QV 55

Prince Amenherkhepshef

Entryway A

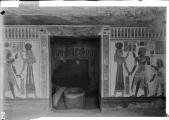

See entire tombAfter the descending stairs, a long entryway Ramp with an Overhang leads into the tomb. This ramp now has modern cement Steps. The Ceiling Recess at the end of the overhang has the old Italian Archaeological expedition sign with the name of Amenhekhepshef and the tomb number.

Gate B

See entire tombThe door jamb has a slot cut at the top for a lintel beam and has been reconstructed in concrete. The thicknesses are decorated with images of winged Maat figures.

Porter and Moss designation:

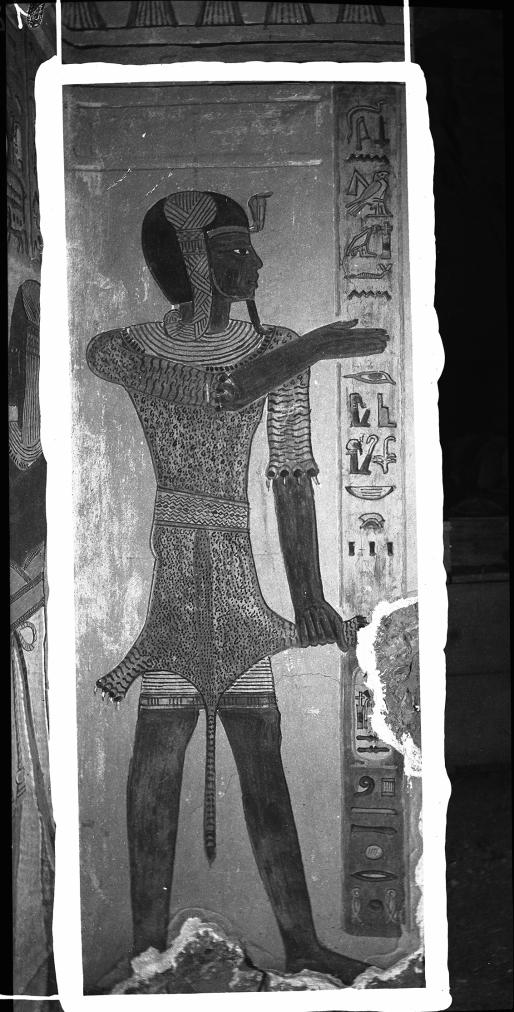

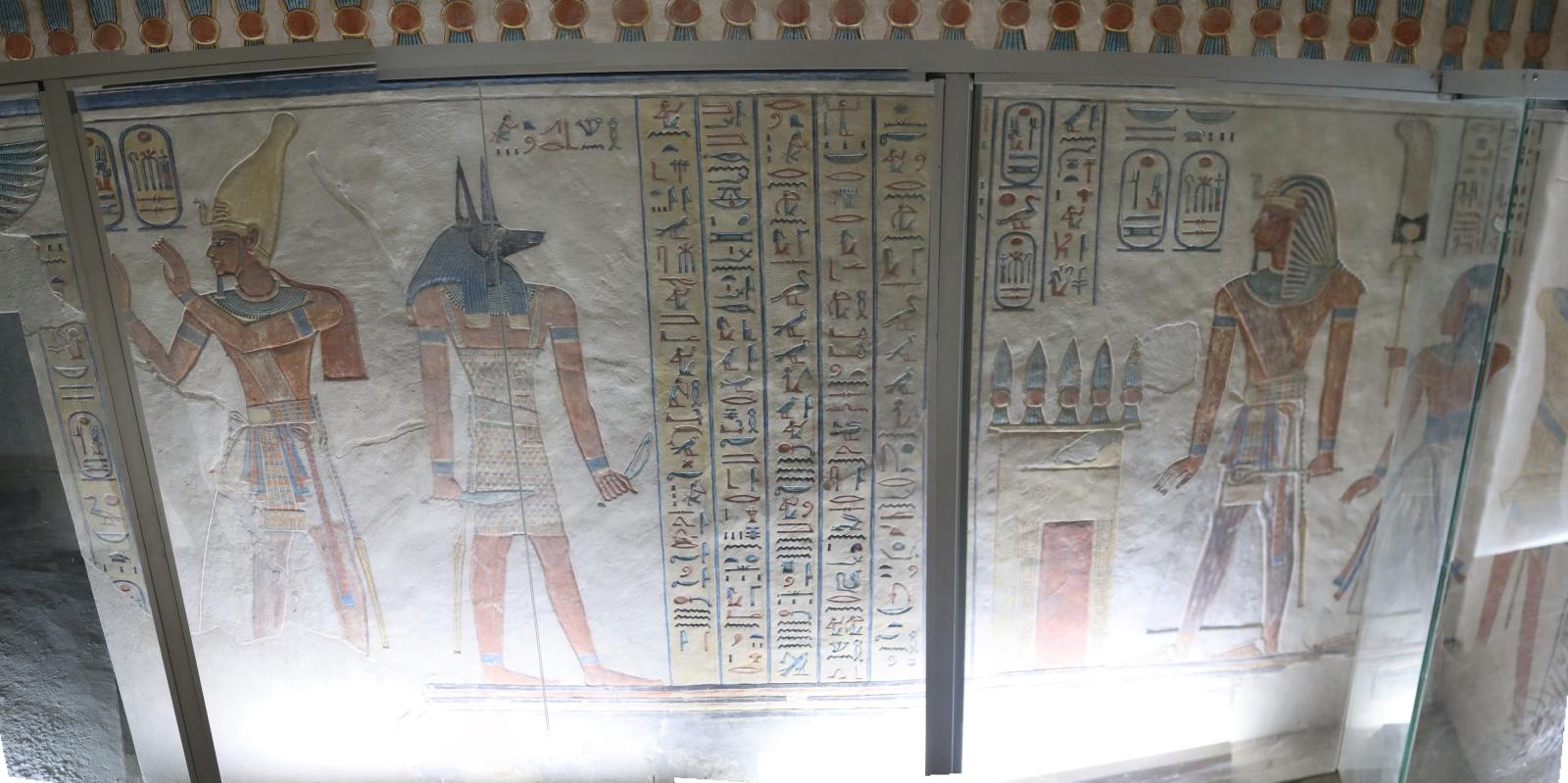

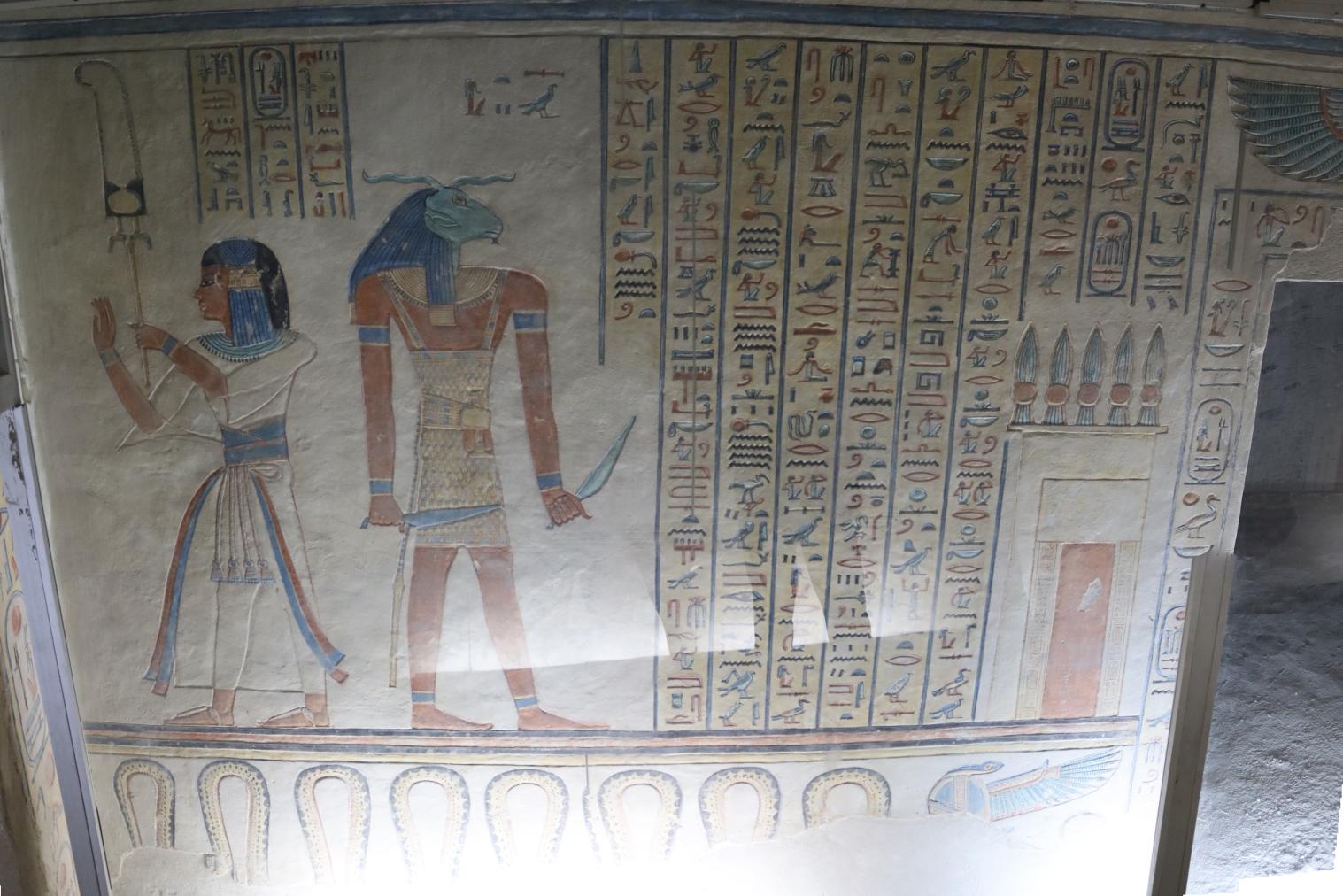

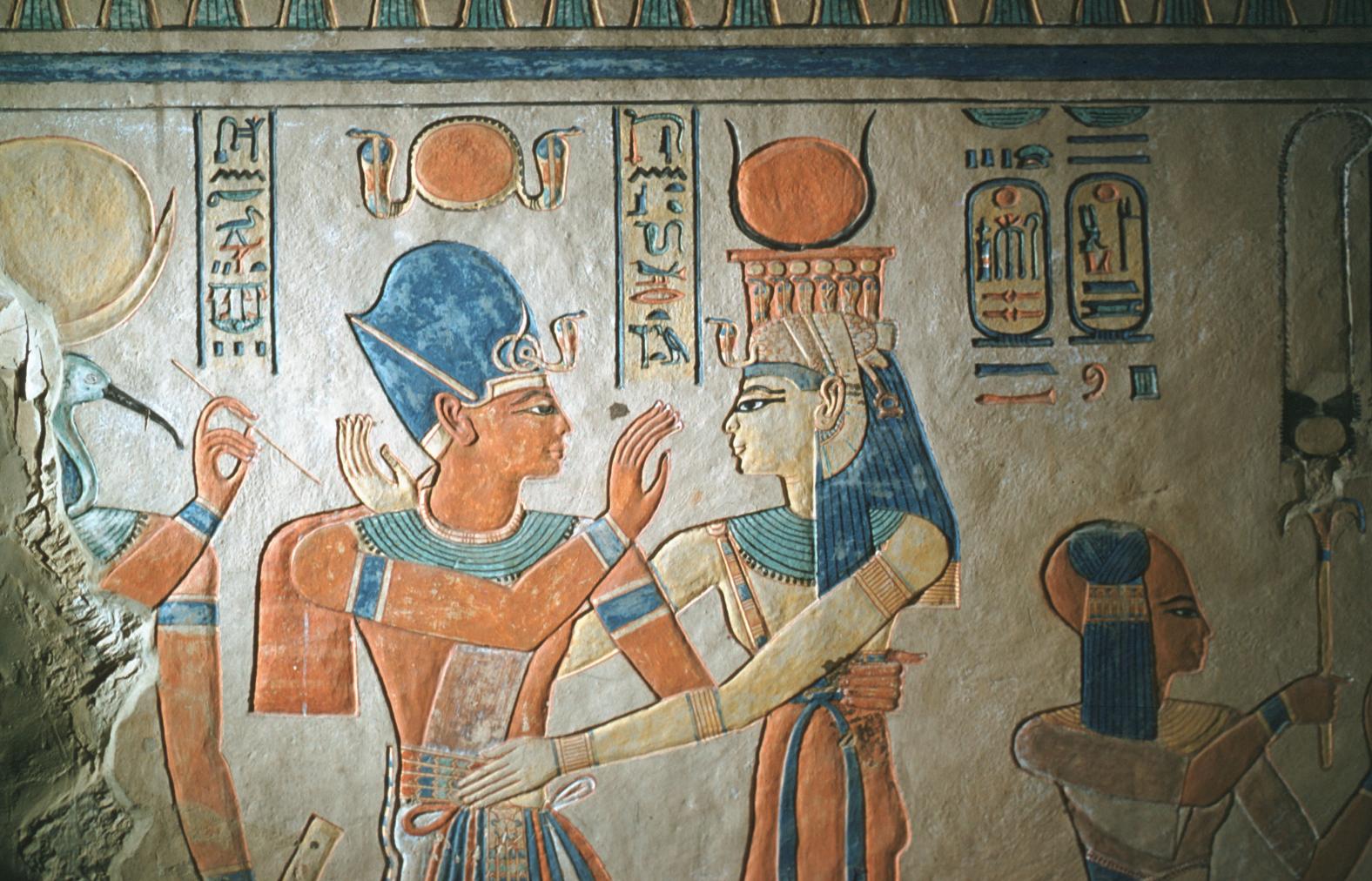

Chamber B

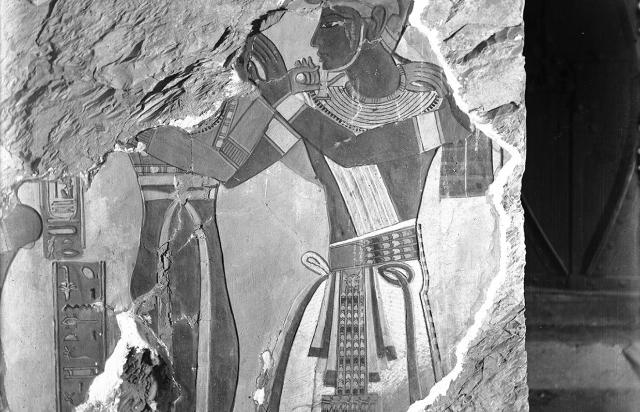

