Wadi D-1

Menhet, Menwi & Merti

Entryway A

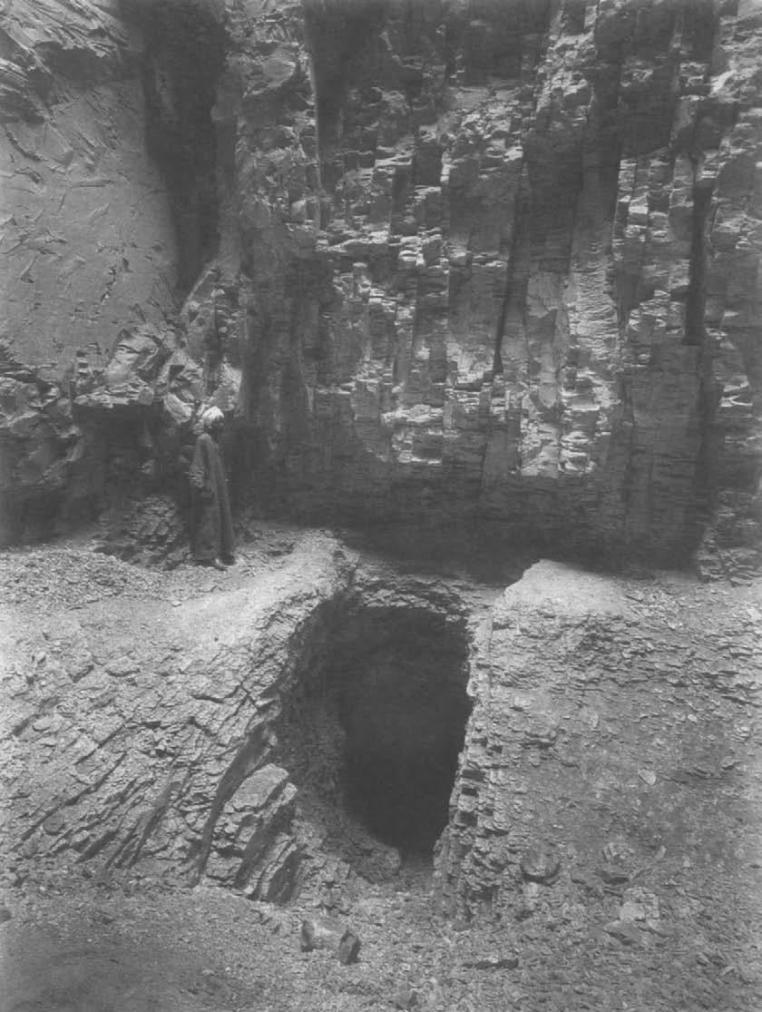

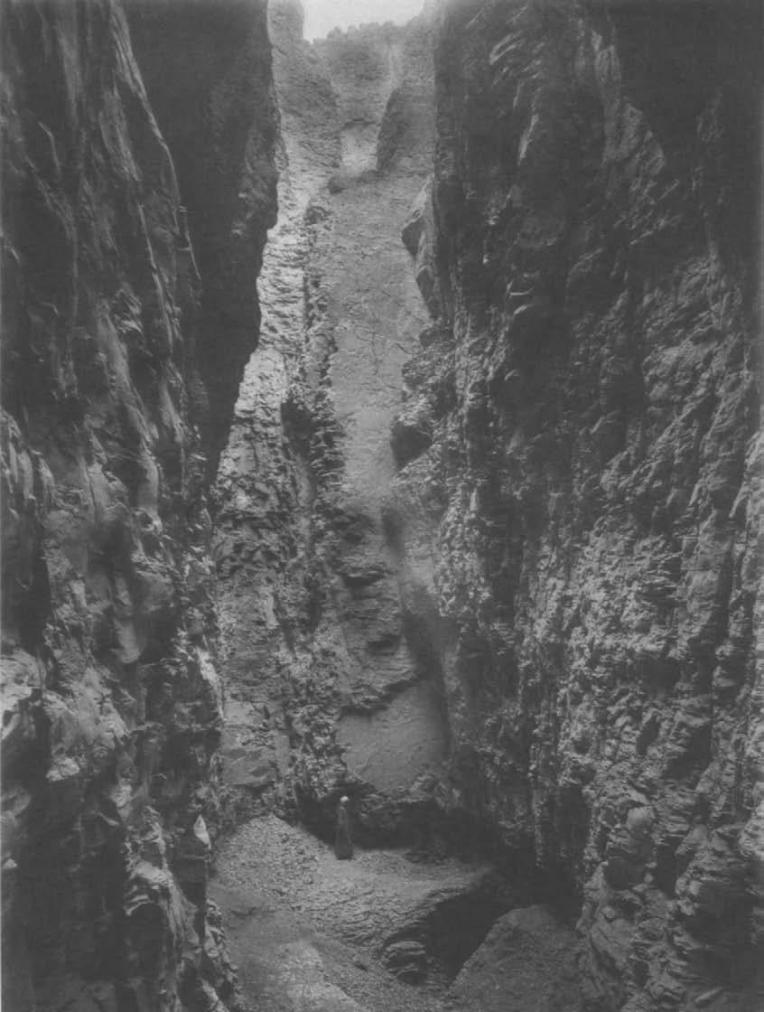

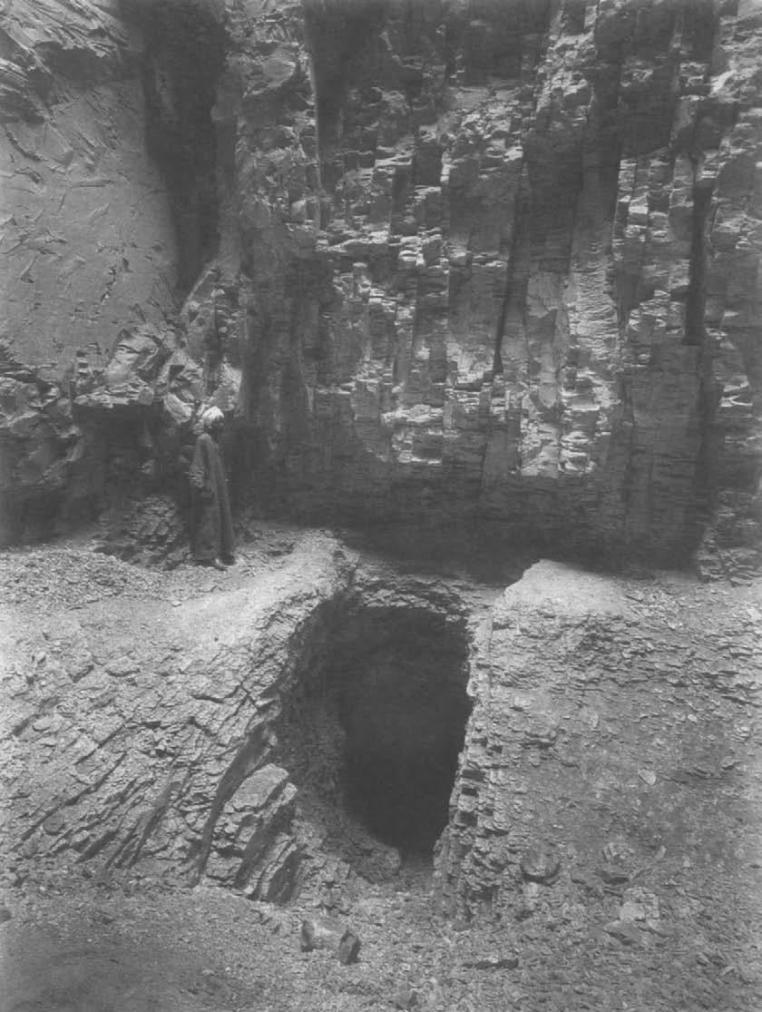

See entire tombThe entryway was excavated down into the platform that forms the cleft floor (some 10 m above the valley floor). It is well hidden and not visible from the valley. The entryway has poorly cut Steps and the walls are highly fractured and undecorated.

Corridor B

See entire tombThis long, unevenly cut corridor lies on axis with the tomb's entrance and is orientated southeast-northwest. There are remains of a doorway on the northwestern side, and a sill on the southeastern side that may have formed part of the gate separating the corridor from the burial chamber. The walls in this corridor are highly fractured, unplastered, and undecorated.

Burial chamber C

See entire tombThis vaulted burial chamber lies perpendicular to the tomb’s original axis and is orientated northeast-southwest. Large pieces of limestone have fallen from the ceiling, and the walls and ceiling are highly fractured and have been blackened by smoke from robbers’ fires and bats.

