examples from Dynasty 18 (KV 43, KV 22, KV 57) and the tomb of Sety I (KV 17), H takes the form of a stairwell with recesses at the top.

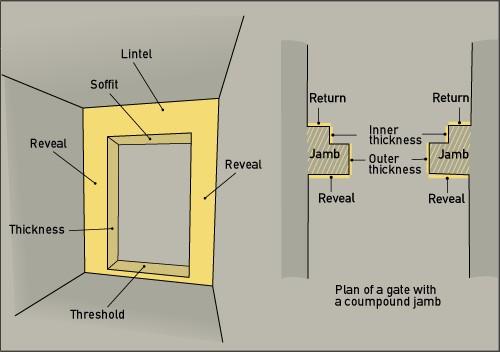

Gates (B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, side chambers)

Movement from one corridor or chamber to the next was restricted by a gate that could be closed off, either with wooden door leaves, or blocked by stones or bricks. The gates are composed of several elements. These include the lintel and soffit which are the vertical and horizontal surfaces above the opening respectively, as well as the threshold. The jambs are the sides of gates. Each jamb had three parts, from front to back, the reveals, the thicknesses, and the returns. Some gates have jambs that project farther out from the corridor walls on the reveals than on the returns, so that the thickness has two planes one deeper than the other, called outer and inner thicknesses.

This arrangement allowed the pivoting of the door leaves to be set out from the wall. In some examples, the jamb, or in compound jambs-the thicker outer thicknesses, were cut back to make room for the passage of large pieces of burial equipment such as sarcophagi (KV 8, KV 14, KV 43, KV 62). The narrowness of corridors means that the gates take the place of end walls in these components.

Corridors (B, C, D, G, H, I, K, L)

The number of corridors varies depending on the date of cutting and the amount of time available to complete the tomb. In general, there are three corridors between the entryway and well chamber E and one or two between pillared chamber F and the chamber that precedes the burial chamber. For the most part, ceiling and floor are parallel and flat and the side walls were straight. As with entryways, corridors tended to increase in width and height over time. There was also a tendency for the slope of the floor and ceiling of the corridors to decrease, until, by the second half of Dynasty 20, there was little slope at all.

Door Bolt Hole

Evidence for locking doors with horizontal sliding bolts can be seen in the gate thicknesses of some tombs. In a few instances, these occur in one of the thicknesses of a corridor gate, such as gate I of KV 57 but more often in the gates leading into side chambers, particularly those opening off the burial chamber. The hole served to receive the end of a horizontal sliding wooden bolt attached to the door leaf.

Descents (B, C, F)

Movement from one chamber to a lower part of the tomb was sometimes by means of a descent cut in the floor of a chamber. This descent shares the same letter designation with the chamber. It could be stepped, or have a smooth sloping floor surface.

Center Descent

A center descent is primarily found in pillared chamber F of Dynasties 19 and 20 royal tombs; the descent is cut into the floor in the center of the chamber, and was usually flanked by two pairs of pillars, as in KV 15.

Side Descent

In Dynasty 18 royal tombs, the descent was cut in to the floor of a chamber near one of the side walls, usually the left.

Recesses

This feature occurs in several different components. One type we met with in the discussion of stairwells. Another form of recess found at the end of corridor D in Rameside royal tombs from the reign of Merenptah onwards is rectangular with a vertical axis and set near the floor. Recesses sometimes also occur in burial chambers or in side chambers, and are sometimes decorated.

Ramps

Sometimes a short ramp occurs at the end of a corridor, and even in some cases, continues through the subsequent chamber. In burial chambers with sunken central parts, access is often via ramps.

Steps

Steps can occur in the entryway, in descents, in burial chambers, and in gates.

Divided Stairway

This stairway has a central ramp flanked by steps. It can occur in the entryway, in corridors and descents. The ramp is often called a "sarcophagus slide" from the mistaken idea that it was used when the sarcophagus was lowered into the burial chamber. It is more likely that the sarcophagus was installed before the fragile steps were cut. Similar forms of stairways are known from New Kingdom temples and may have served as ascending approach ramps to aid the two rows of priests carrying processional statues and boats. The similar arrangement in royal tomb descents may have aided the burial party carrying the mummy in its coffin. It could also have had some symbolic association with temple architecture.

Pillars

In New Kingdom royal tombs, pillars are straight-sided and usually square in section, approximately two cubits to a side, although examples of rectangular ones are also known. Pillars occur most often in chamber F and burial chamber J, although some occurrences in side chambers off these two chambers are known when the dimensions are sufficiently large.

Pilasters

Aside from the intentionally carved pilasters found at the entryways of KV 6 and KV 11, pilasters found in other parts of tombs such as KV 9 and KV 14 are actually the result of the unfinished cutting of pillars that had not been completely freed from the surrounding bed rock.

Overhang

The rock above and before the lintel of the first gate was often not cut away and covered the inner end of the entryway A. Overhangs are also found inside tombs above the ends of descents such as descent F, or at the rear of stairwells.

Benches

Beginning with KV 17, low narrow projections line the walls of one or more side chambers off the burial chamber. From the reign of Rameses II to the end of Dynasty 19, benches are also found in the burial chamber, along the front and rear walls on the upper level. Cavetto cornices were sometimes carved into the upper edges of the benches as well.