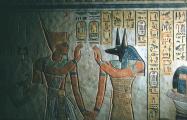

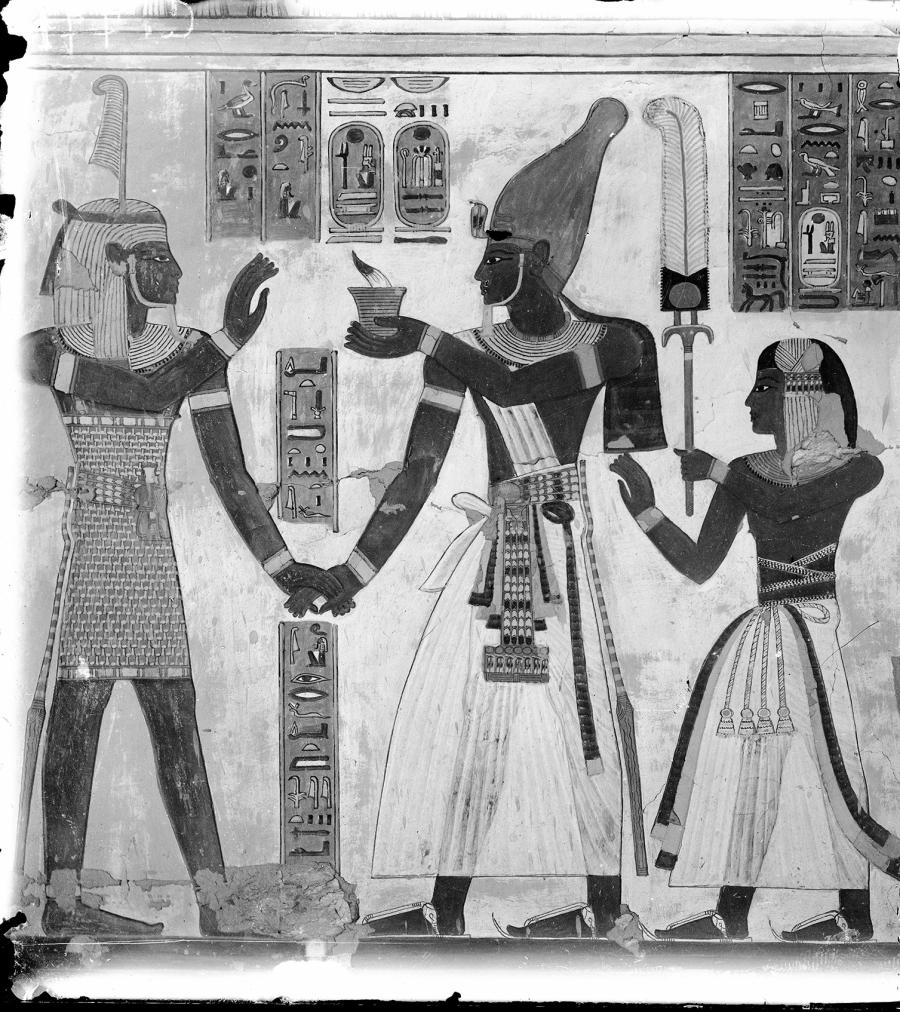

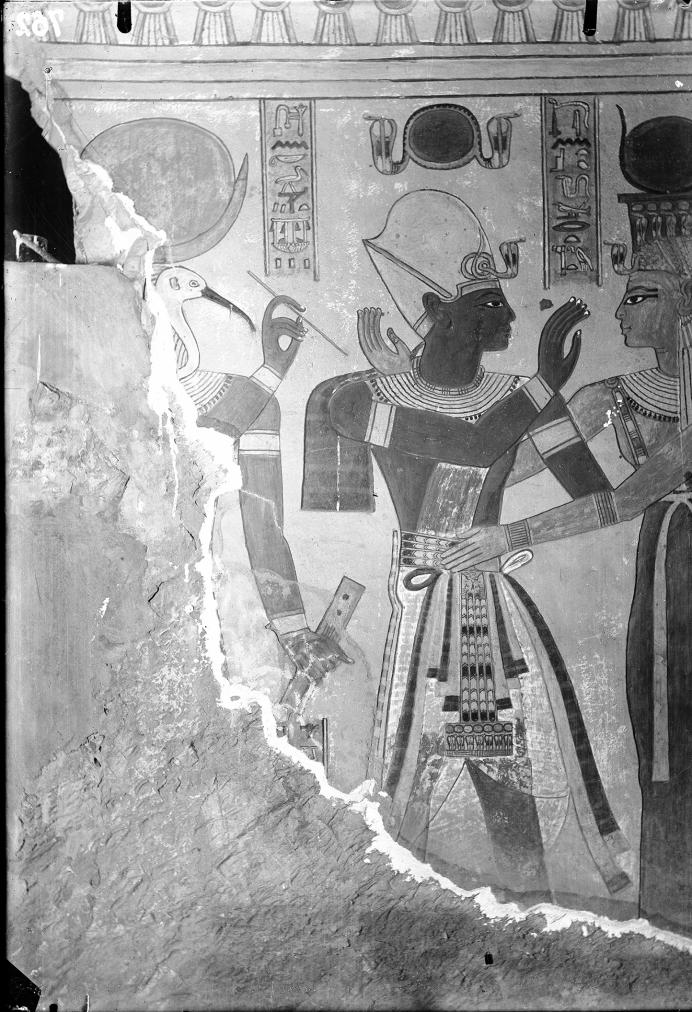

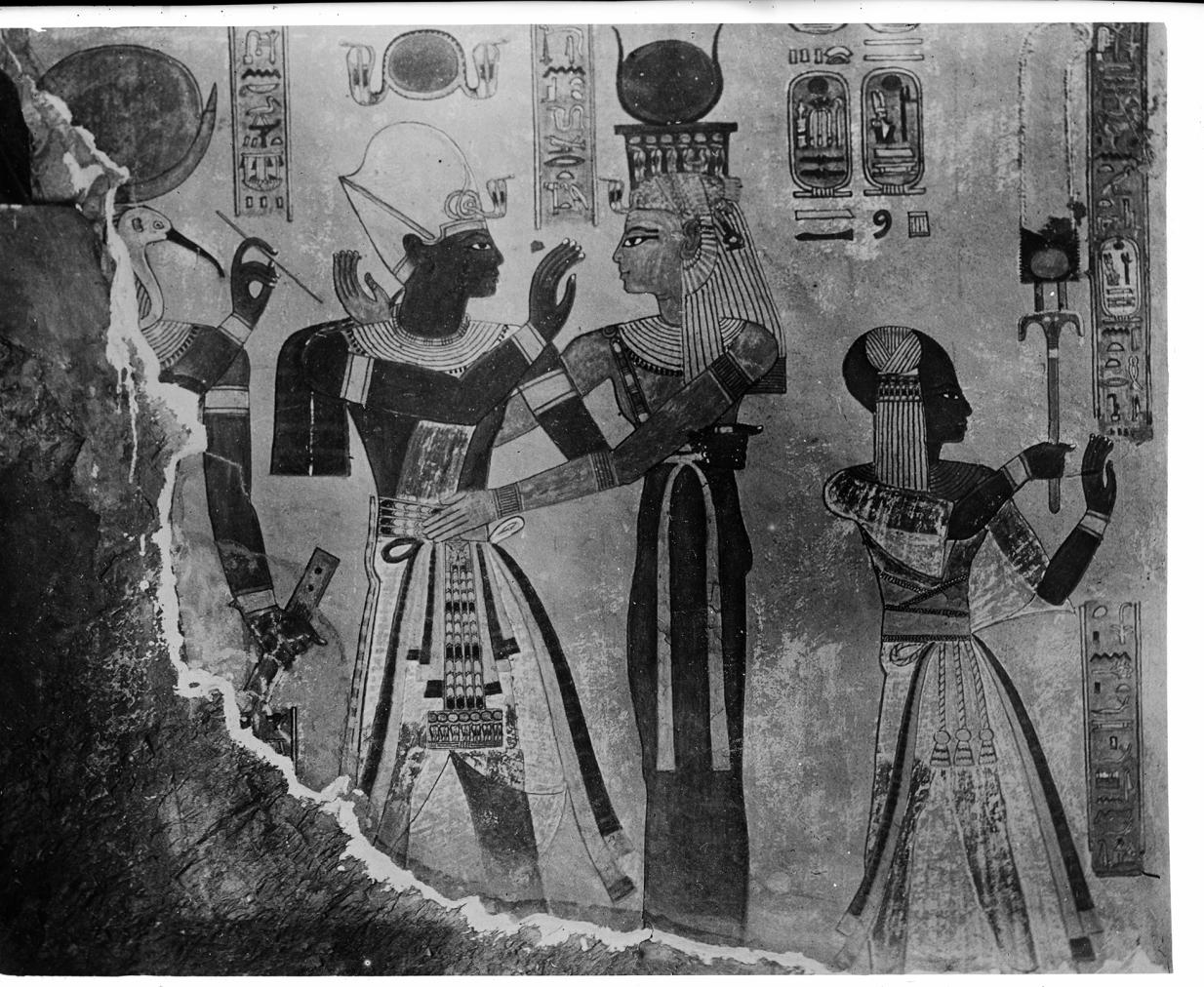

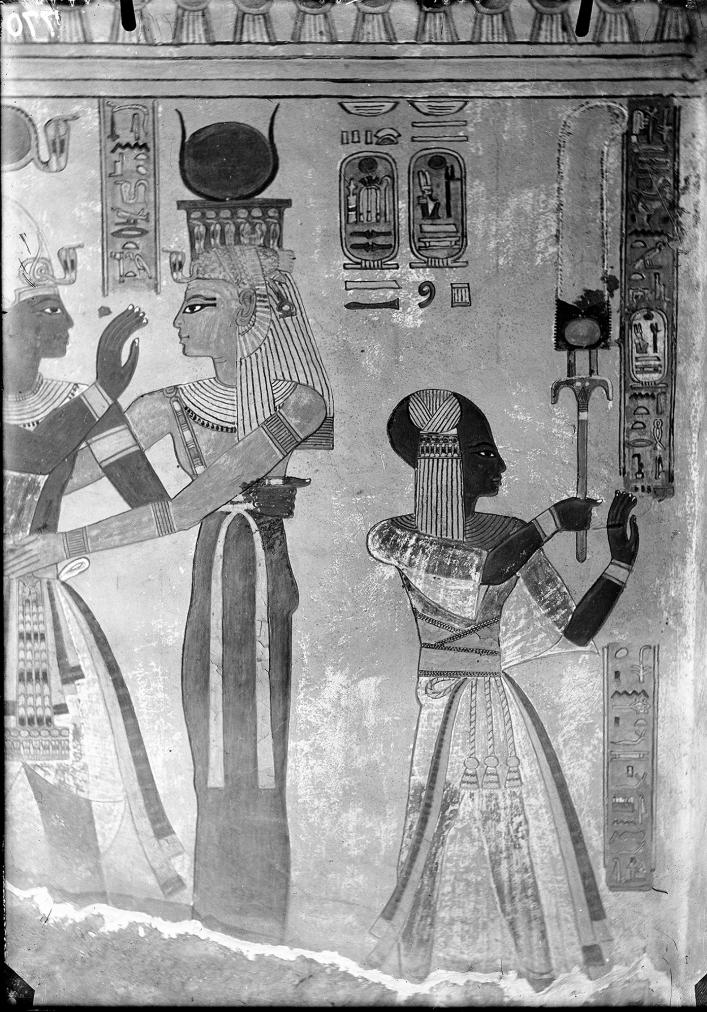

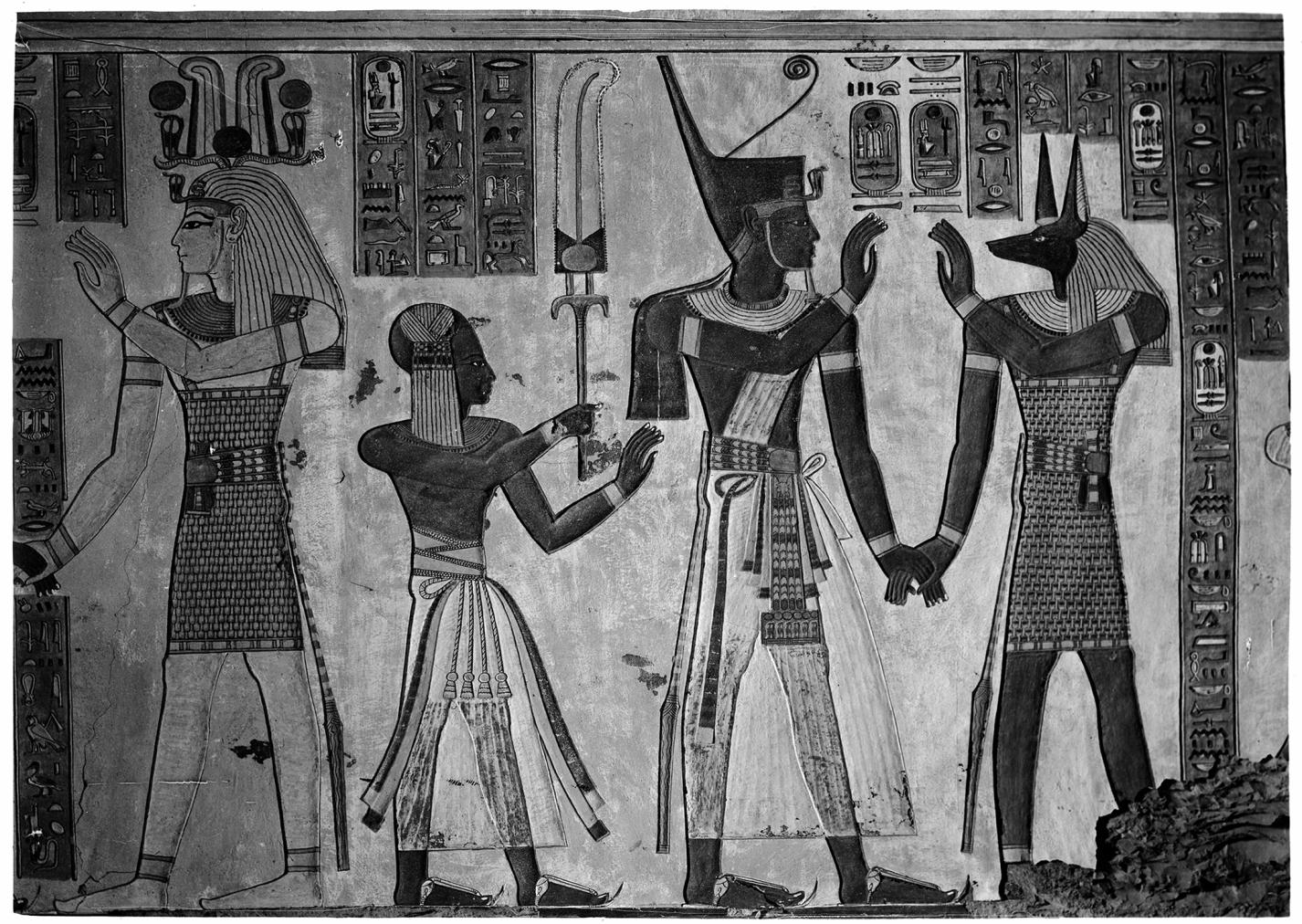

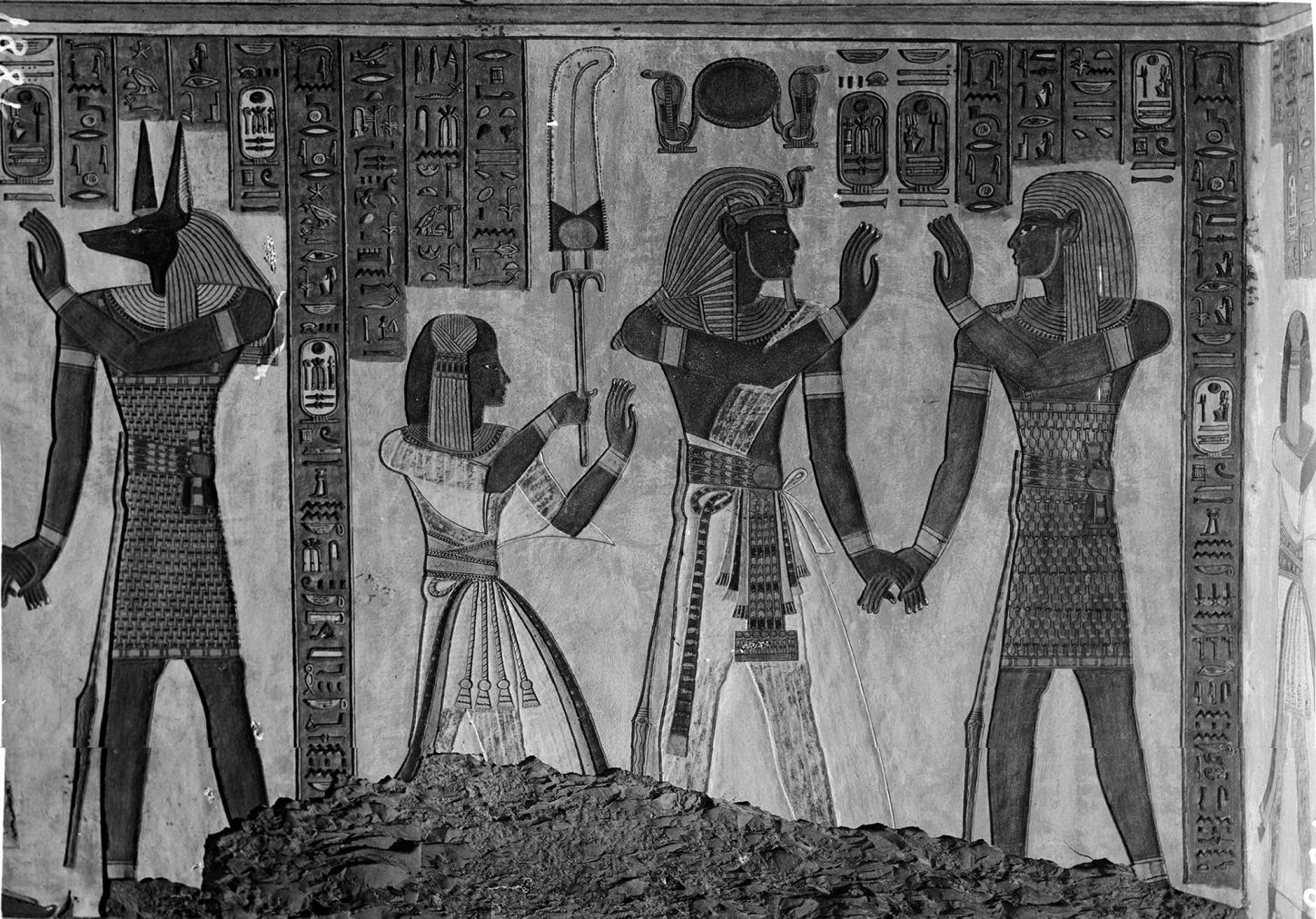

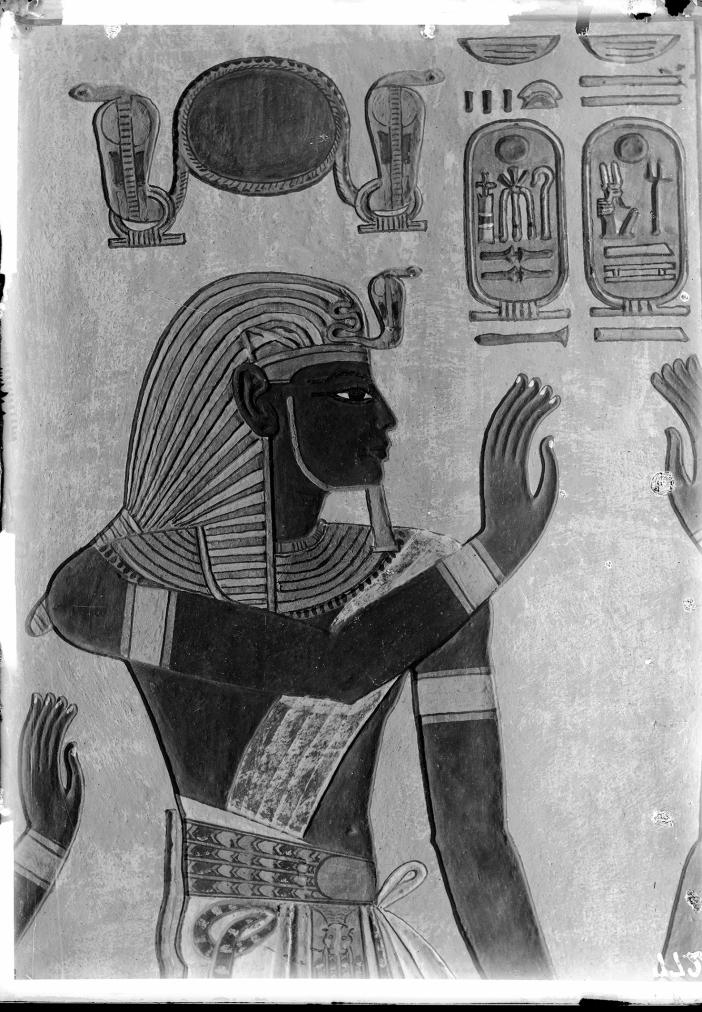

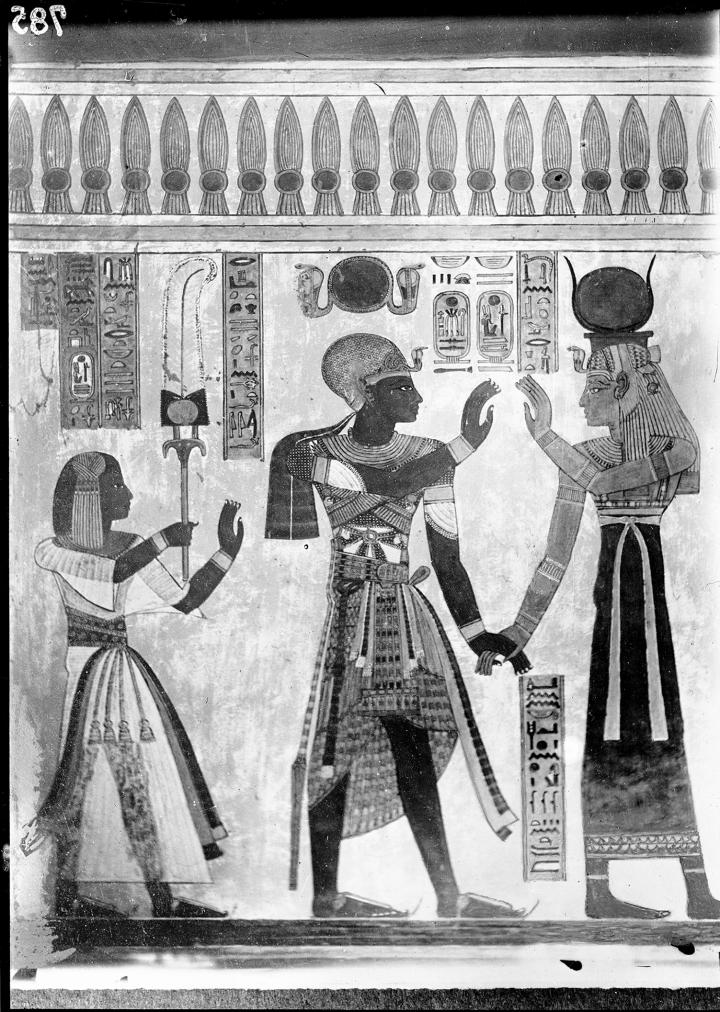

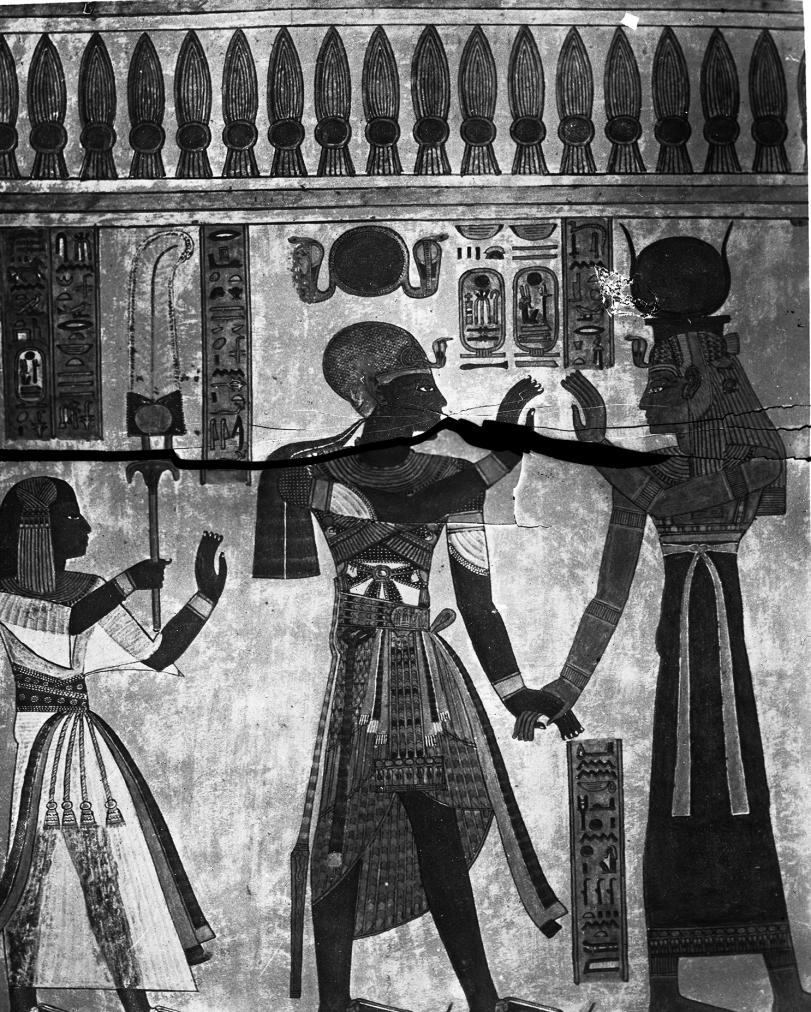