Chamber plan:

RectangularRelationship to main tomb axis:

PerpendicularChamber layout:

Flat floor, no pillarsFloor:

One levelCeiling:

Vaulted

About

About

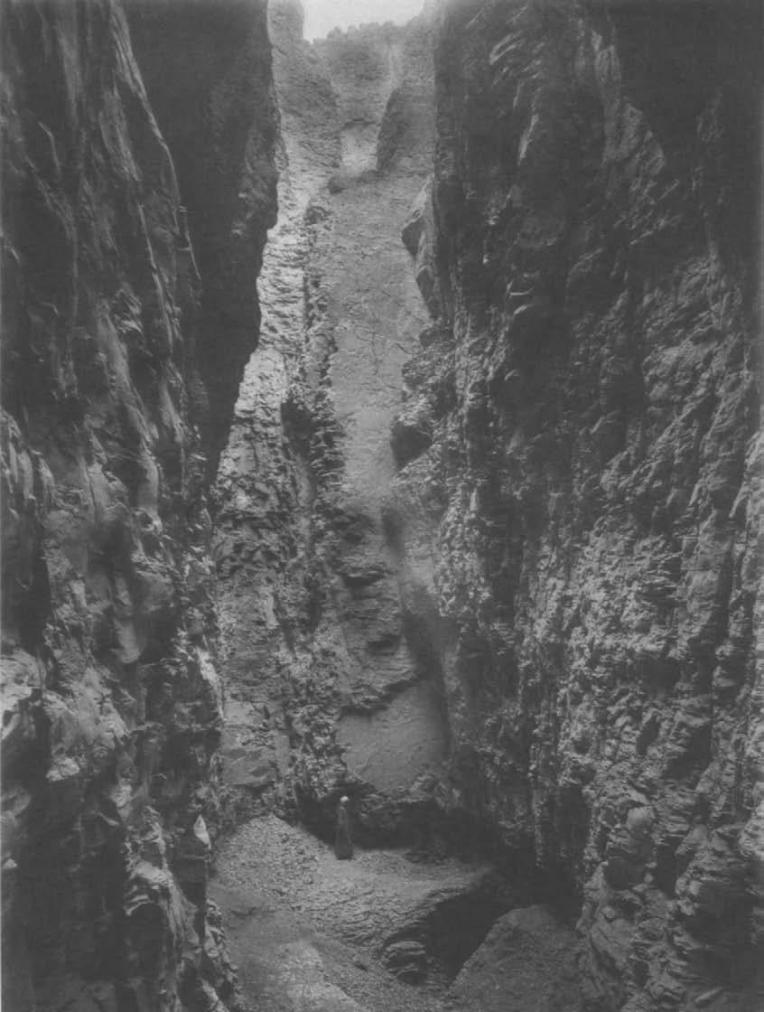

Wadi D-1 is located in a water-worn cleft of a cliff at the head of Carter’s Wadi D. The tomb is situated deep at the back of the cleft and was excavated down into the platform that forms the cleft floor (some 10 m above the valley floor). It is therefore well hidden and not visible from the valley. The entryway (A) consists of poorly cut Steps leading down into a long, unevenly cut descending corridor (B). This corridor opens into the northern corner of a vaulted burial chamber (C) that lies perpendicular to the tomb’s original axis. According to Christine Lilyquist, the tomb’s plan is consistent with the chronologically close tombs of Wadi C-1, believed to belong to Neferure, and Wadi A-1, belonging to Hatshepsut as Great Royal Wife. All three tombs turn to the right from the descending corridor. Elizabeth Thomas also noted that the lack of decoration is a typical feature for tombs assigned to queens of the 18th Dynasty.

Wadi D-1 was discovered by locals from the West Bank in 1916. Word quickly spread through Luxor that the tomb was filled with gold objects and jewelry that were indicative of royalty. Approximately 1 month later, the Antiquities service excavated the tomb. While they did uncover further objects (now in Cairo Museum), a large portion of the tomb’s contents had already been removed by tomb robbers in the month prior and sold to antiquities dealers. Howard Carter, who excavated and studied the tomb shortly after the antiquities service’s excavation had concluded, spent several years thereafter attempting to locate the stolen objects on the antiquities market. A large portion thereof is now part of the Egyptian collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

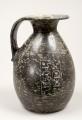

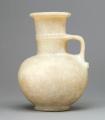

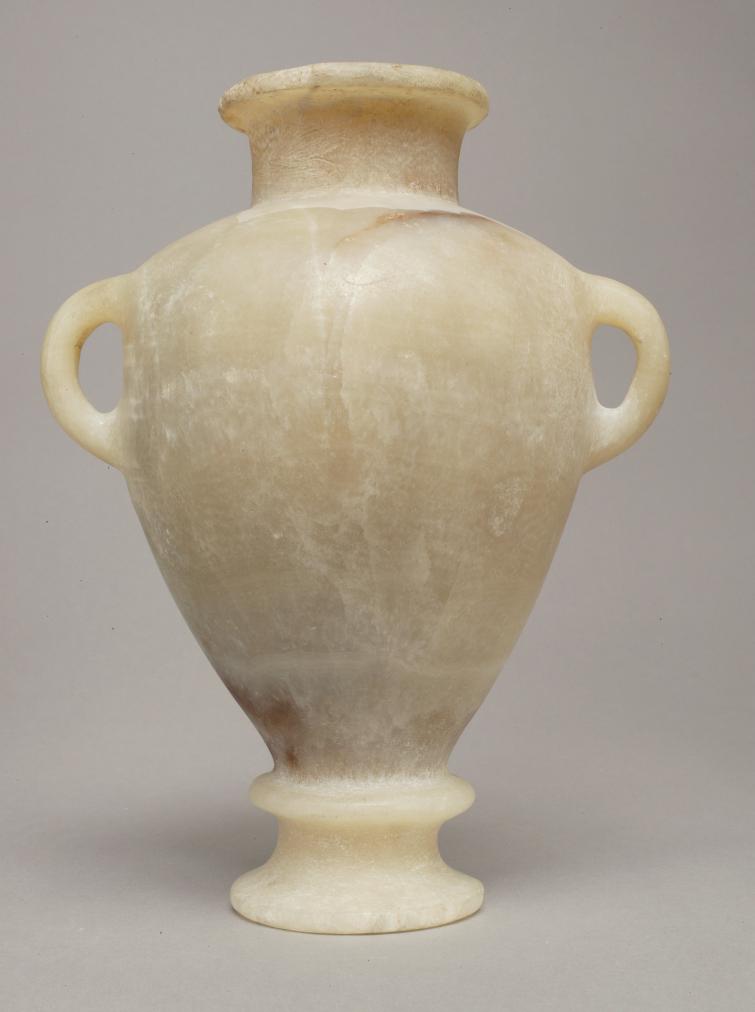

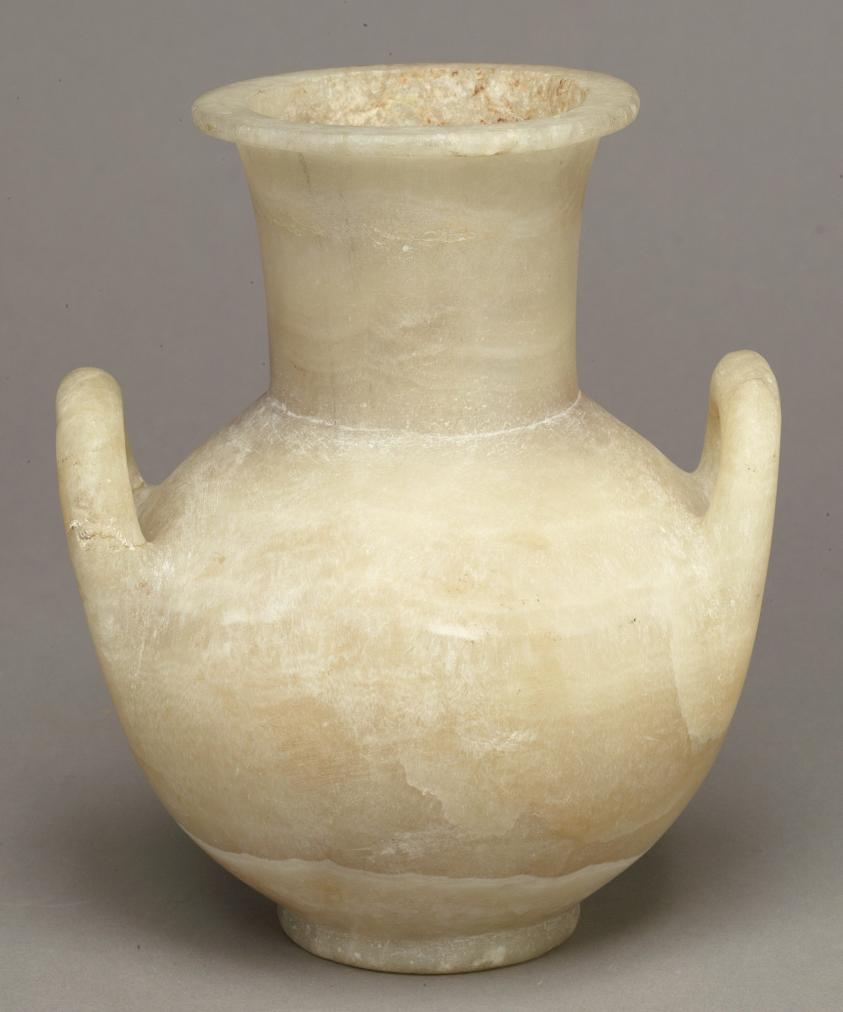

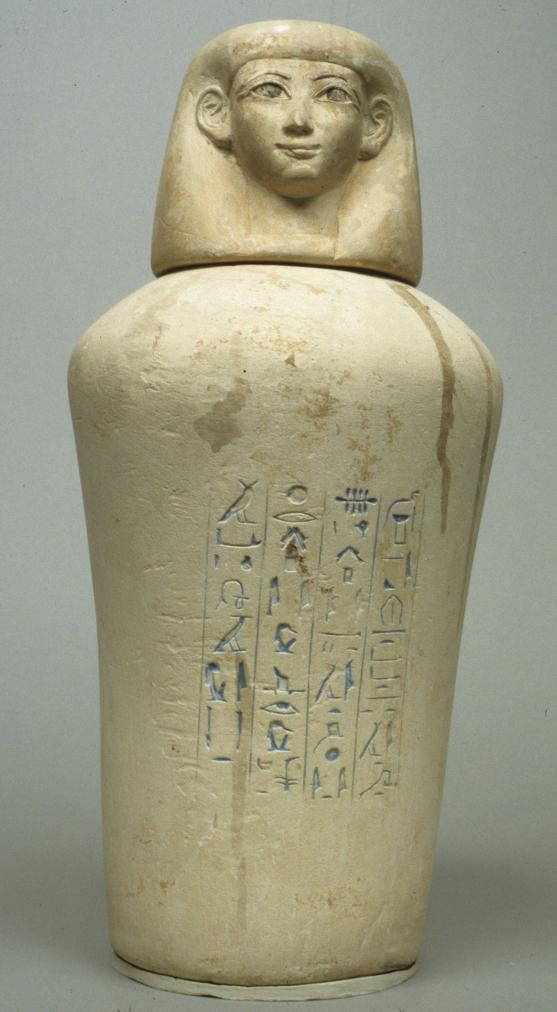

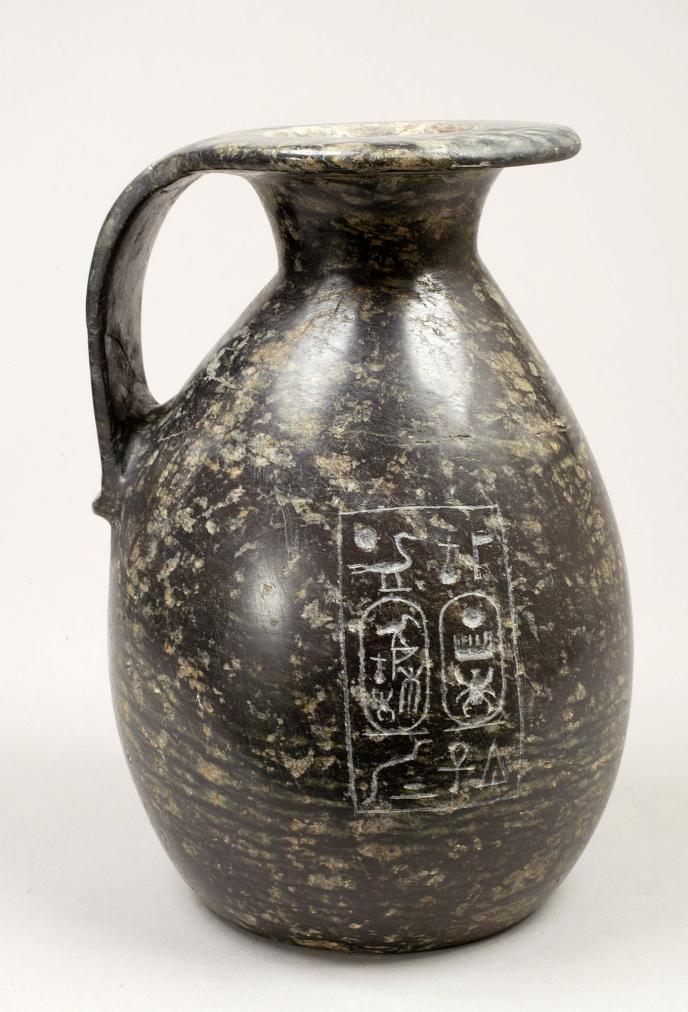

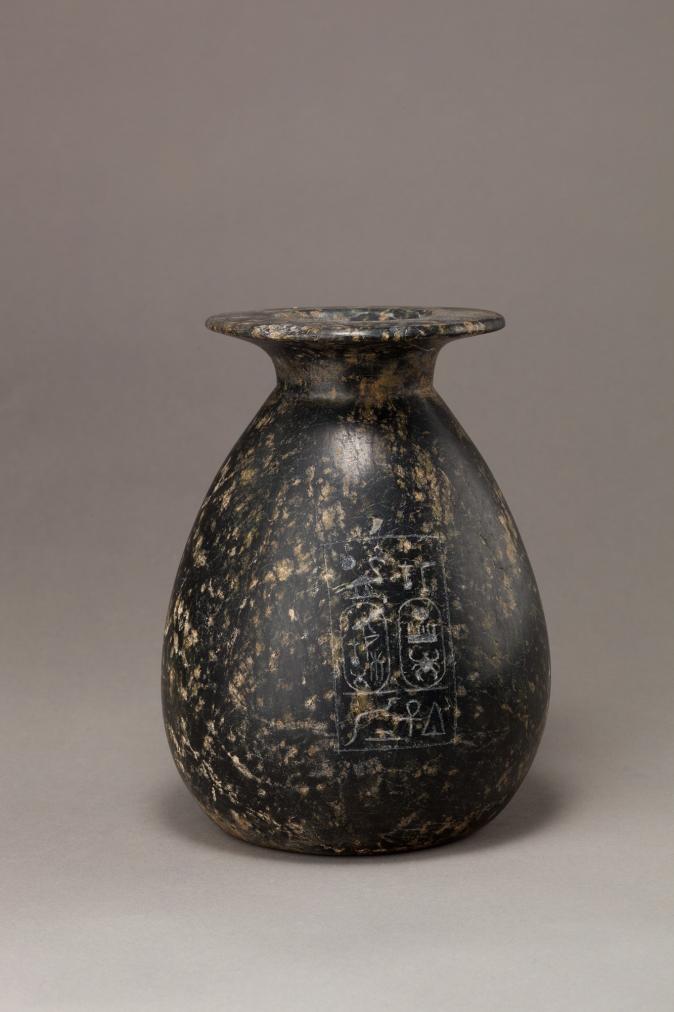

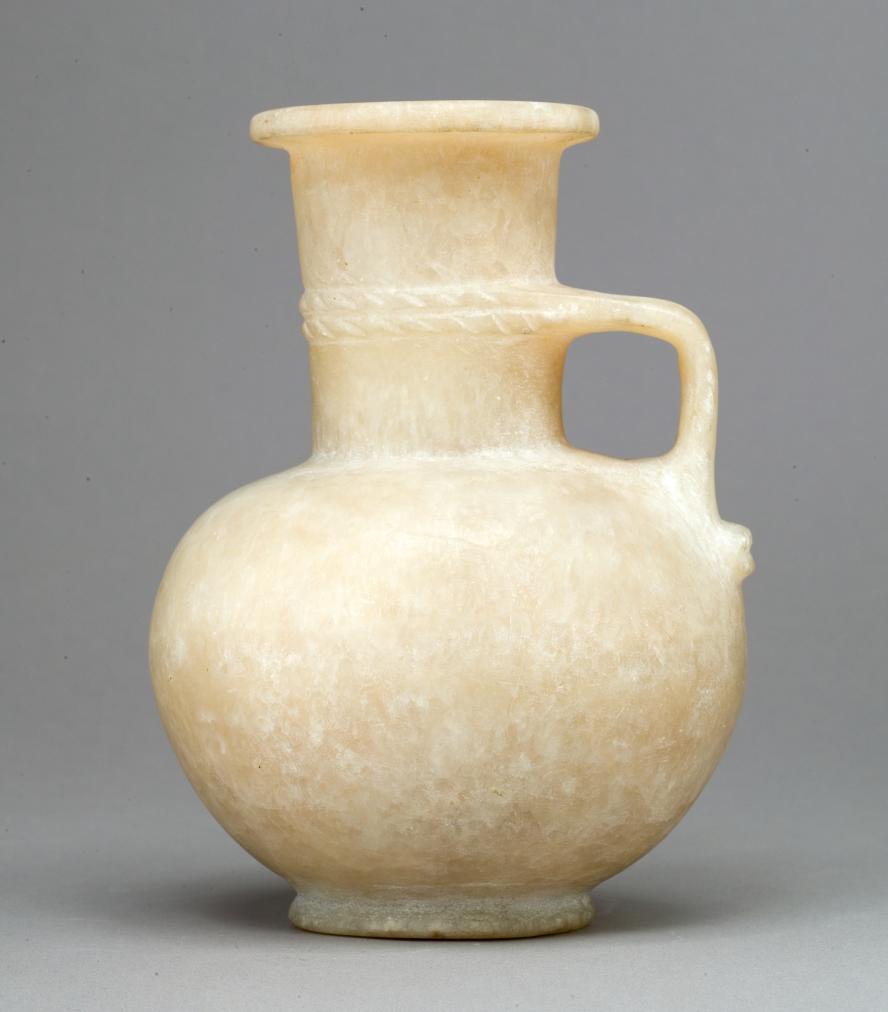

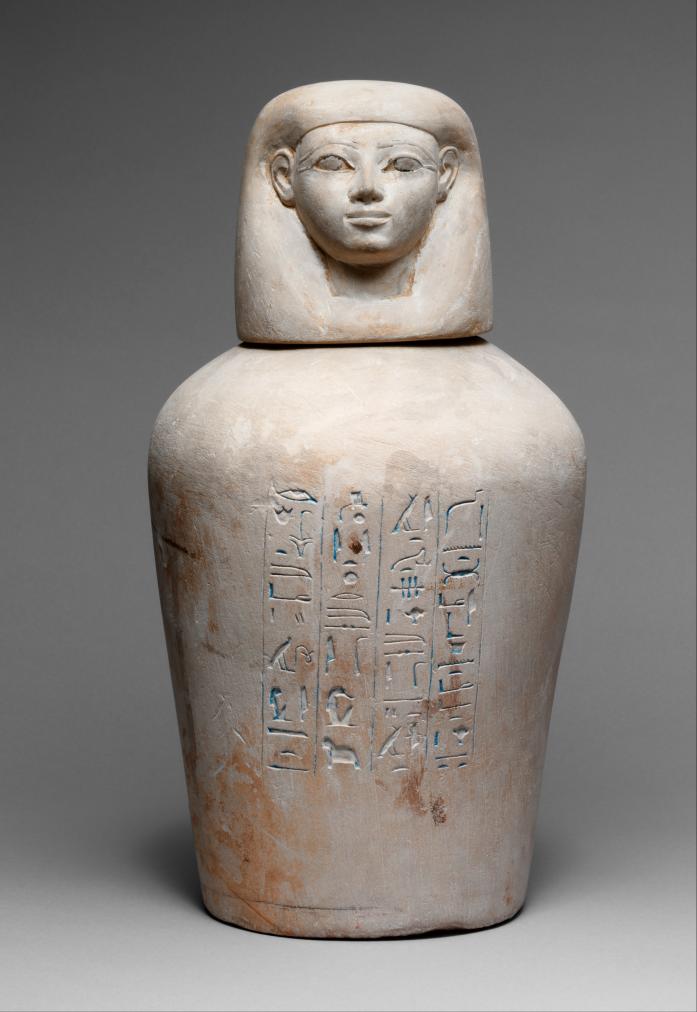

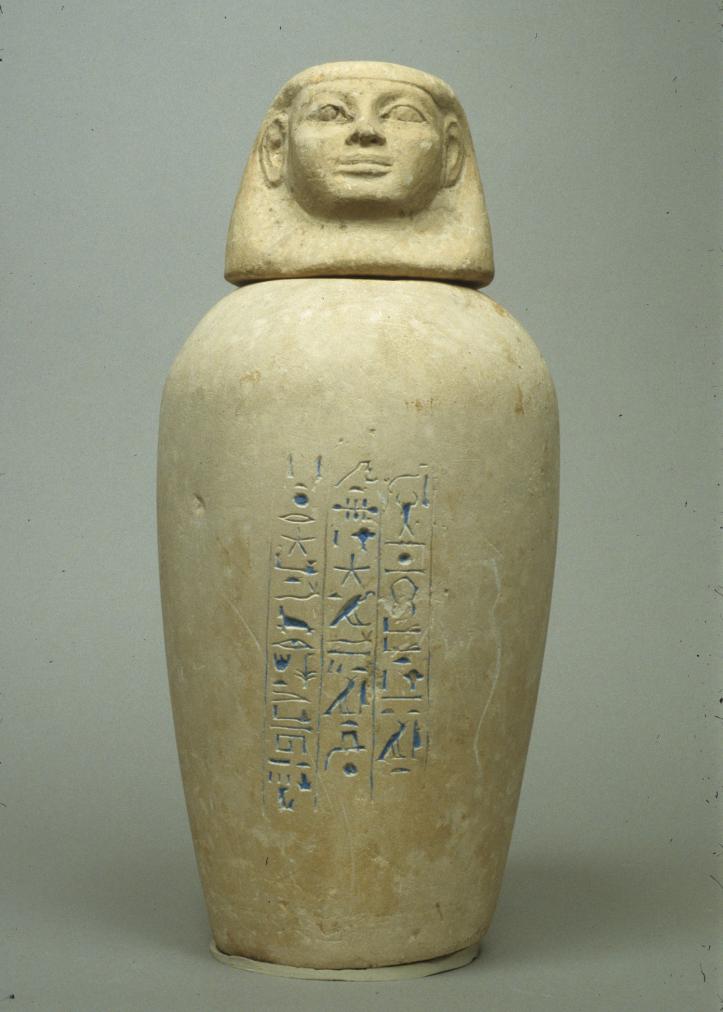

The contents of the tomb, including Canopic jars, a large assortment of gold jewelry, and a gold diadem inlayed with semi-precious stones, indicate that the tomb belonged to three wives of Thutmes III. Both his Cartouche, as well as Hatshepsut’s name and titles as queen are present on a number of stone vessels, broad collars, and a mirror. Hieroglyphic inscriptions on the canopic jars name the three women - Menhet, Menwi, and Merti - and state that they held the title Hmt-nswt “King’s wife”. Most scholars agree that the names are not of Egyptian origin and that the three wives were foreign, although the exact area of origin is still debated.