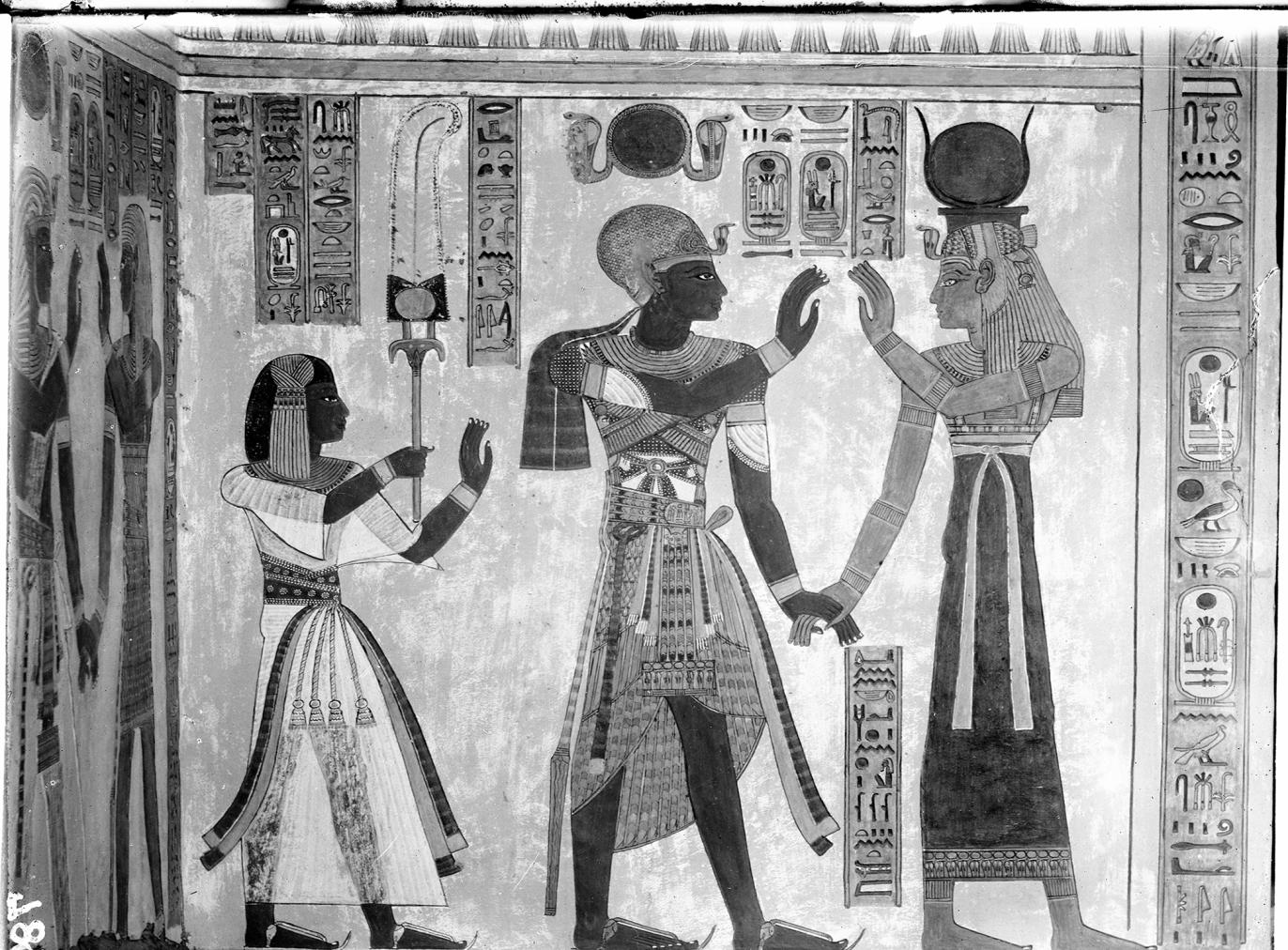

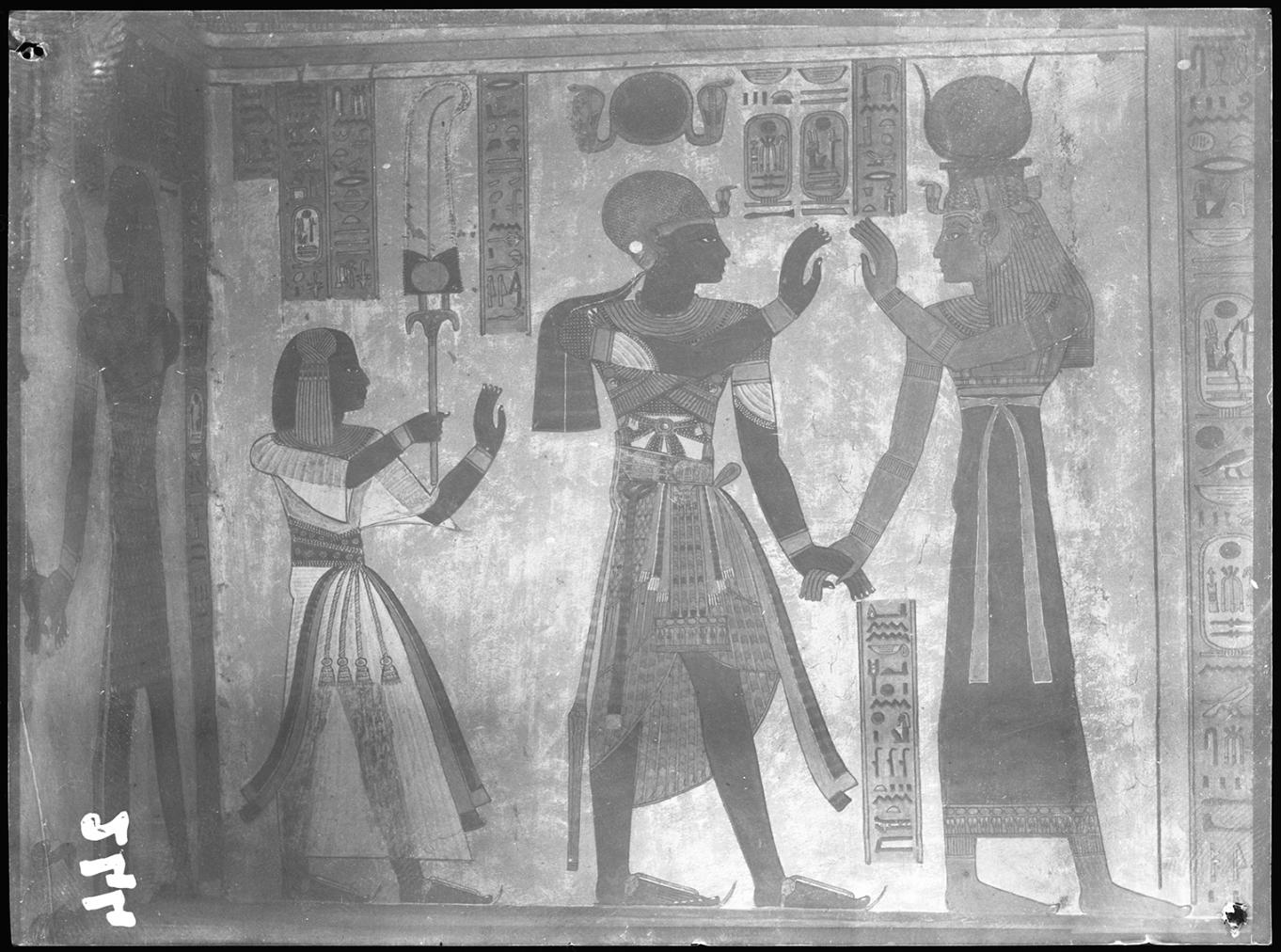

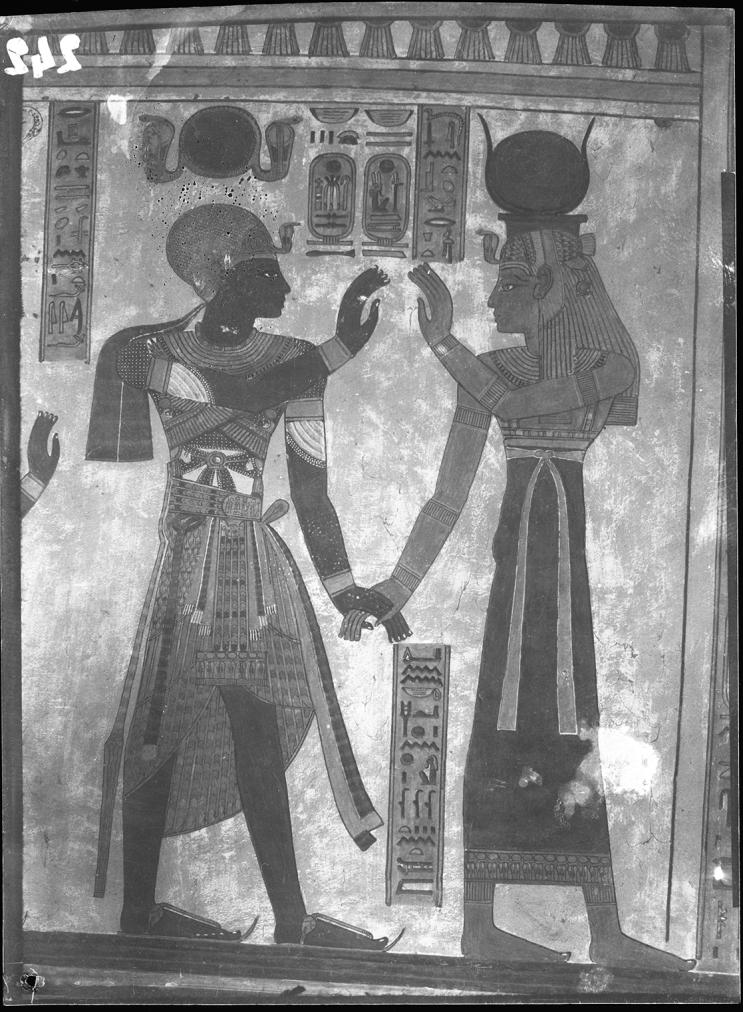

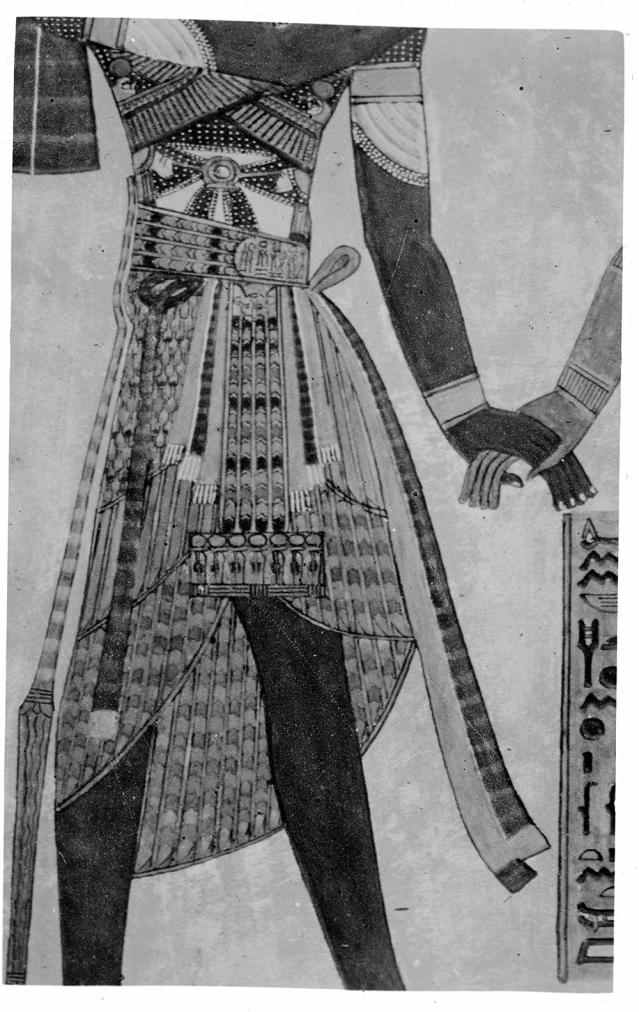

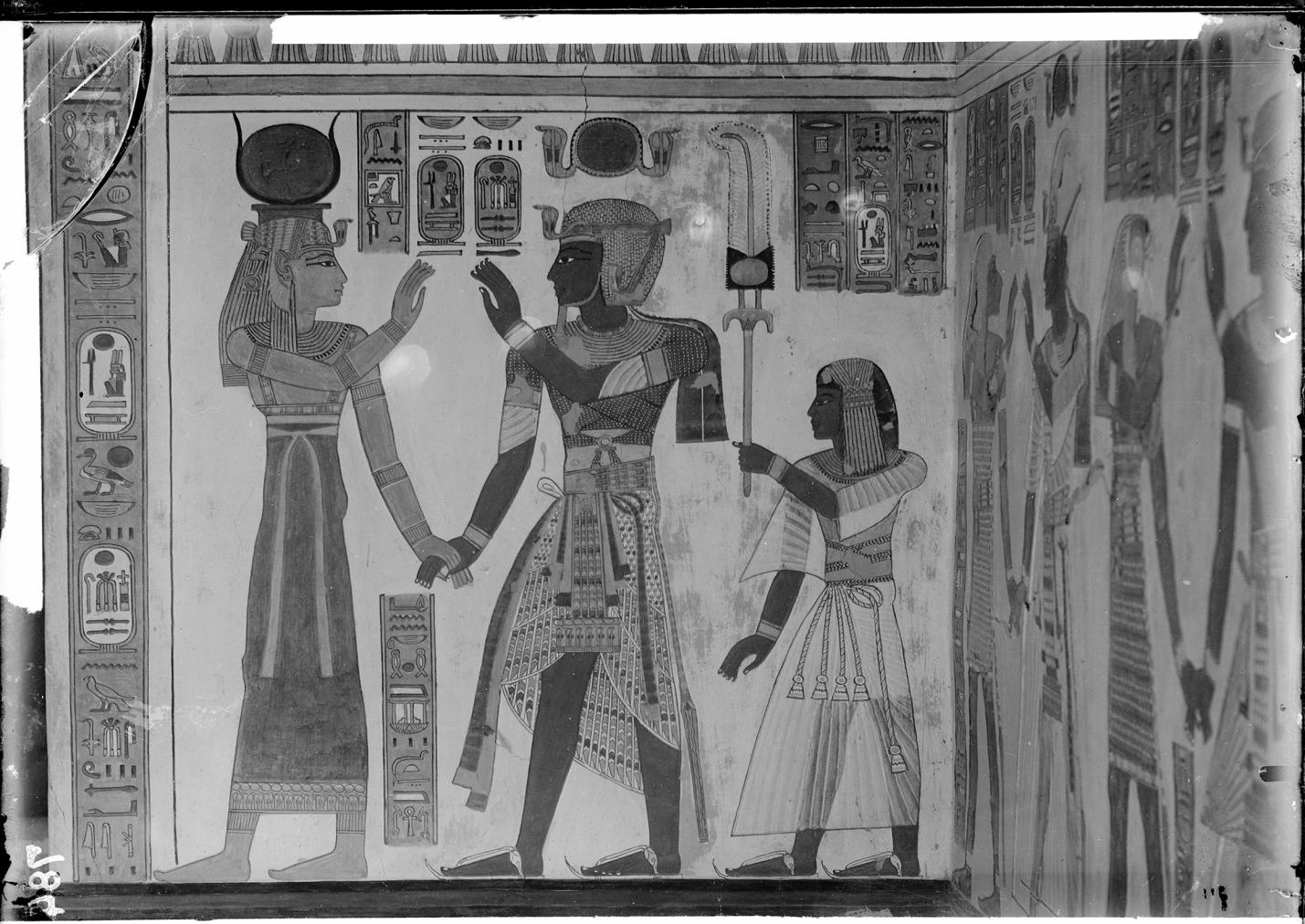

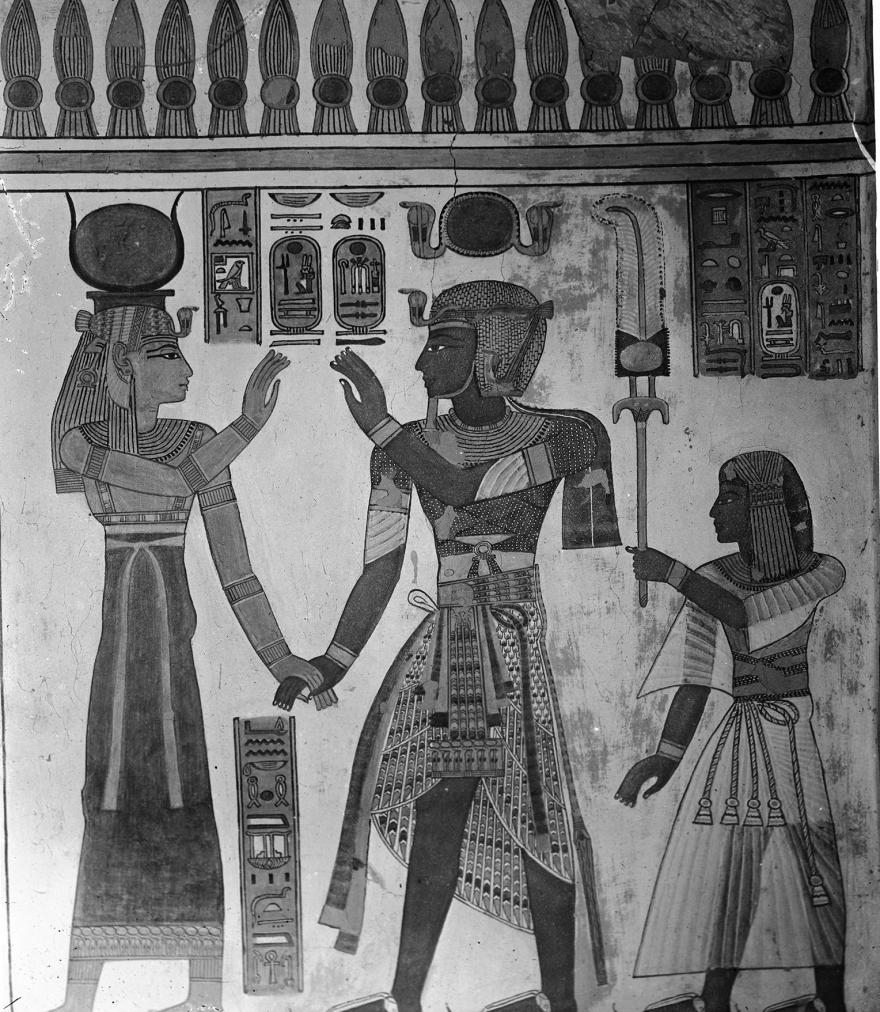

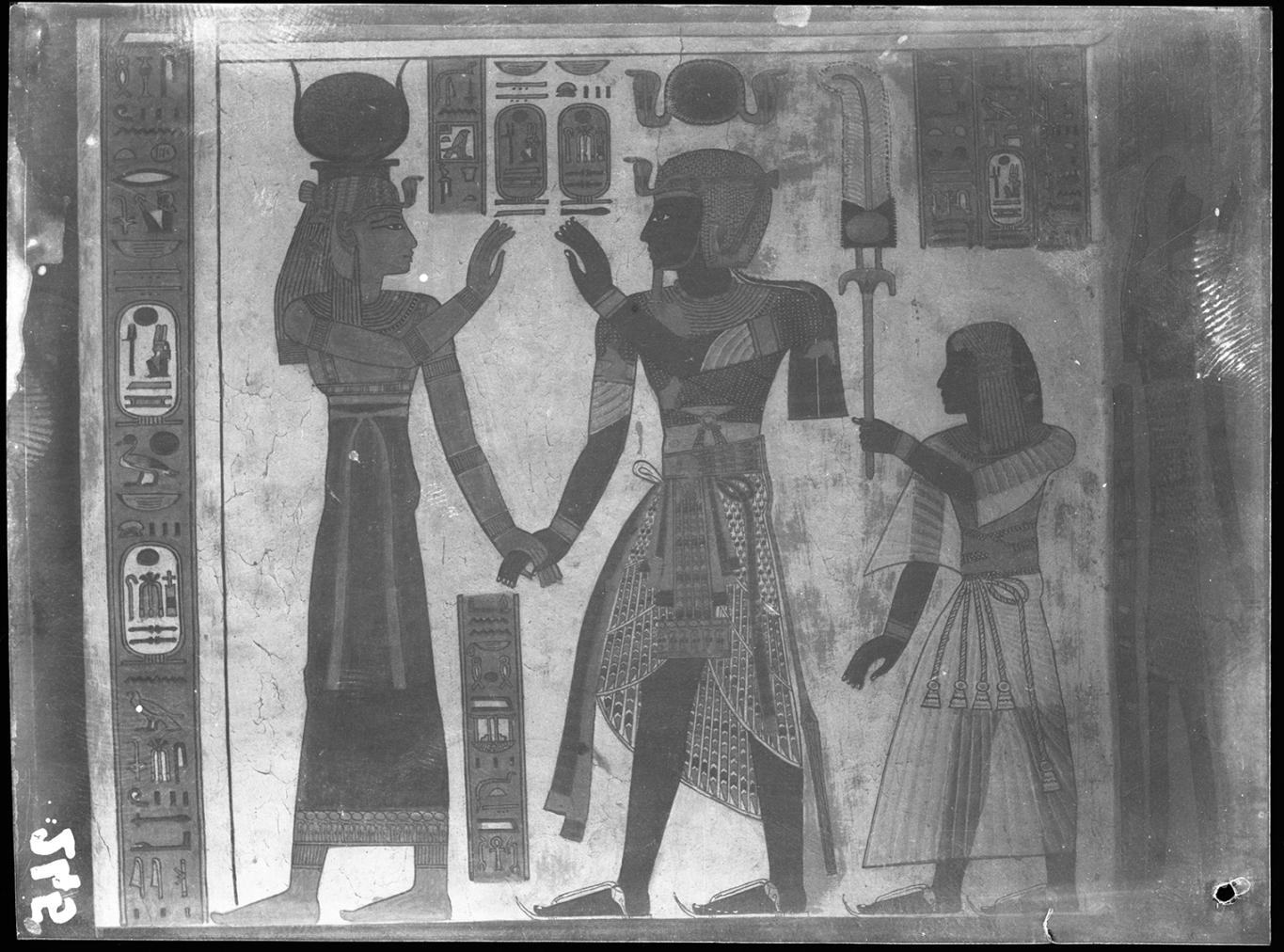

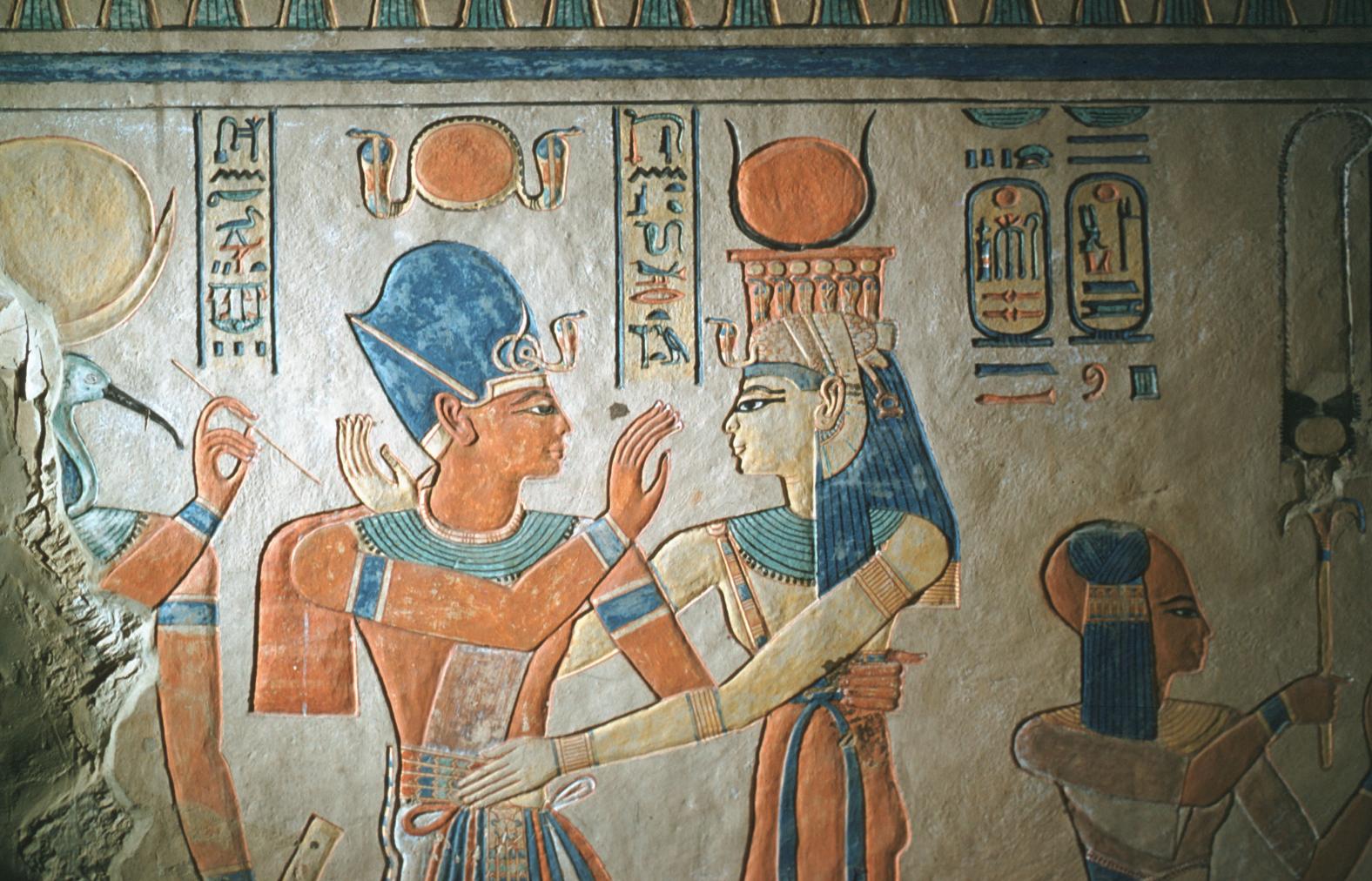

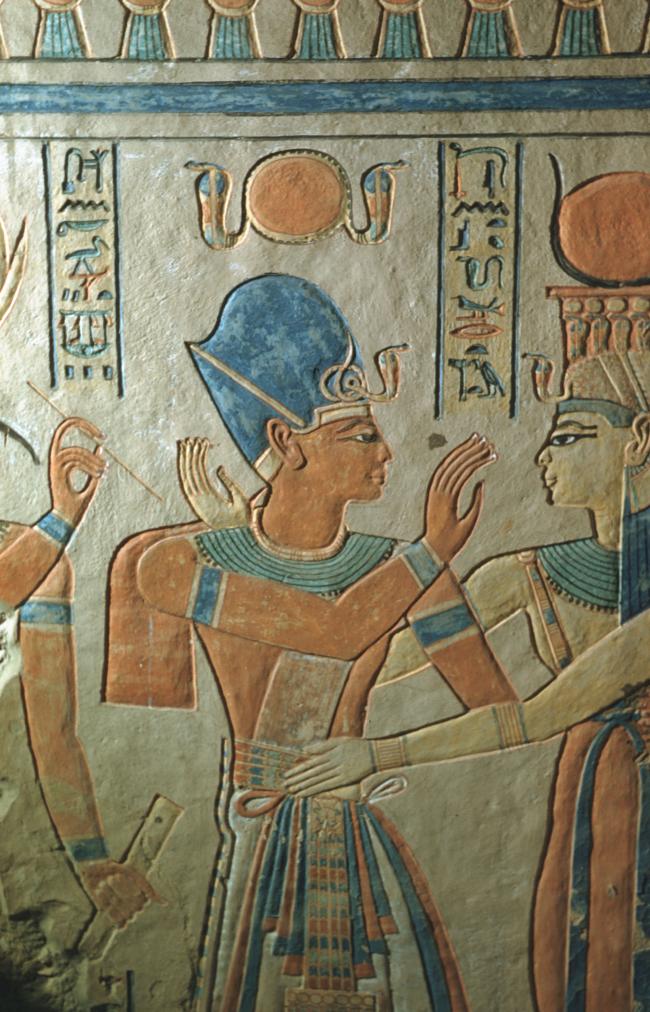