While Menhet, Menwi, and Merti do not appear anywhere else in the archaeological record and are not mentioned alongside the other wives of Thutmes III, the fact that they carried the title “King’s wife”, were buried with lavish gifts, and were given a tomb typical of 18th Dynasty queens is indicative of their royal status.

Noteworthy features:

The tomb belonged to the three foreign wives of Thutmes III, Menhet, Menwi, and Merti, and is typical of 18th Dynasty queen’s tombs. It was filled with lavish royal gifts, including a large collection of gold jewelry inlaid with semi-precious stones, gold leaf and silver mirrors, and an assortment of beautiful stone cosmetic vessels.

Site History

According to Christine Lilyquist, Wadi D-1 was most probably constructed and filled with funerary equipment prior to Hatshepsut’s proscription (no earlier than year 42 of Thutmes III’s reign). This is due to the fact that the pottery discovered in the tomb favors an early 18th Dynasty date, as well as the fact that a number of stone vessels and scarabs from the tomb contain the name and titles of Hatshepsut.

After the burial of the Menhet, Menwi, and Merti, the tomb lay undisturbed until August 1916, when it was discovered by locals from the West Bank and robbed of the majority of its contents.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Site Condition

Due to its position at the base of a water worn cleft, the tomb suffered substantial flooding damage. Water coming from the plateau would empty into the cleft before flowing down into the Wadi, bringing debris that deposited in the tomb corridor. Furthermore, humidity from rain water entering the corridor and water seepage through the bed of rock above the tomb caused large chunks of limestone to fall from the ceiling of the burial chamber. Parts of the burial chamber ceiling have also been blackened by smoke from robbers’ fires and bats.

Due to its distant location and dangerous entry, the tomb is not open for public visitation.

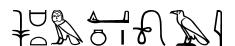

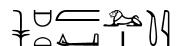

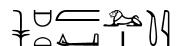

Hieroglyphs

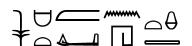

Queen Menhet

The King's wife, Menhet

Hmt-nswt mnhtA

The King's wife, Menhet

Hmt-nswt mnhtA

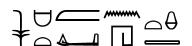

Queen Menwi

The King's wife, Menwi

Hmt-nswt mnw-wAi

The King's wife, Menwi

Hmt-nswt mnw-wAi

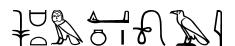

Queen Merti

The King's wife, Merti

Hmt-nswt mrti

The King's wife, Merti

Hmt-nswt mrti

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Latest Discovery in Wadi C (2022)

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

Bibliography

Carter, Howard. A Tomb prepared from Queen Hatshepsut and other Recent Discoveries at Thebes. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 4 no. 2/3 (1917): 107-118.

Lilyquist, Christine with contributions by James E. Hoch and A.J. Peden. The Tomb of Three Foreign Wives of Tuthmosis III. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

Lilyquist, Christine. The Tomb of Tuthmosis III's Foreign Wives: A Survey of its Architectural Type, Contents, and Foreign Connections. In: Christopher J. Eyre (ed.). Proceedings 7th International. Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3-9 September 1995. Louvain: Peeters, 1998: 677-681.

Redford, Donald B. The Wars in Syria and Palestine of Thutmose III. In B. Halpern, M. H. E. Weippert, TH. P. J. van den Hout, and I. Winter (Eds.), Culture and History of the Ancient Near East, Volume 16. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Scott, Nora E. Egyptian Jewelry. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1964.

Winlock, Herbert E. The Treasure of Three Egyptian Princesses. Publications of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art, 10. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1948.