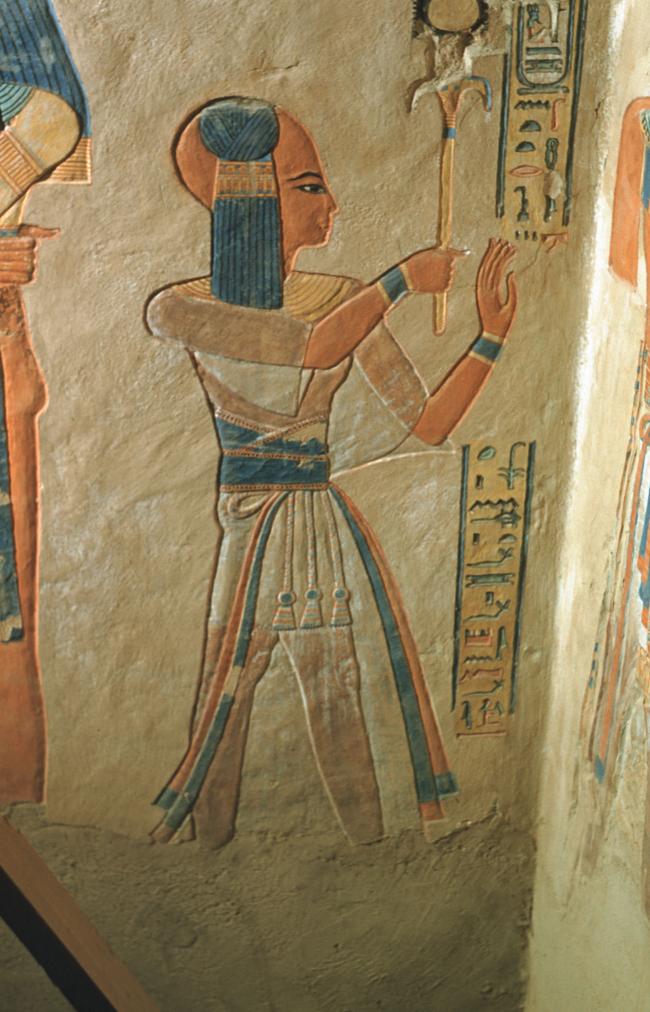

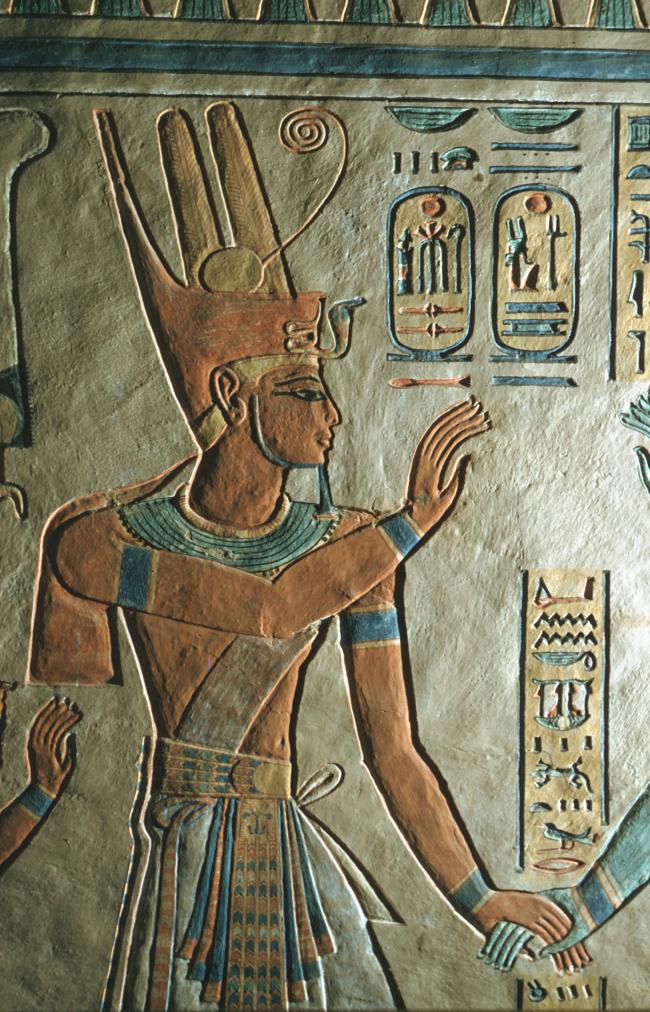

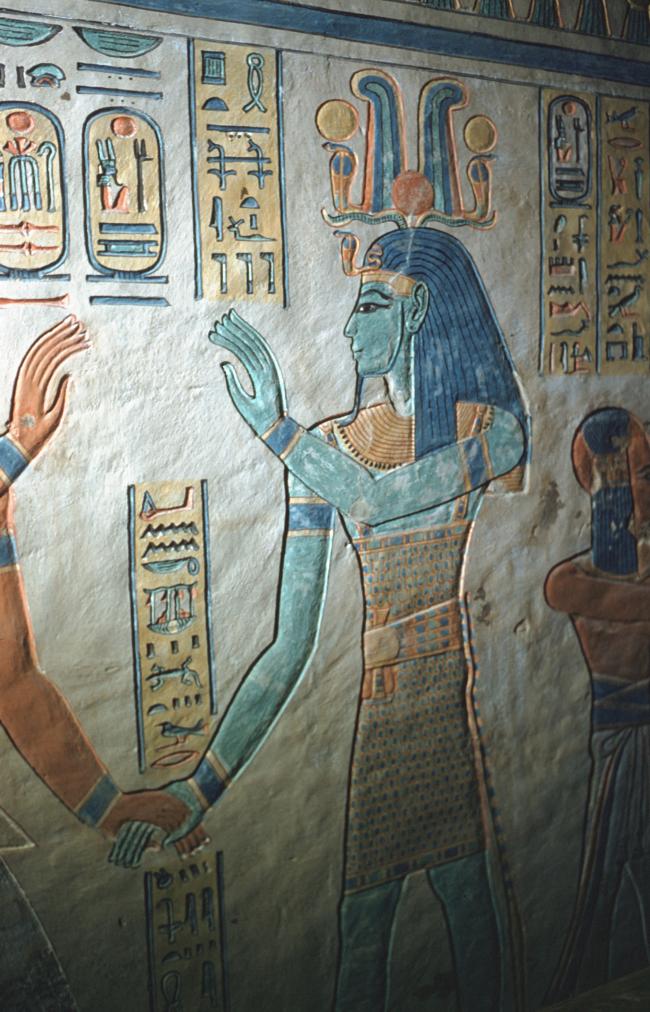

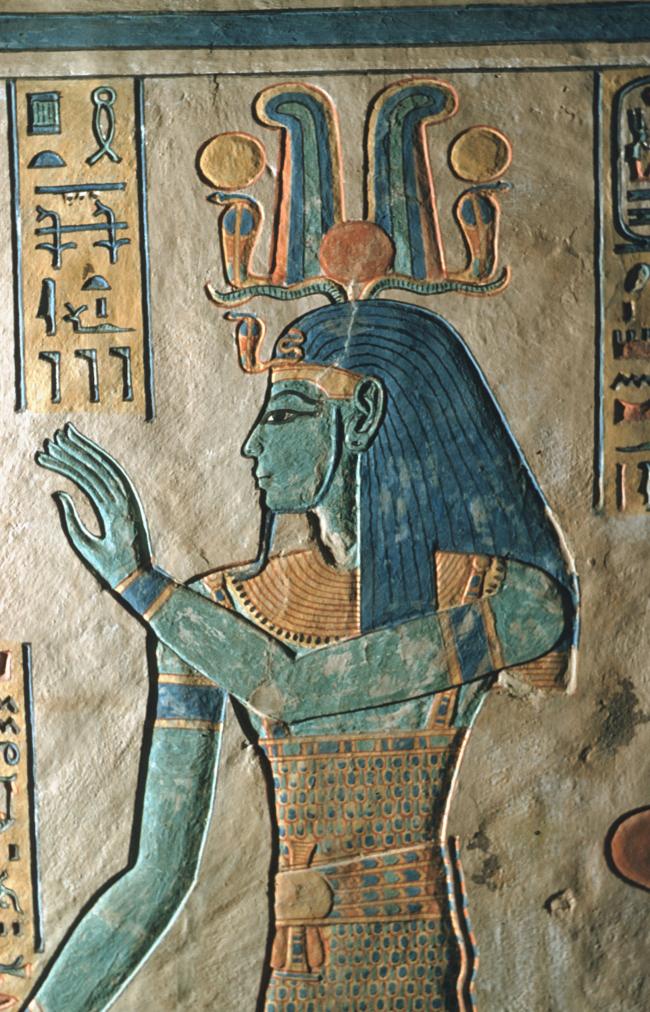

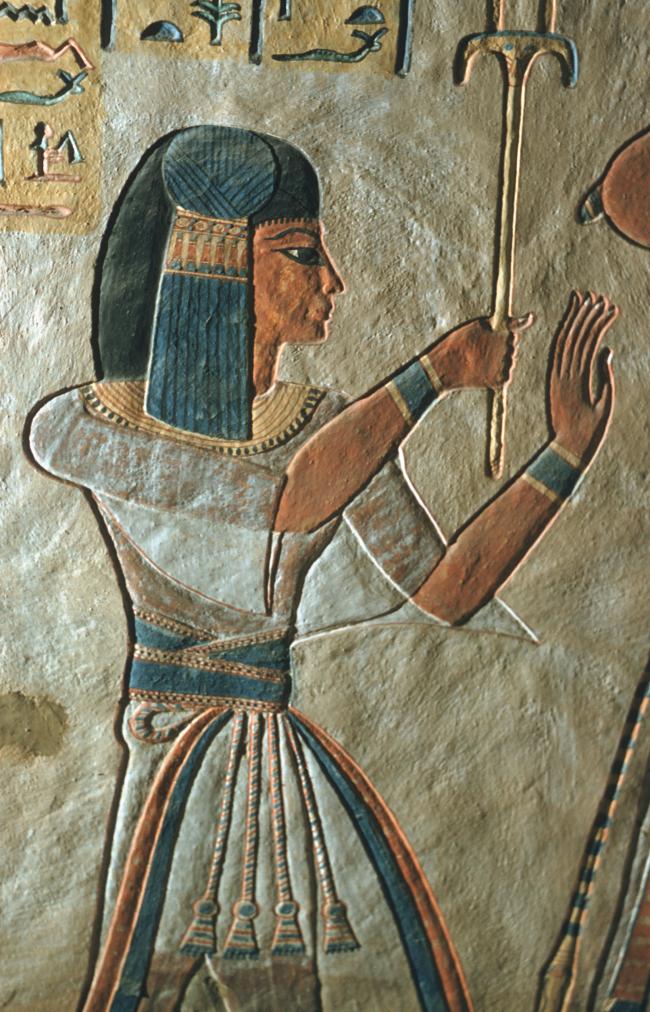

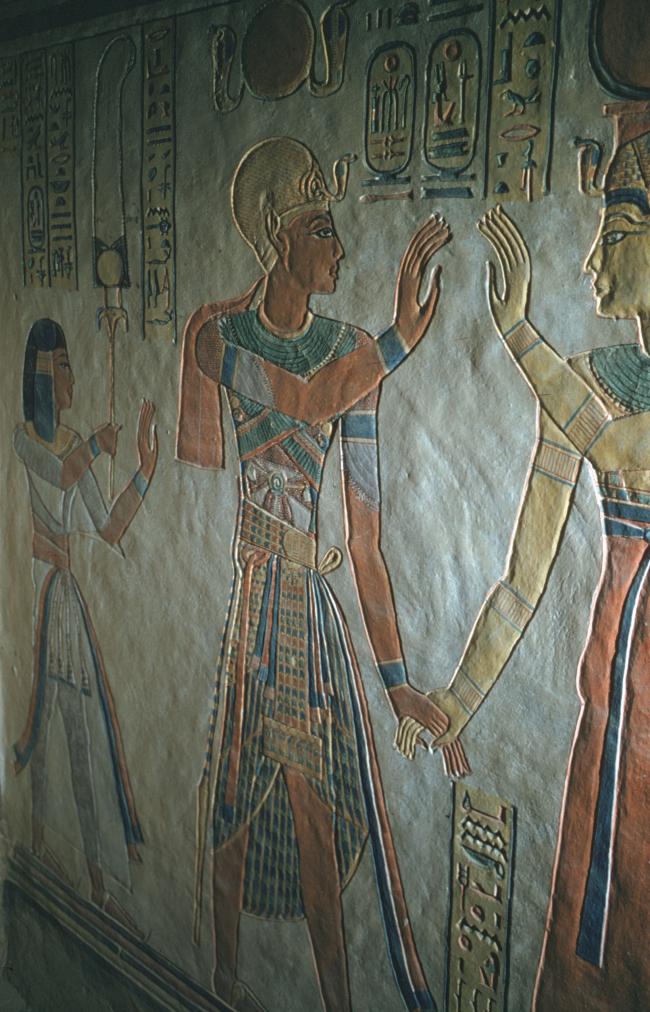

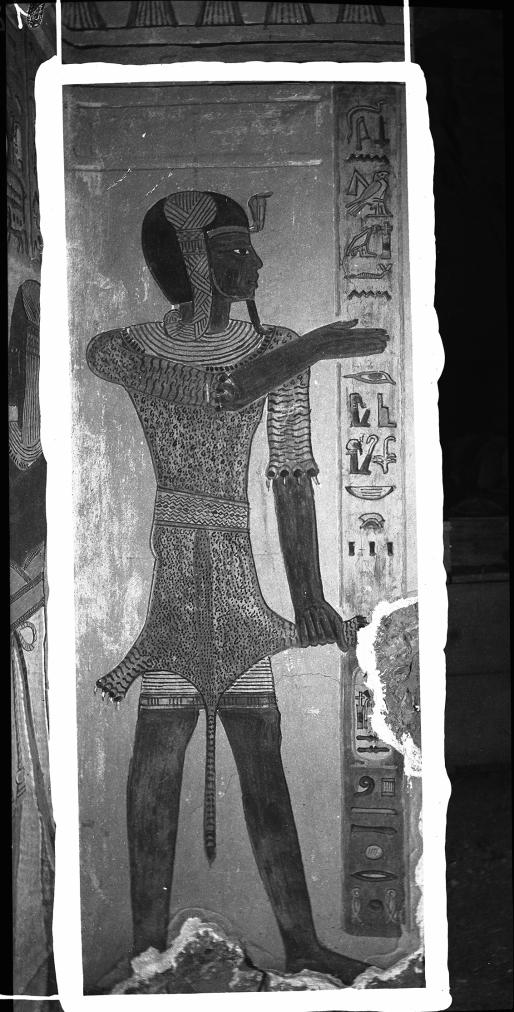

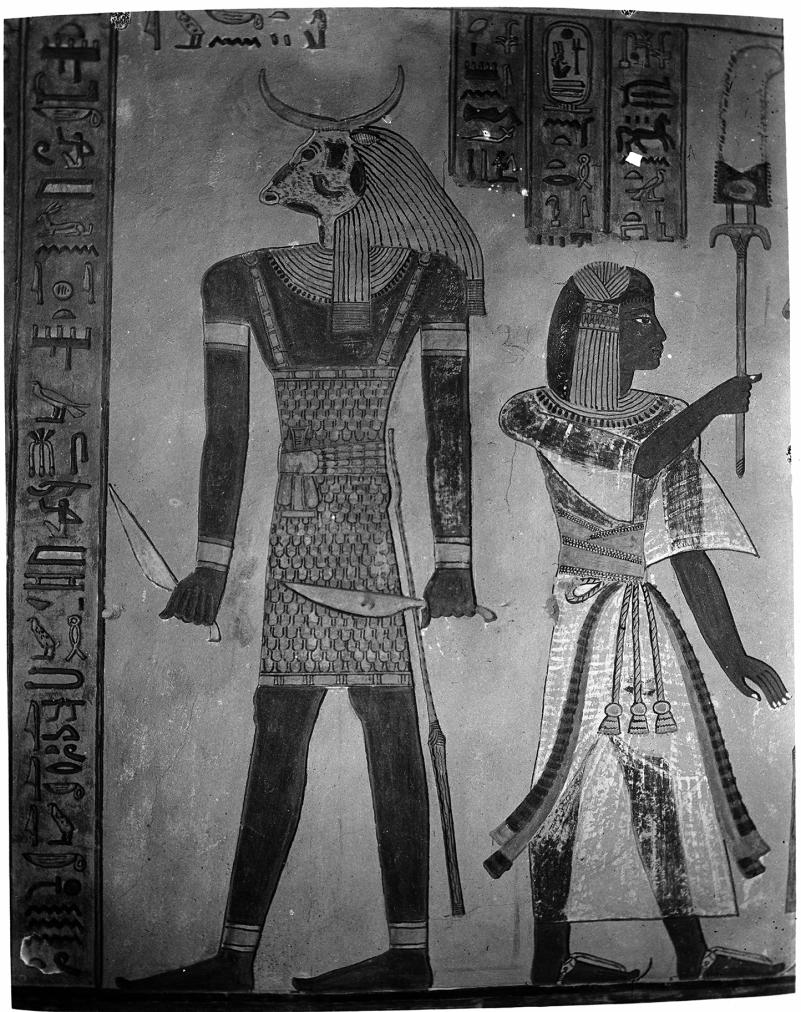

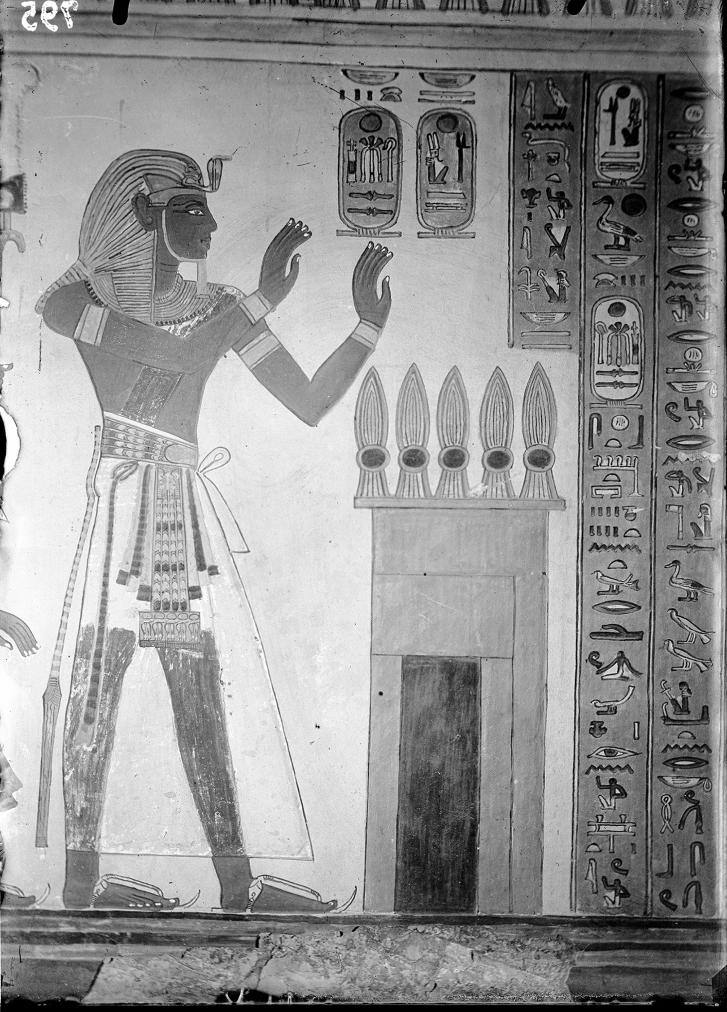

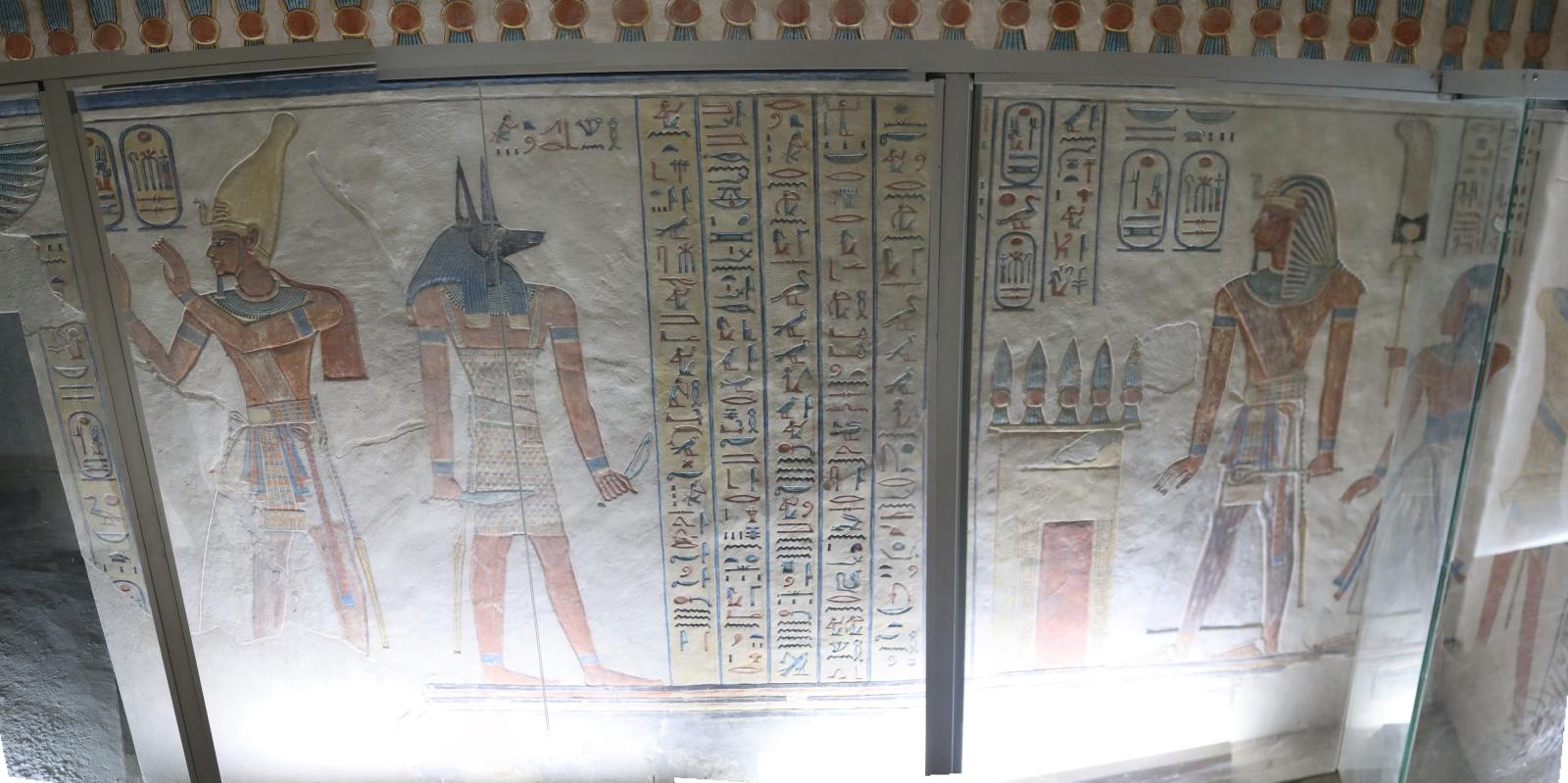

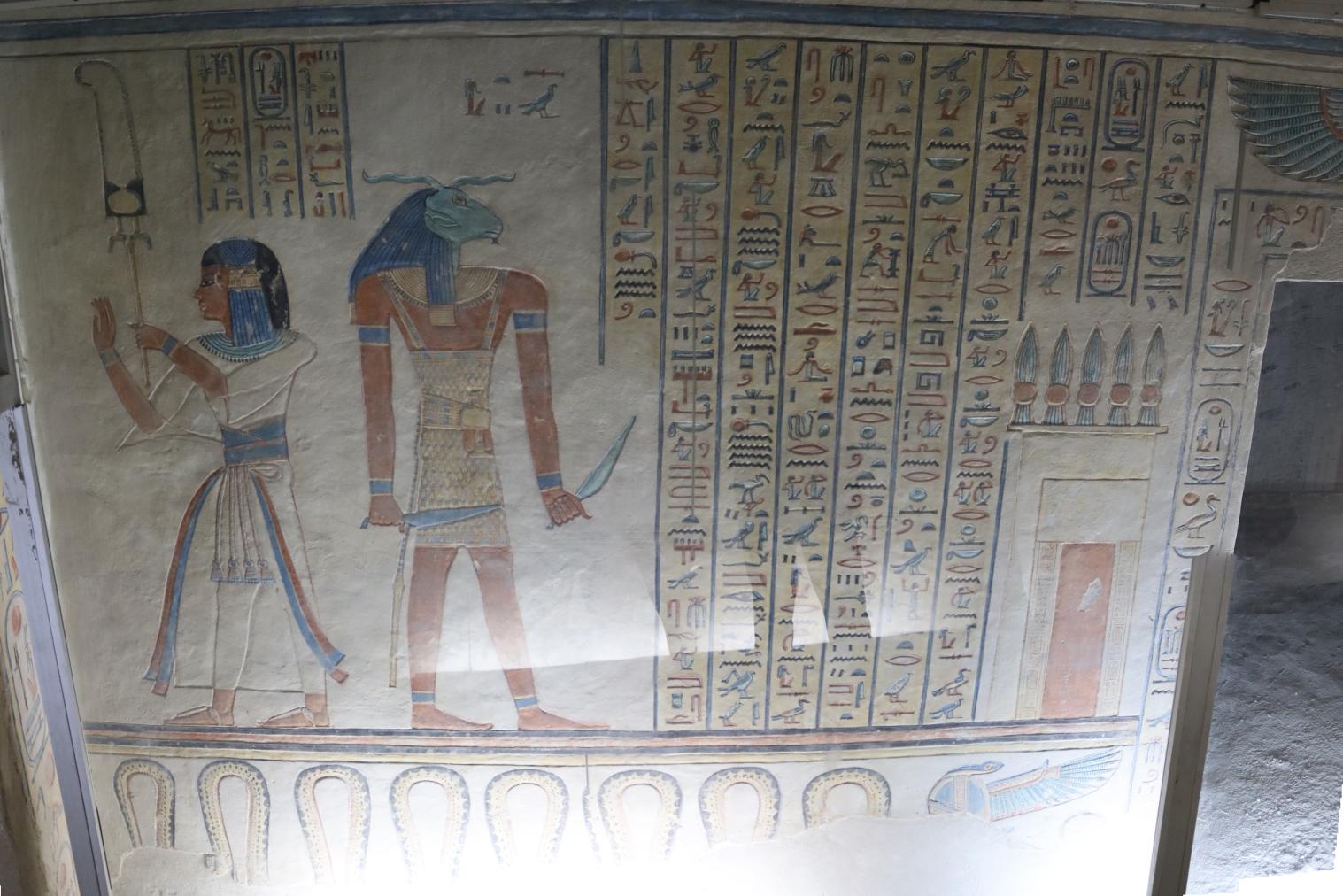

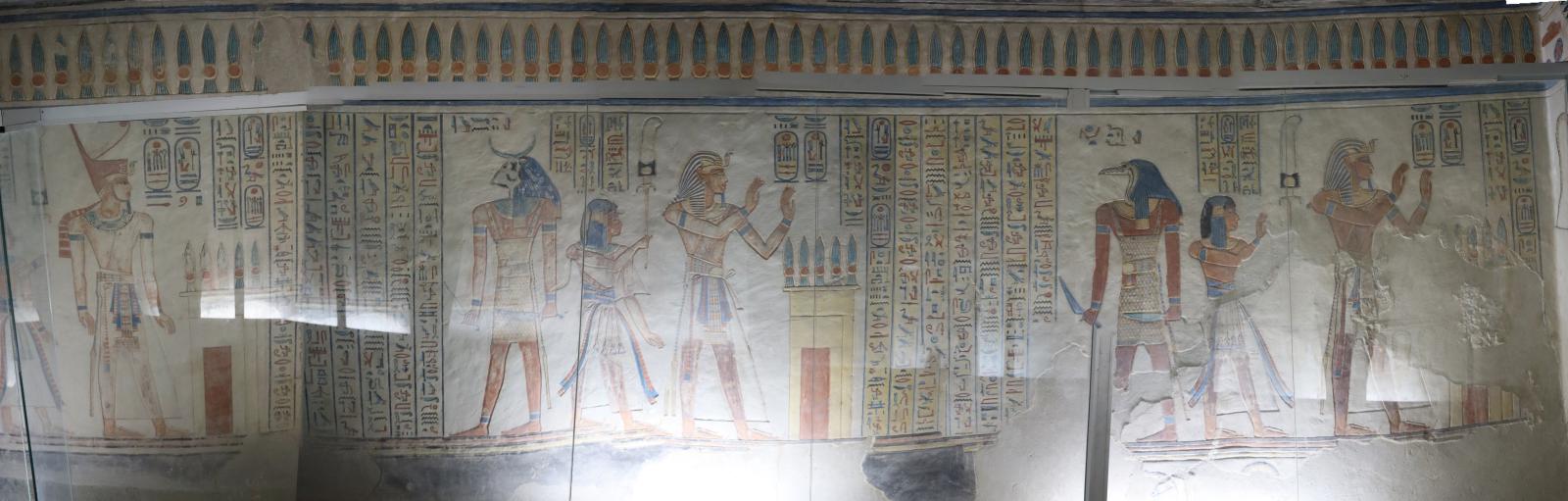

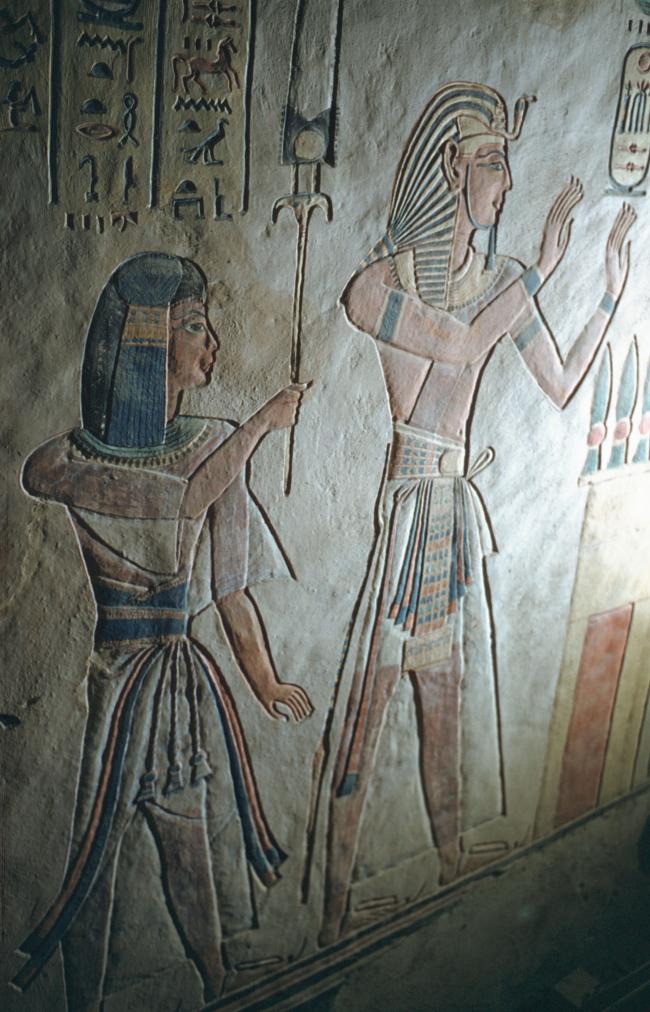

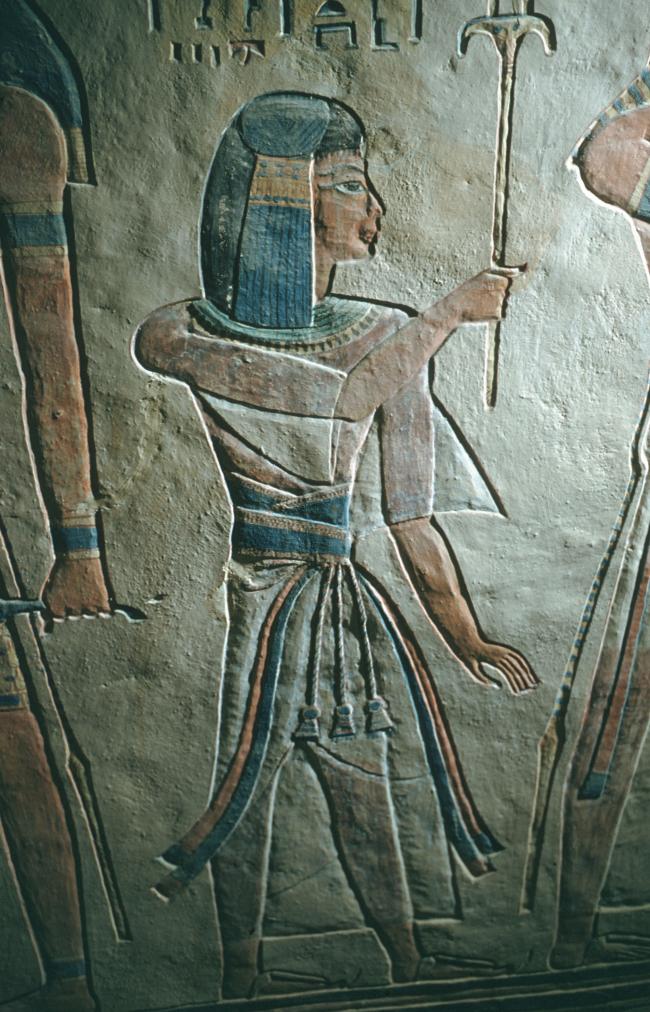

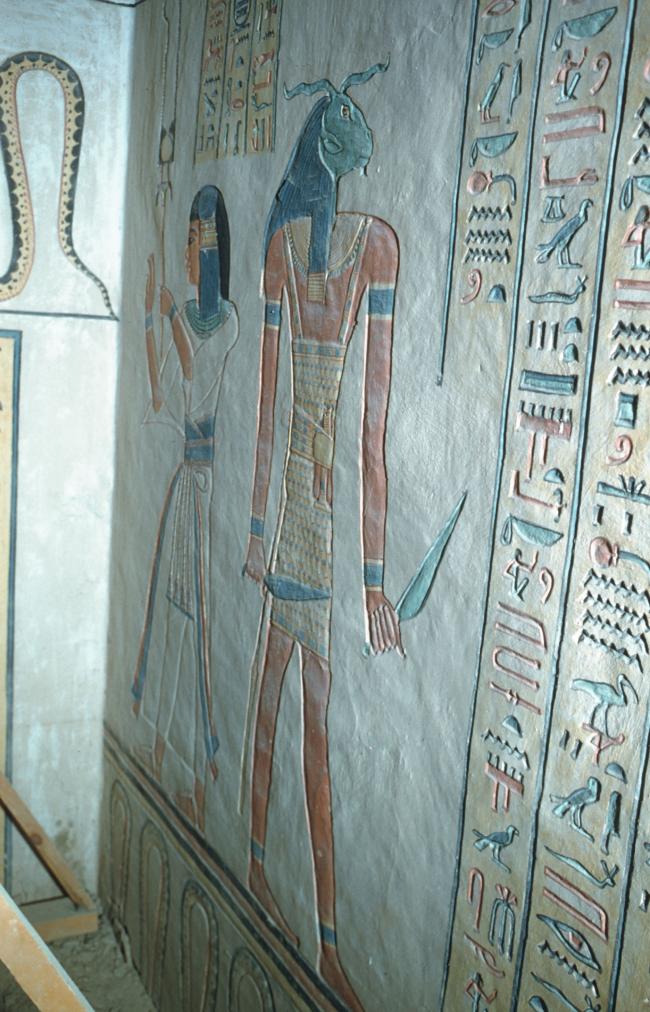

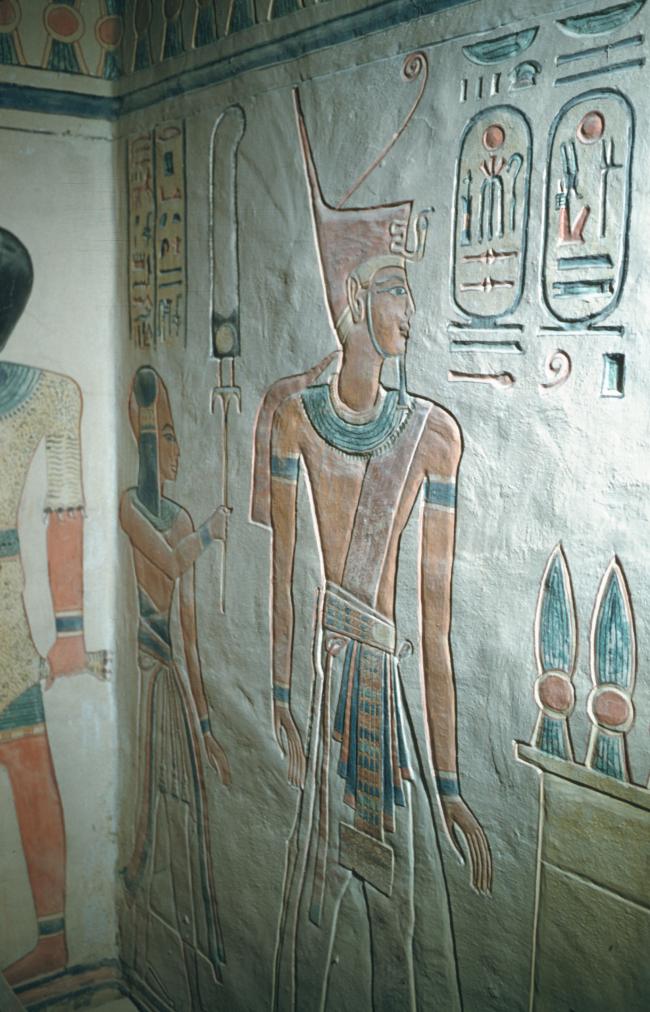

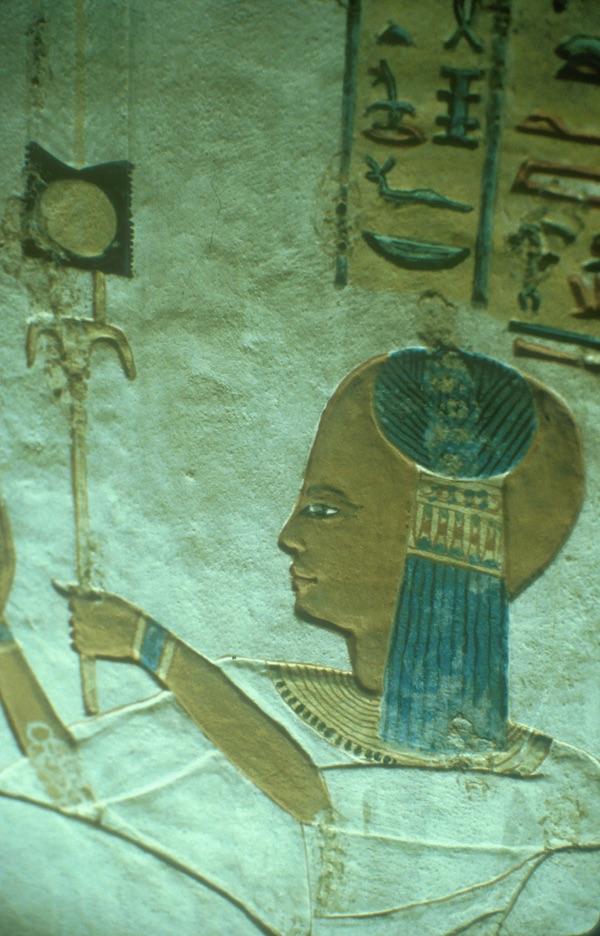

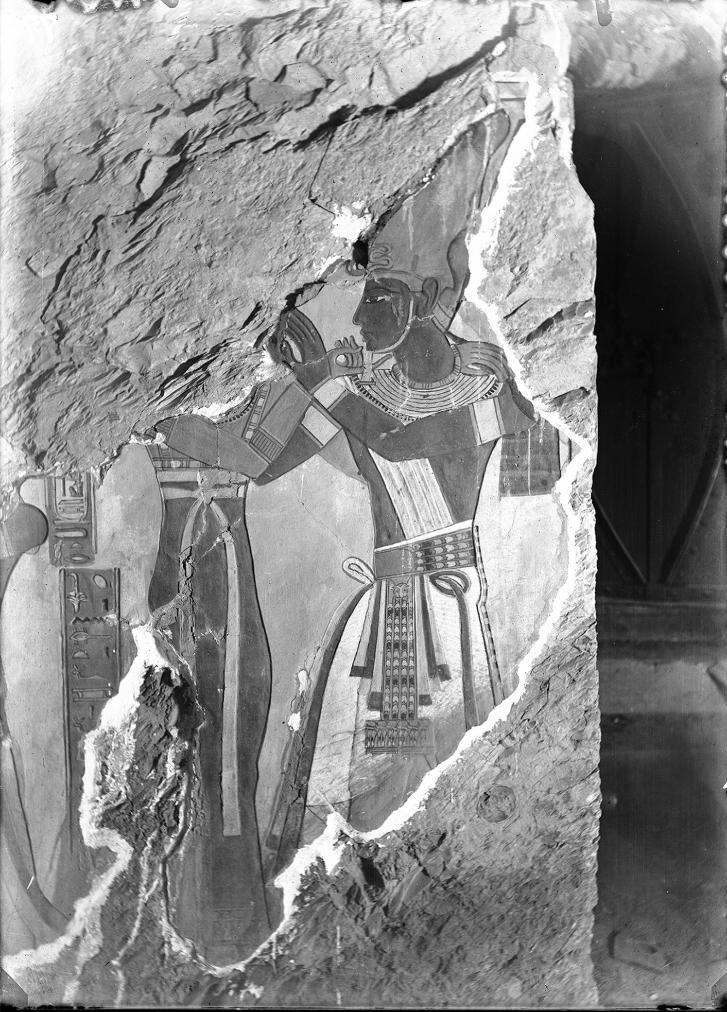

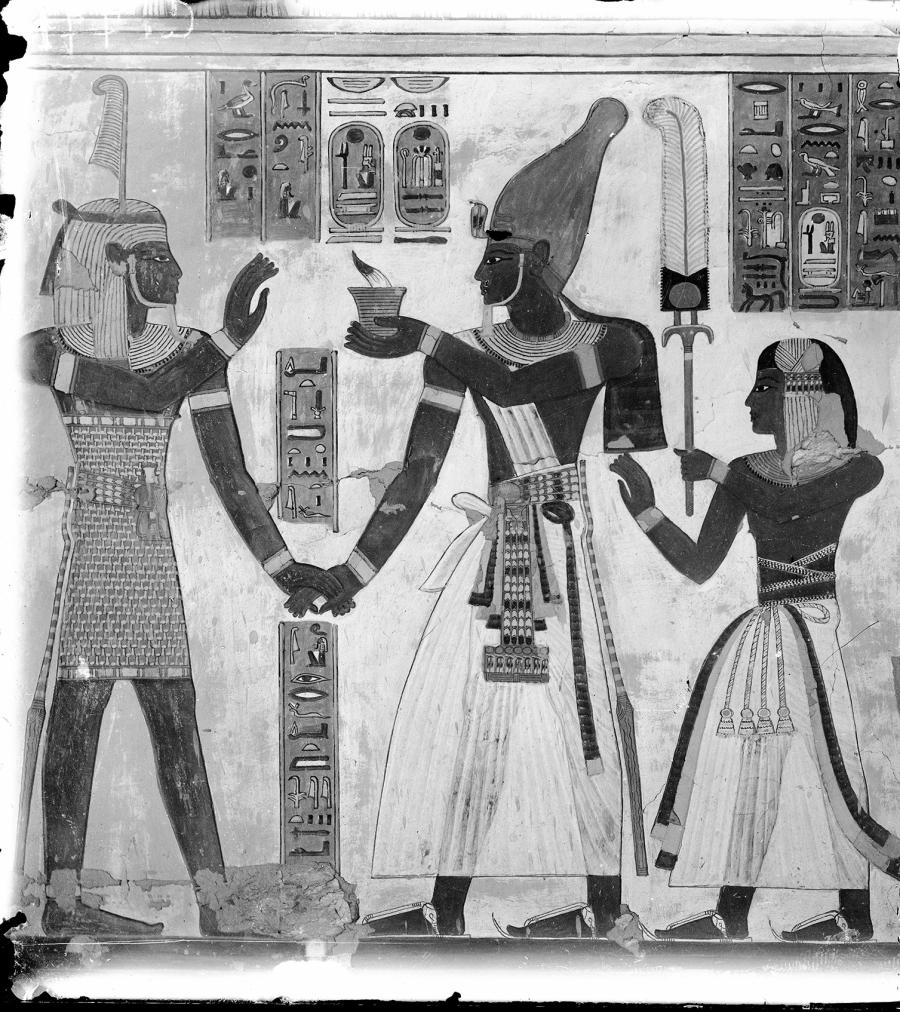

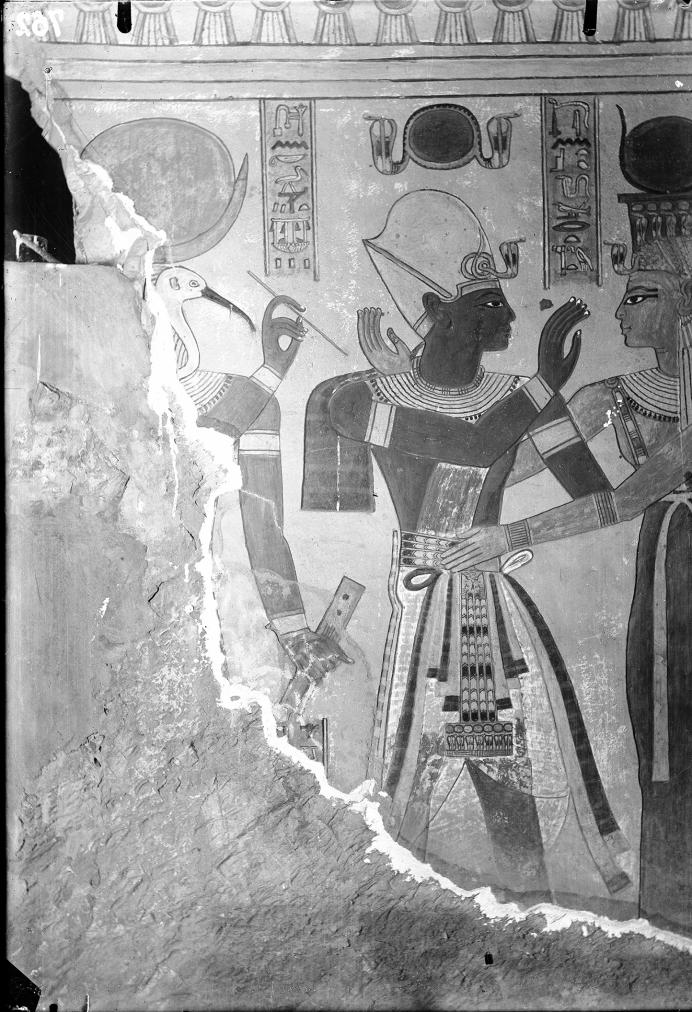

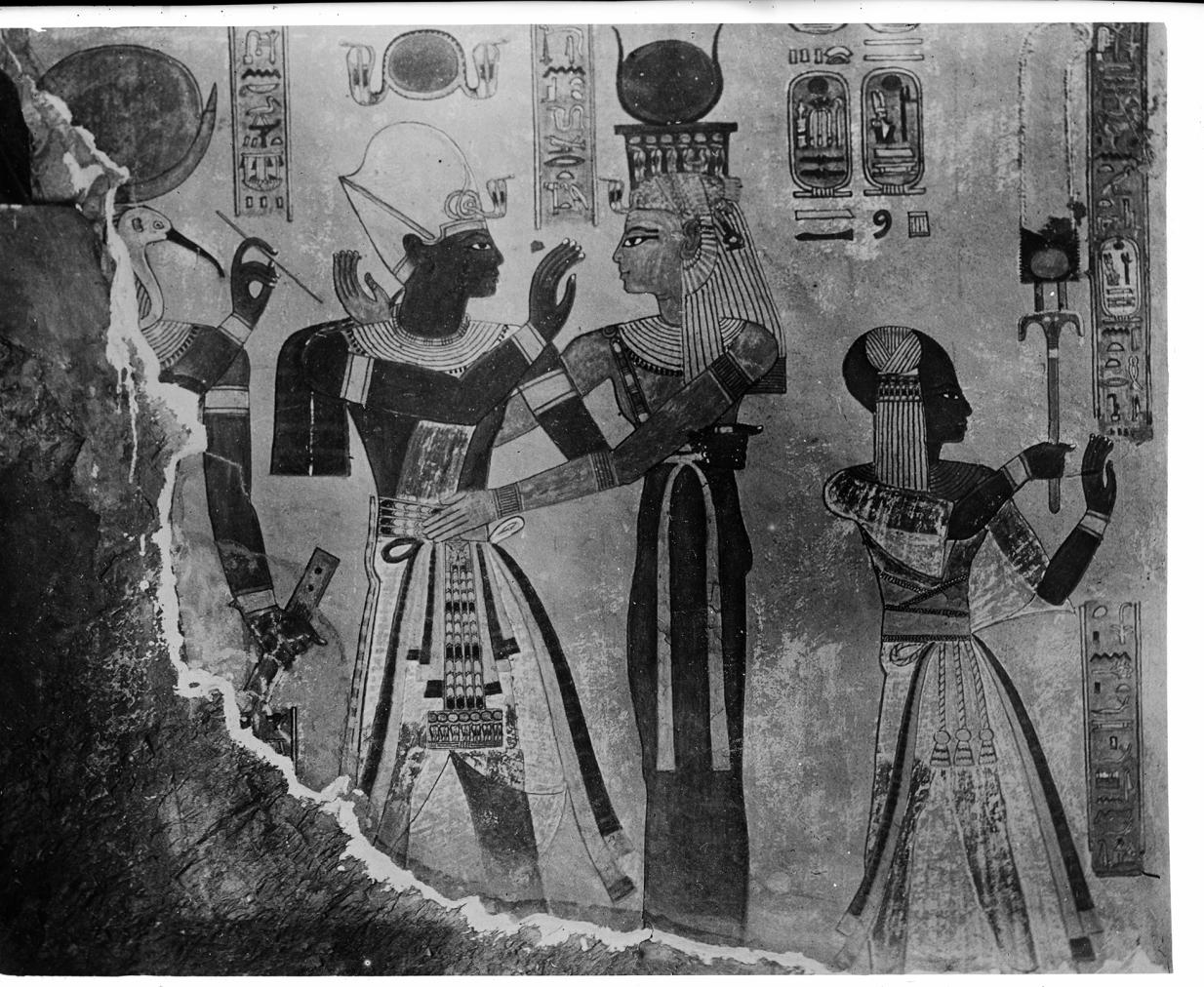

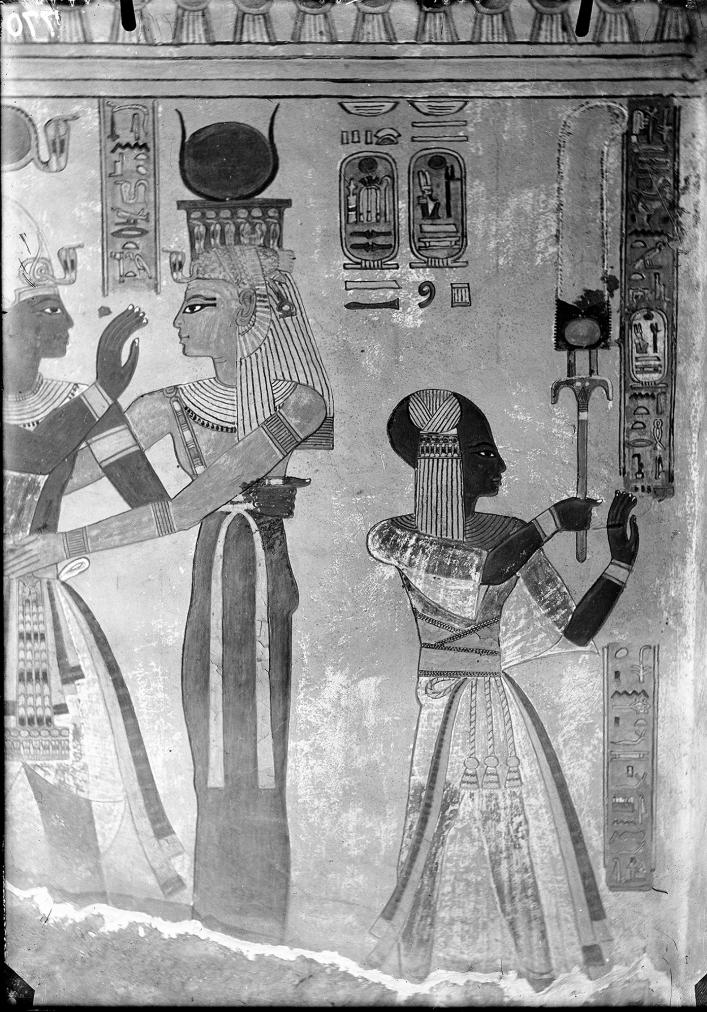

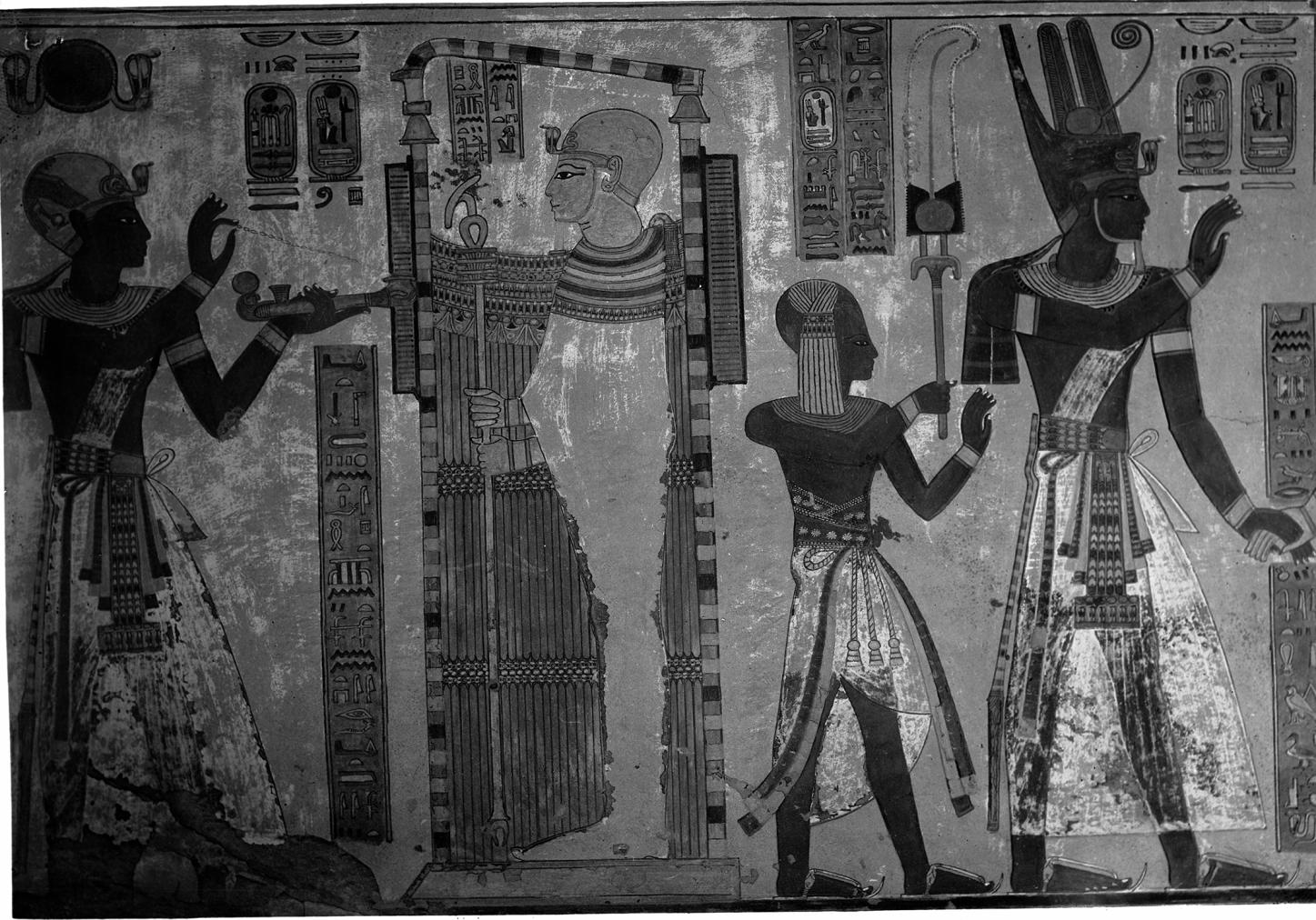

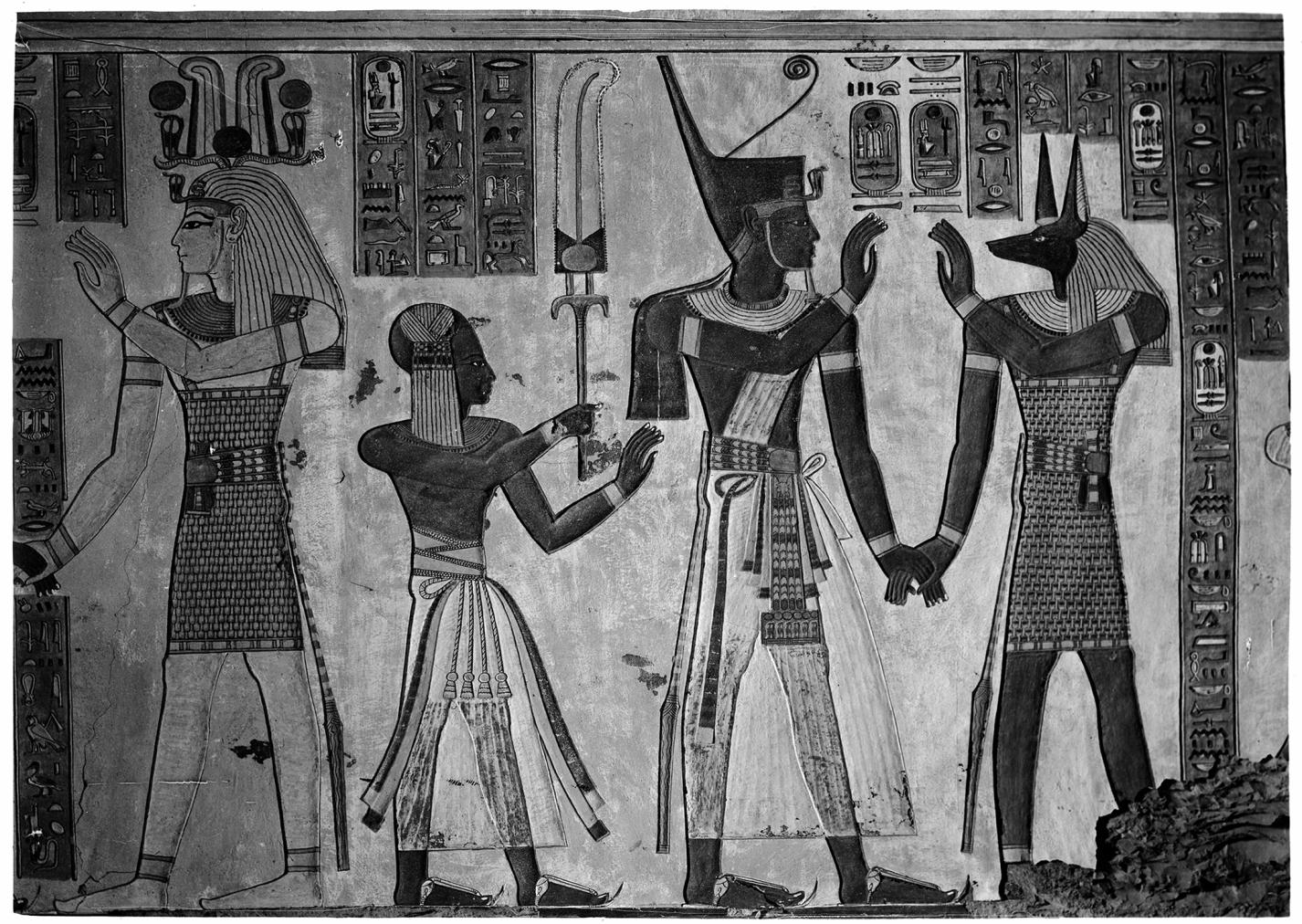

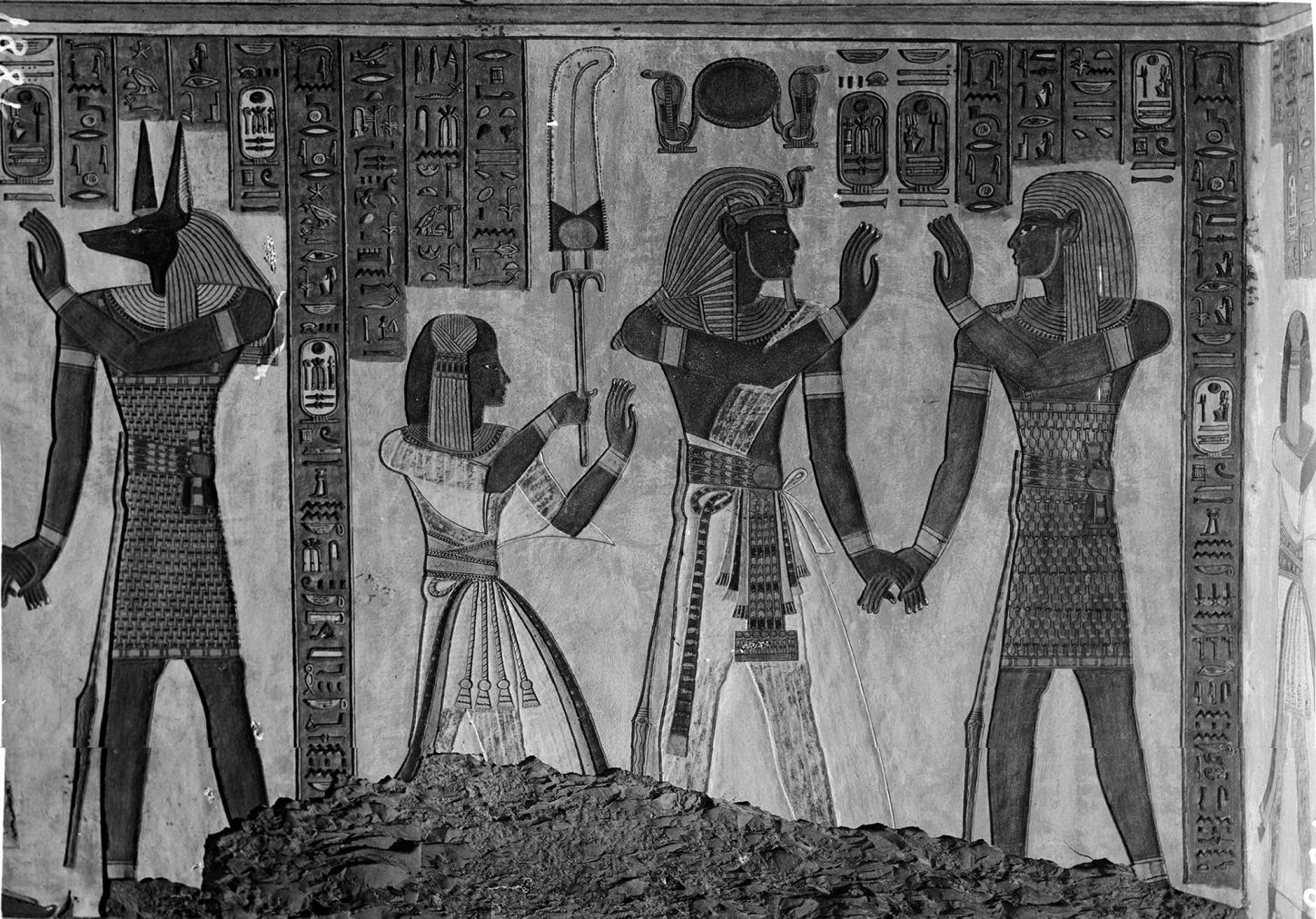

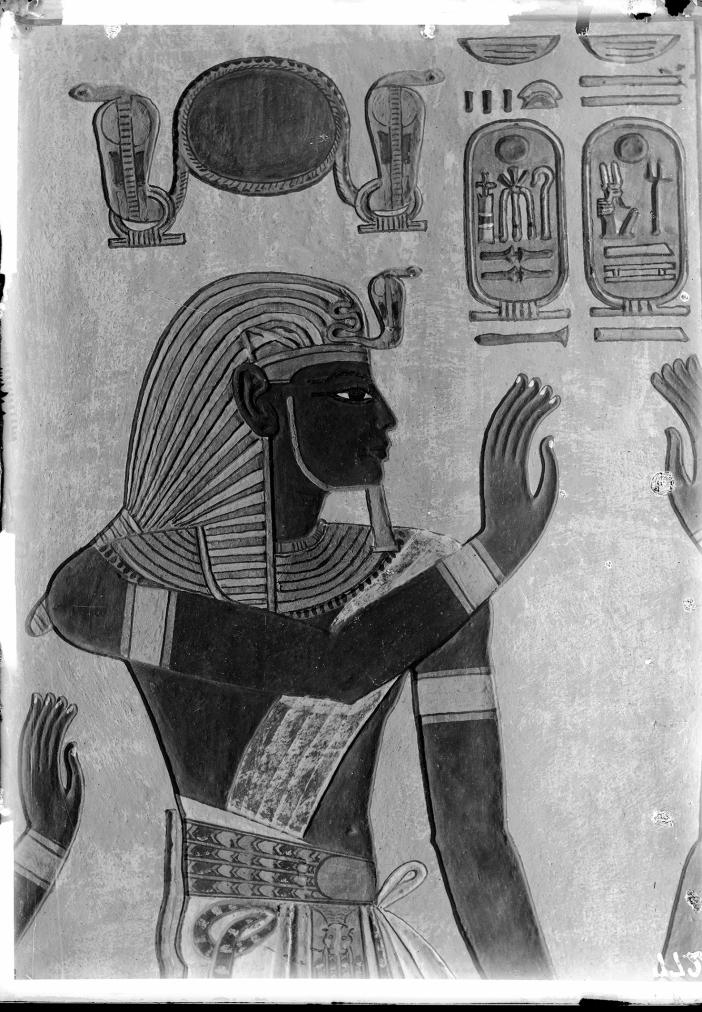

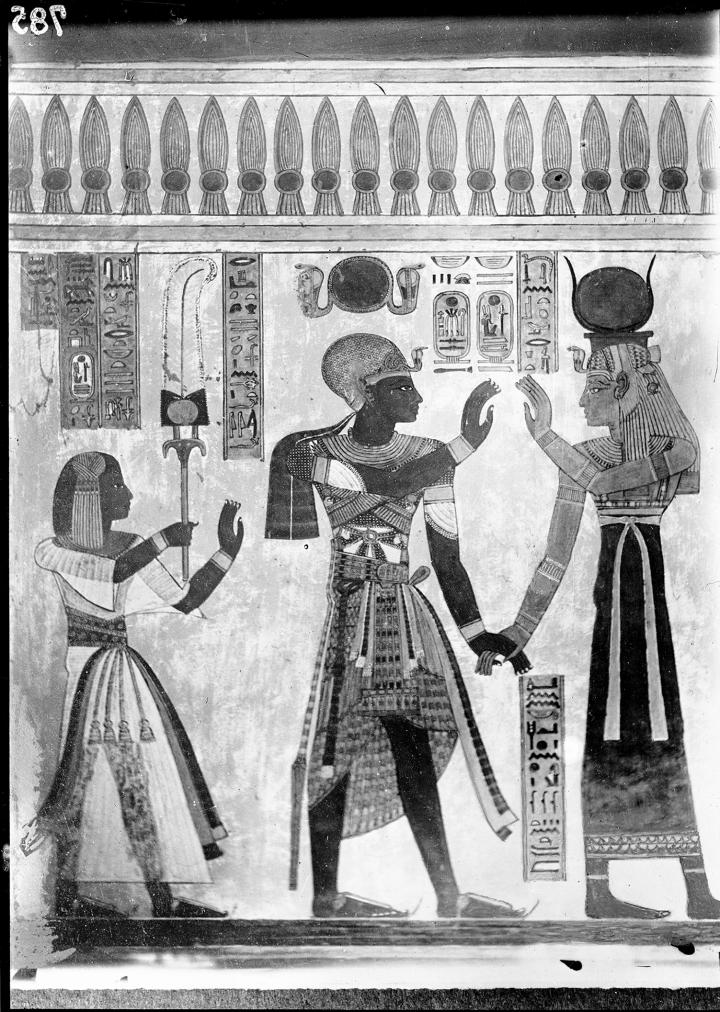

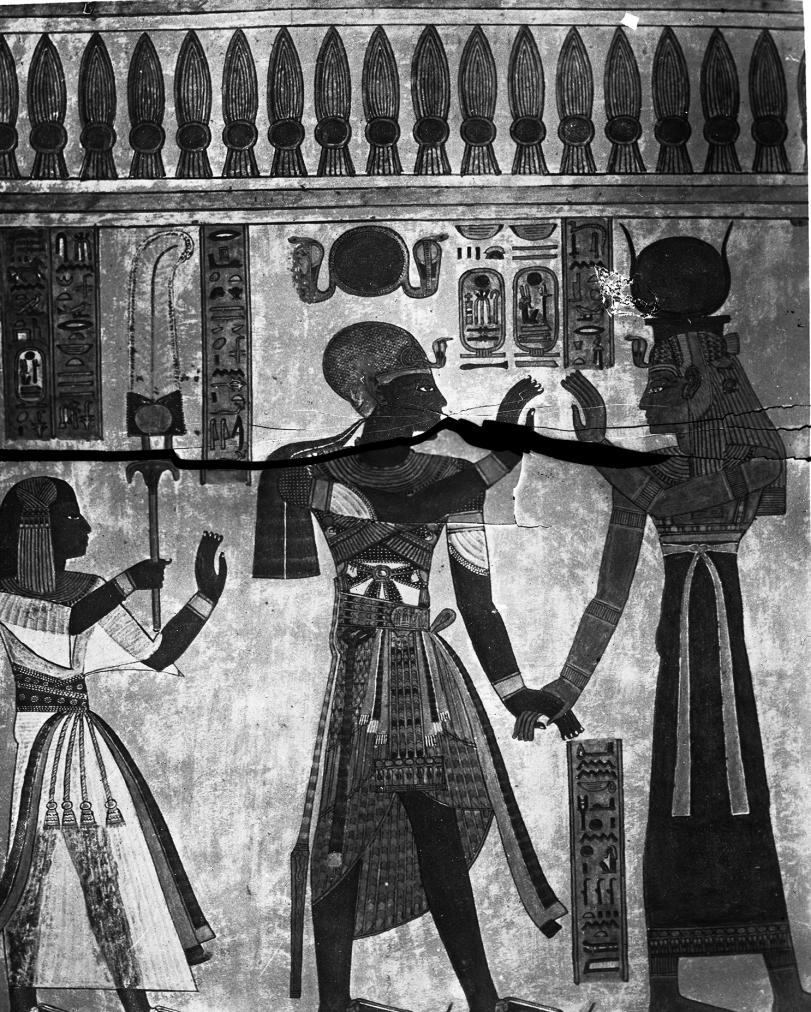

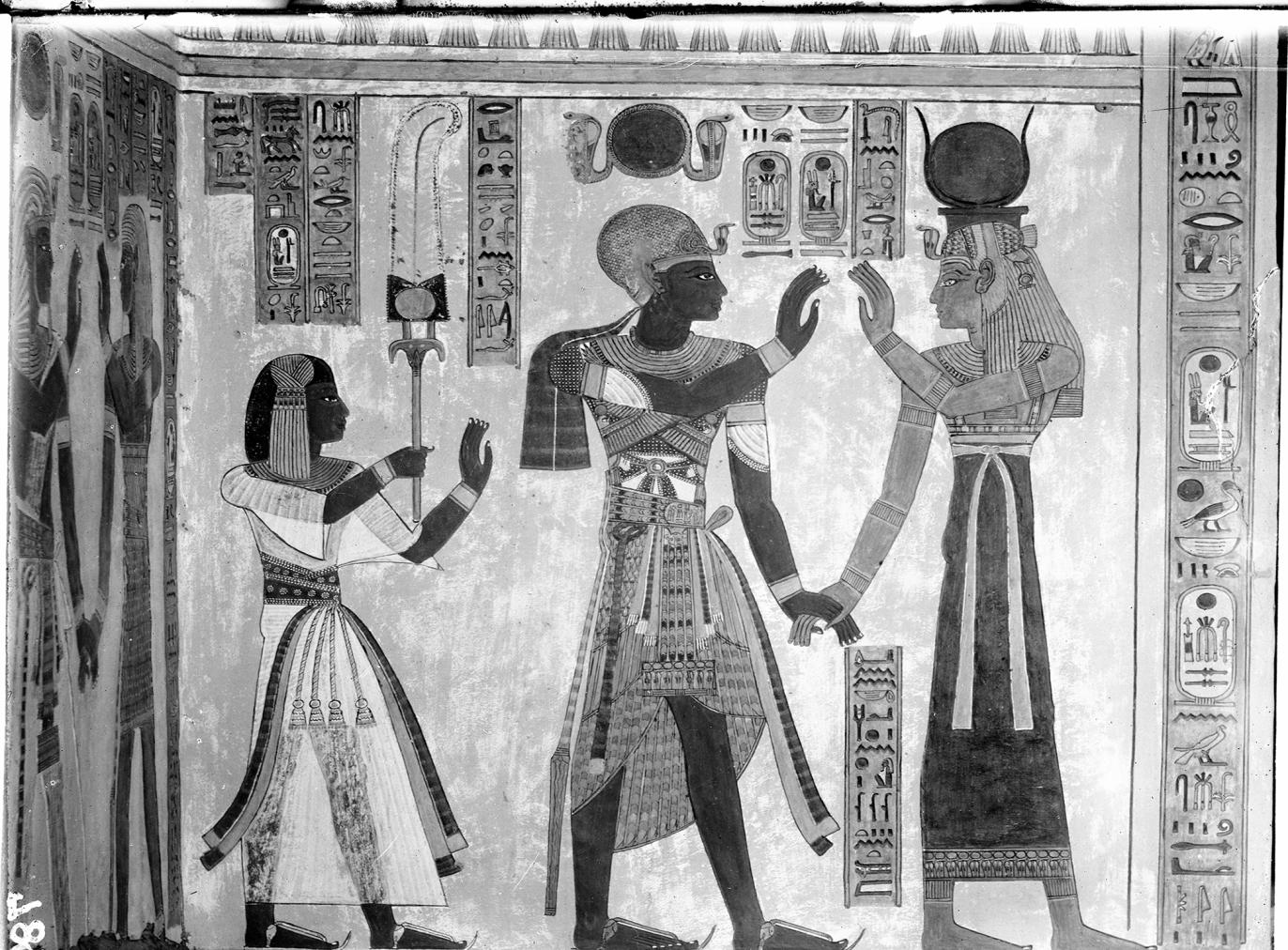

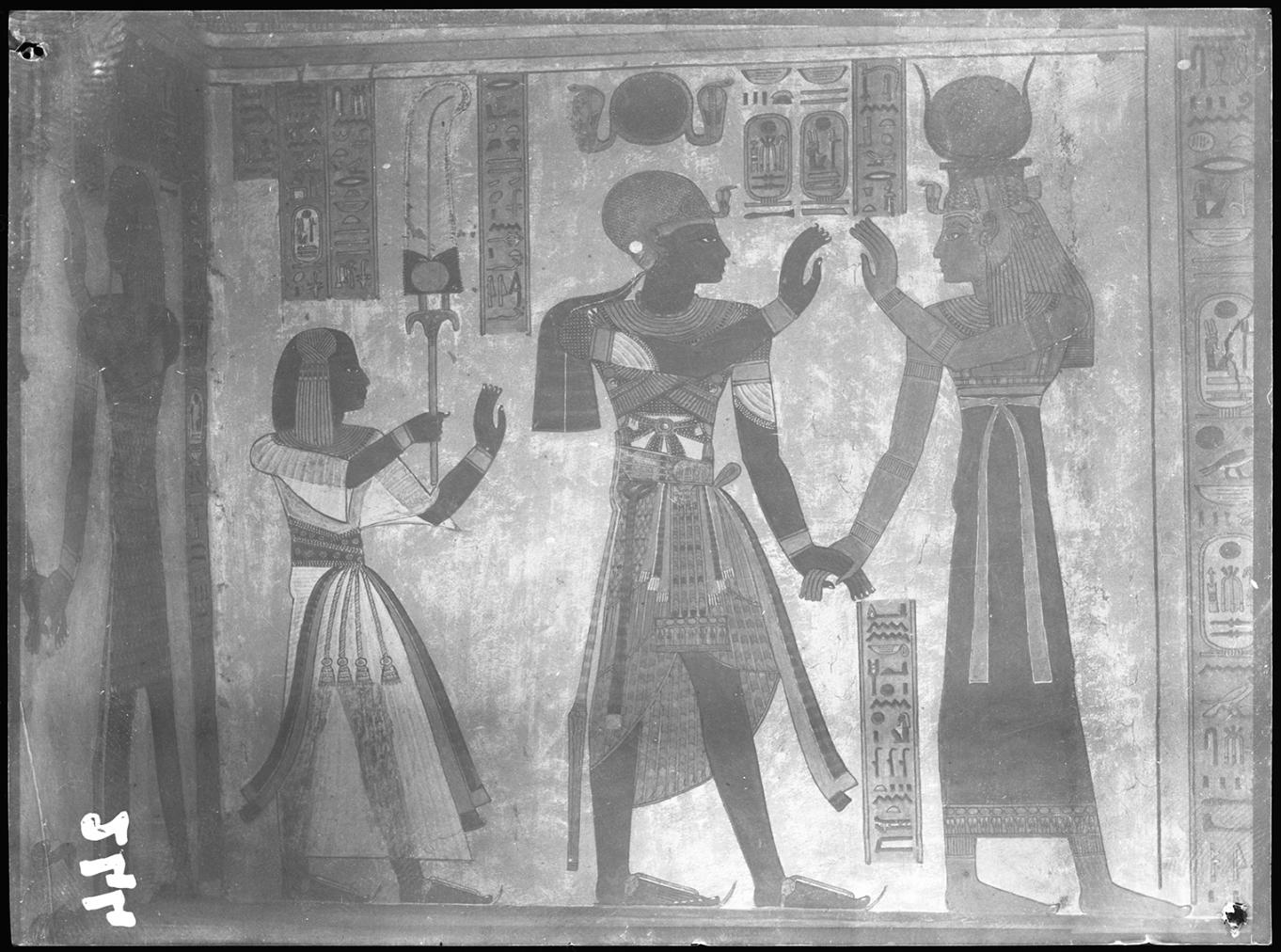

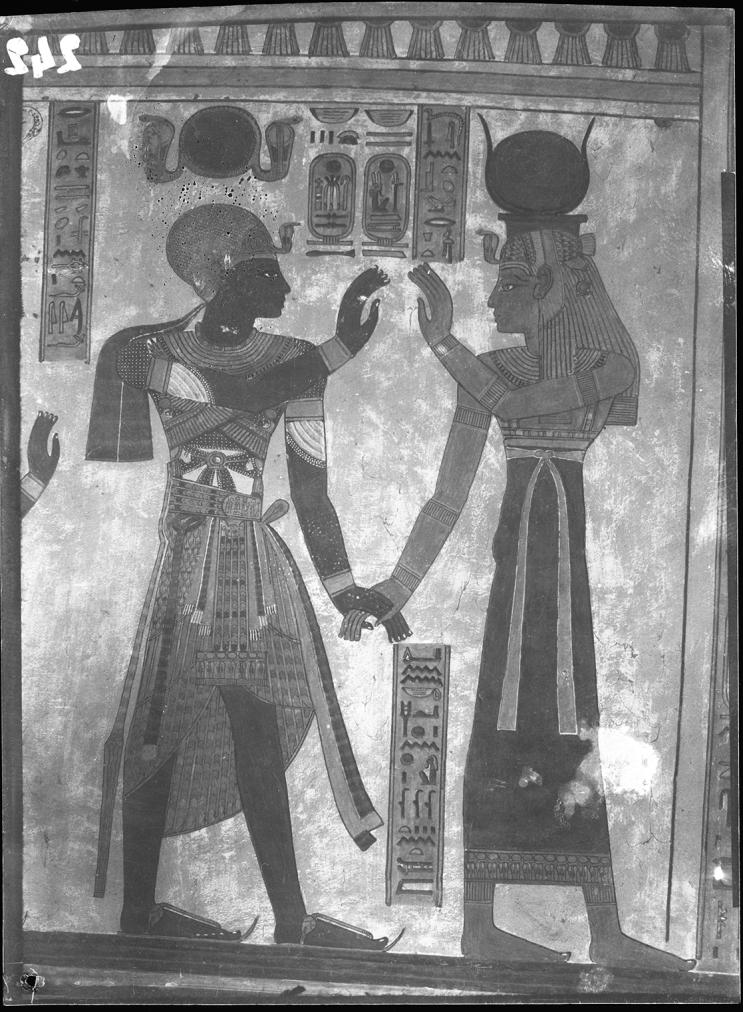

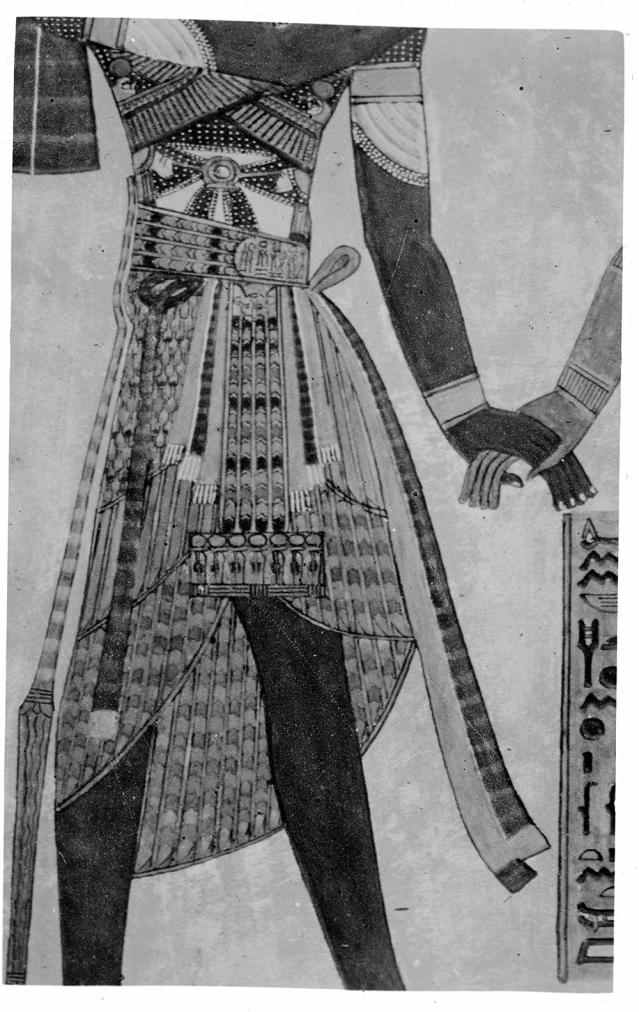

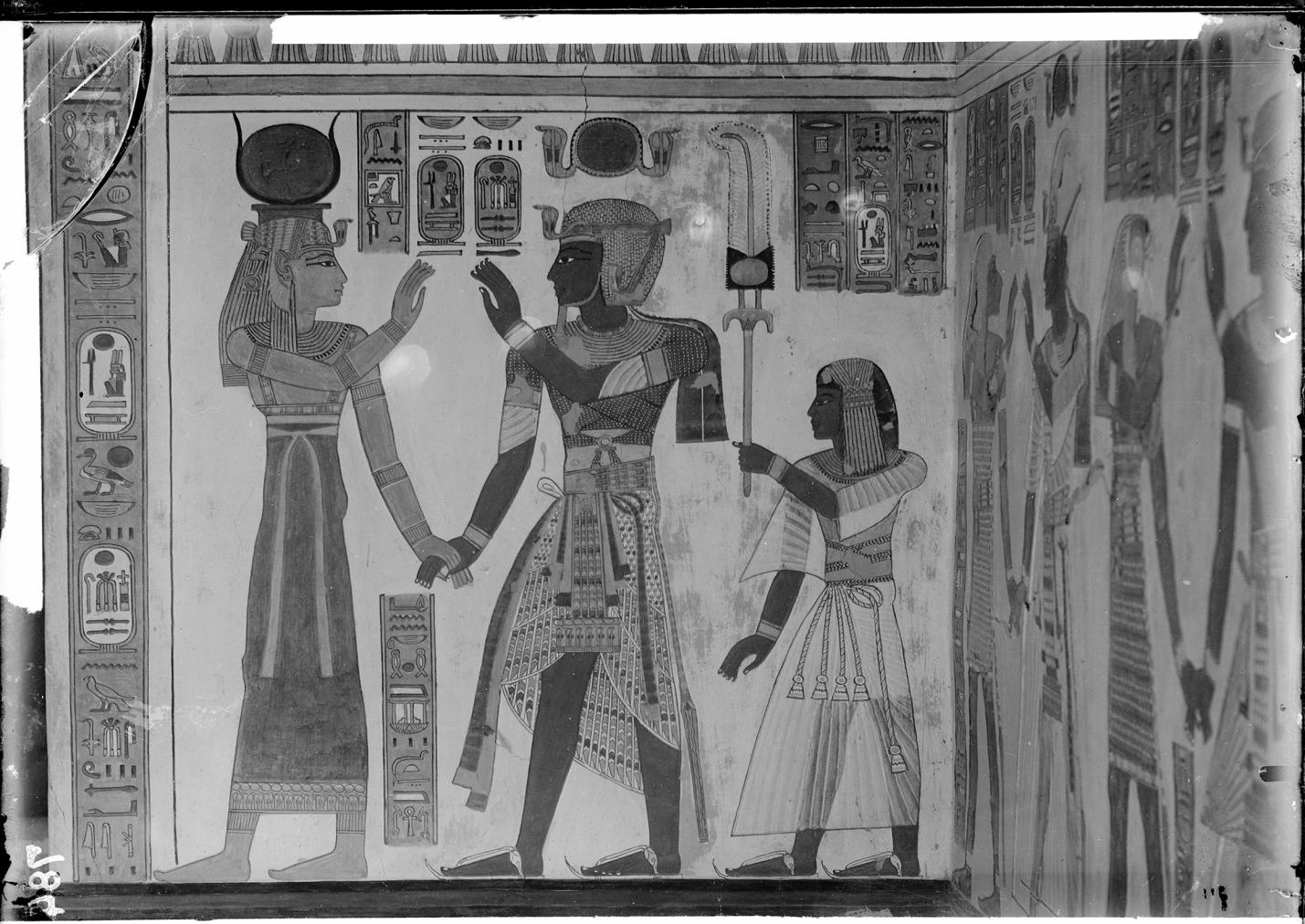

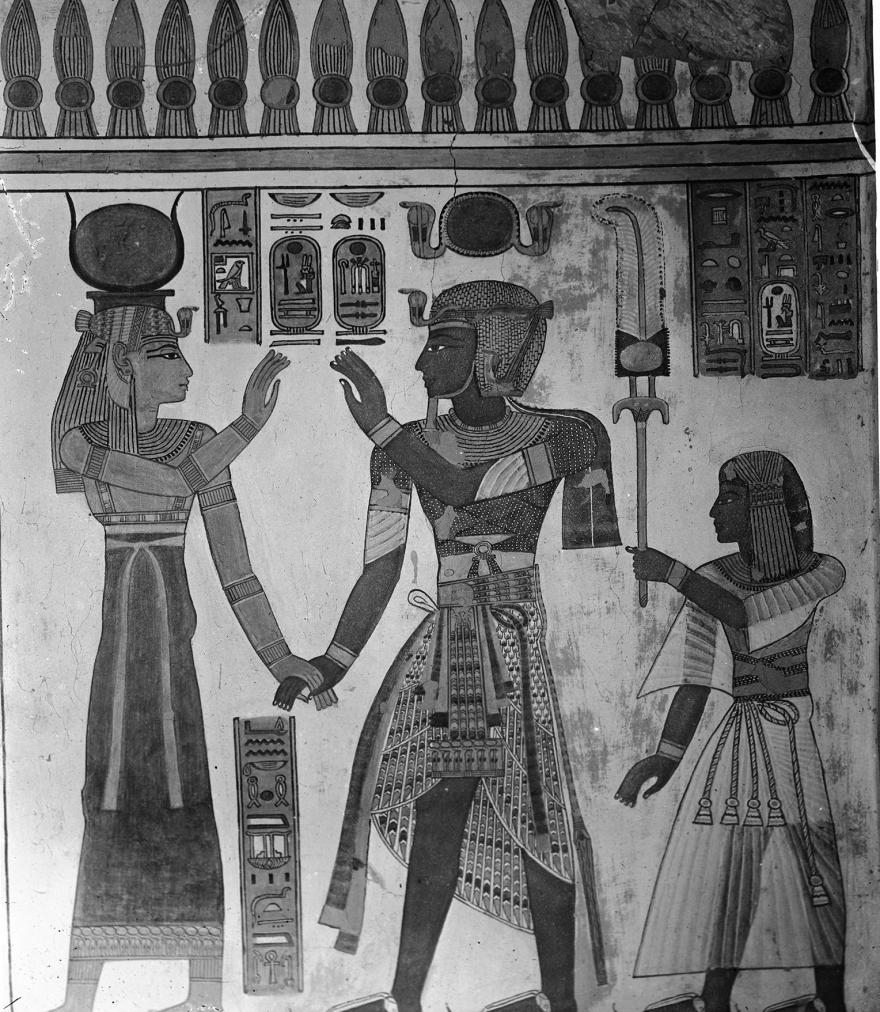

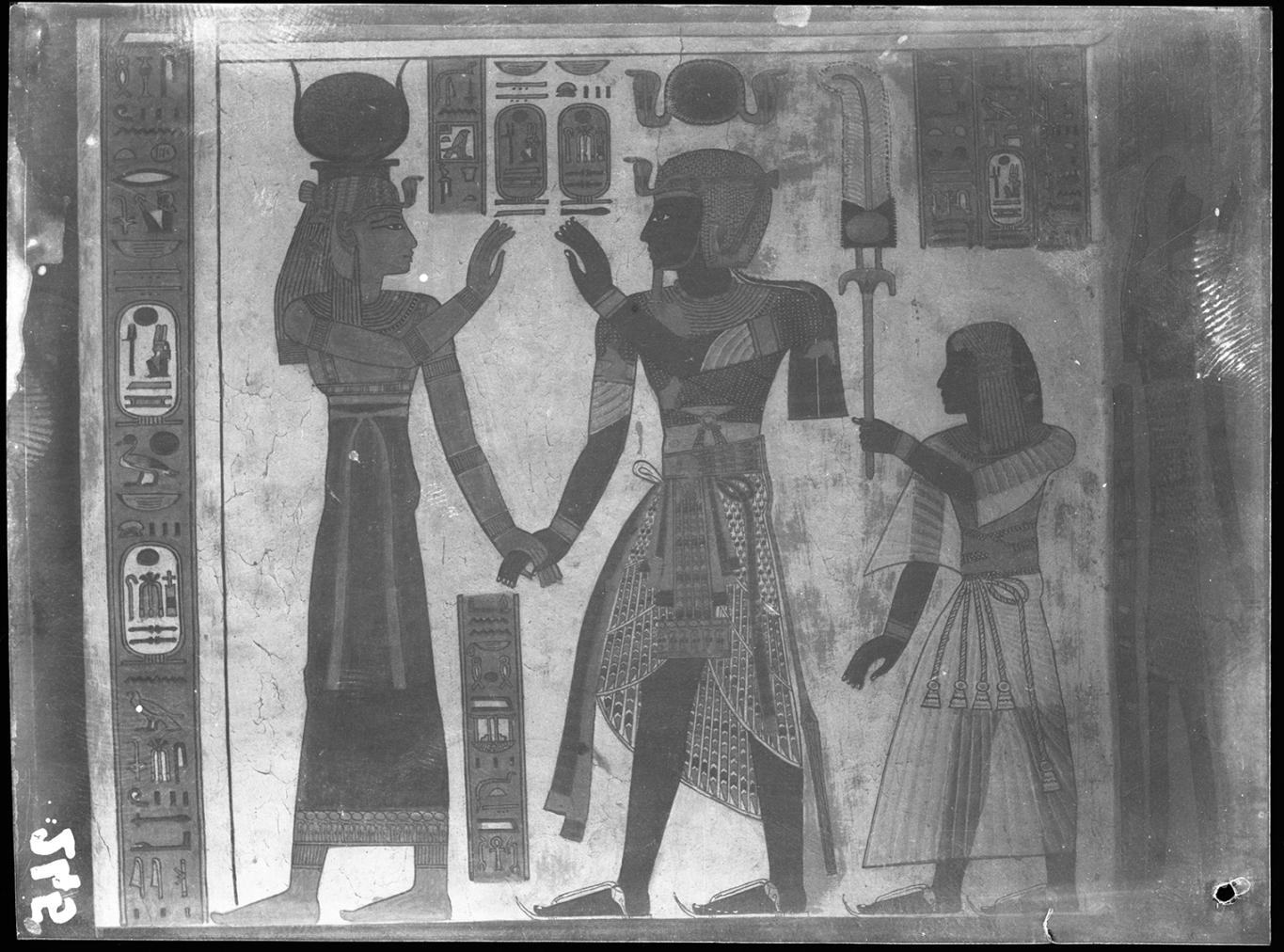

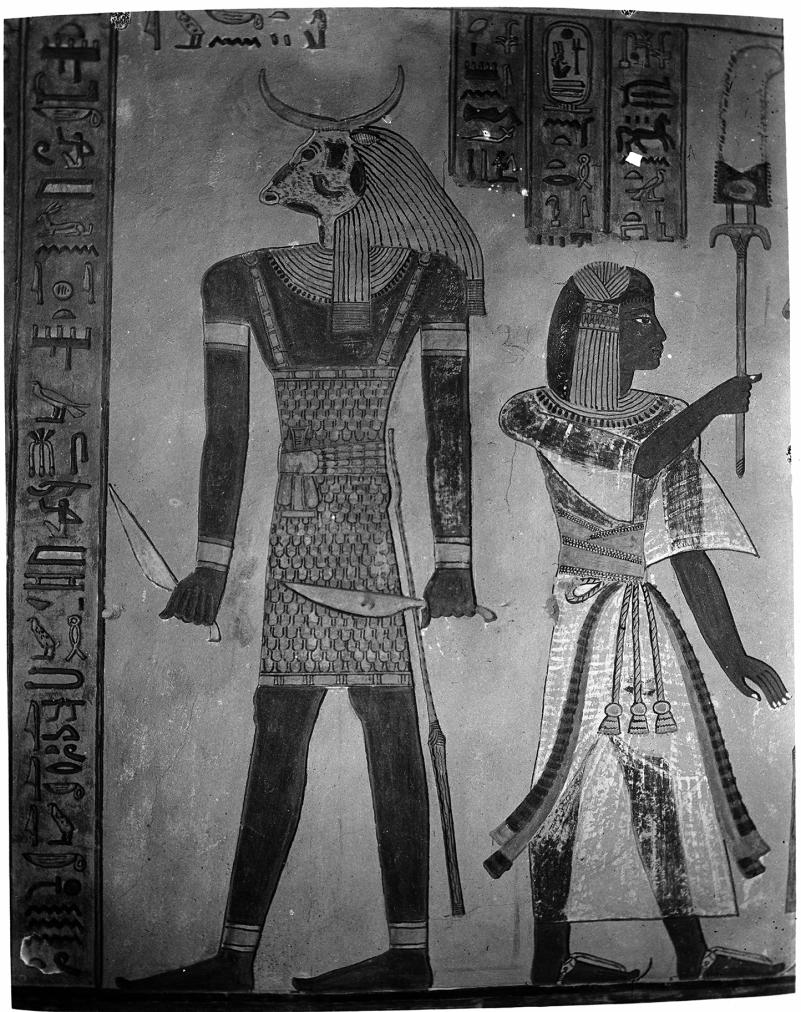

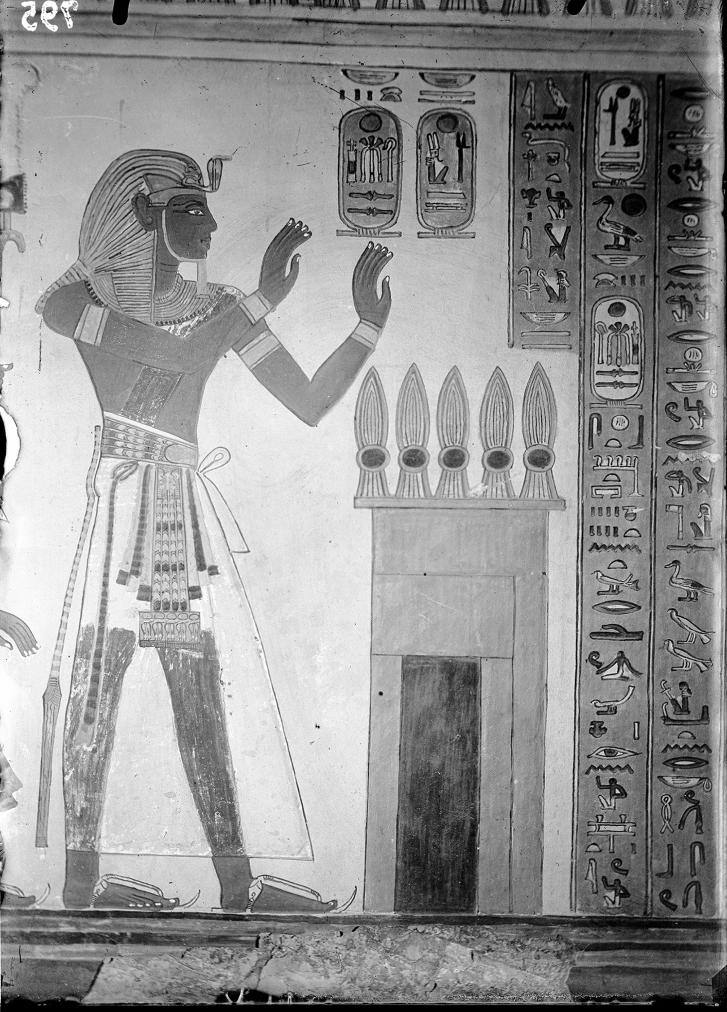

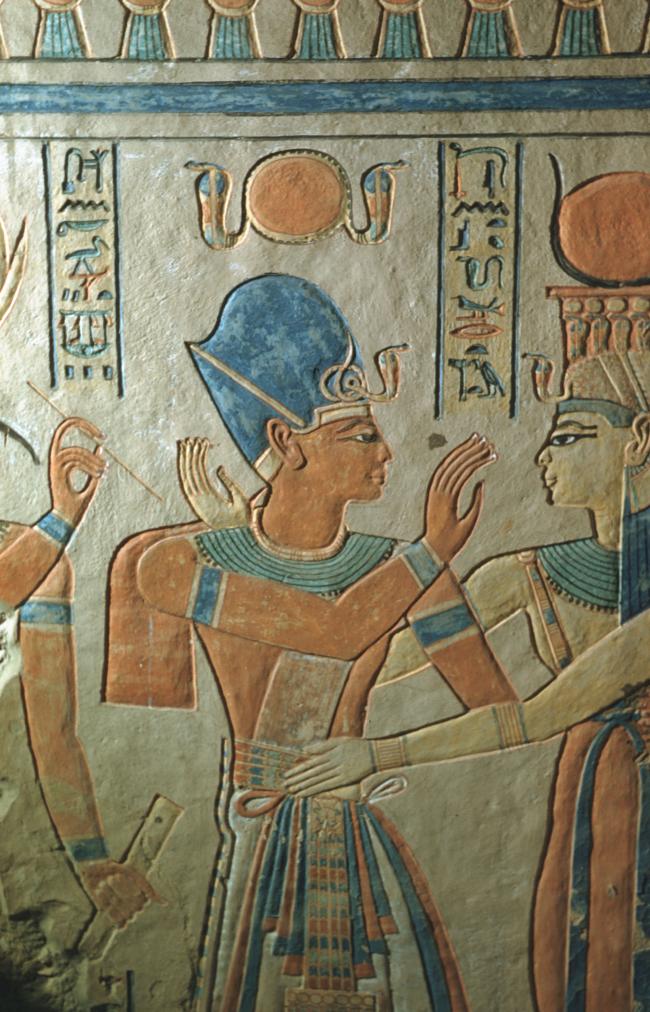

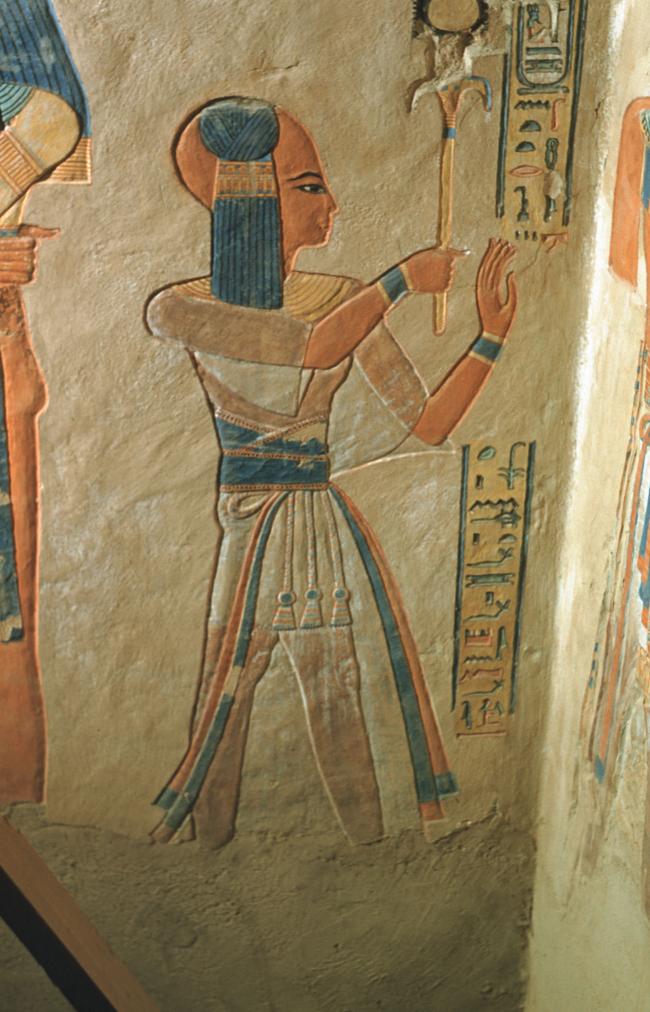

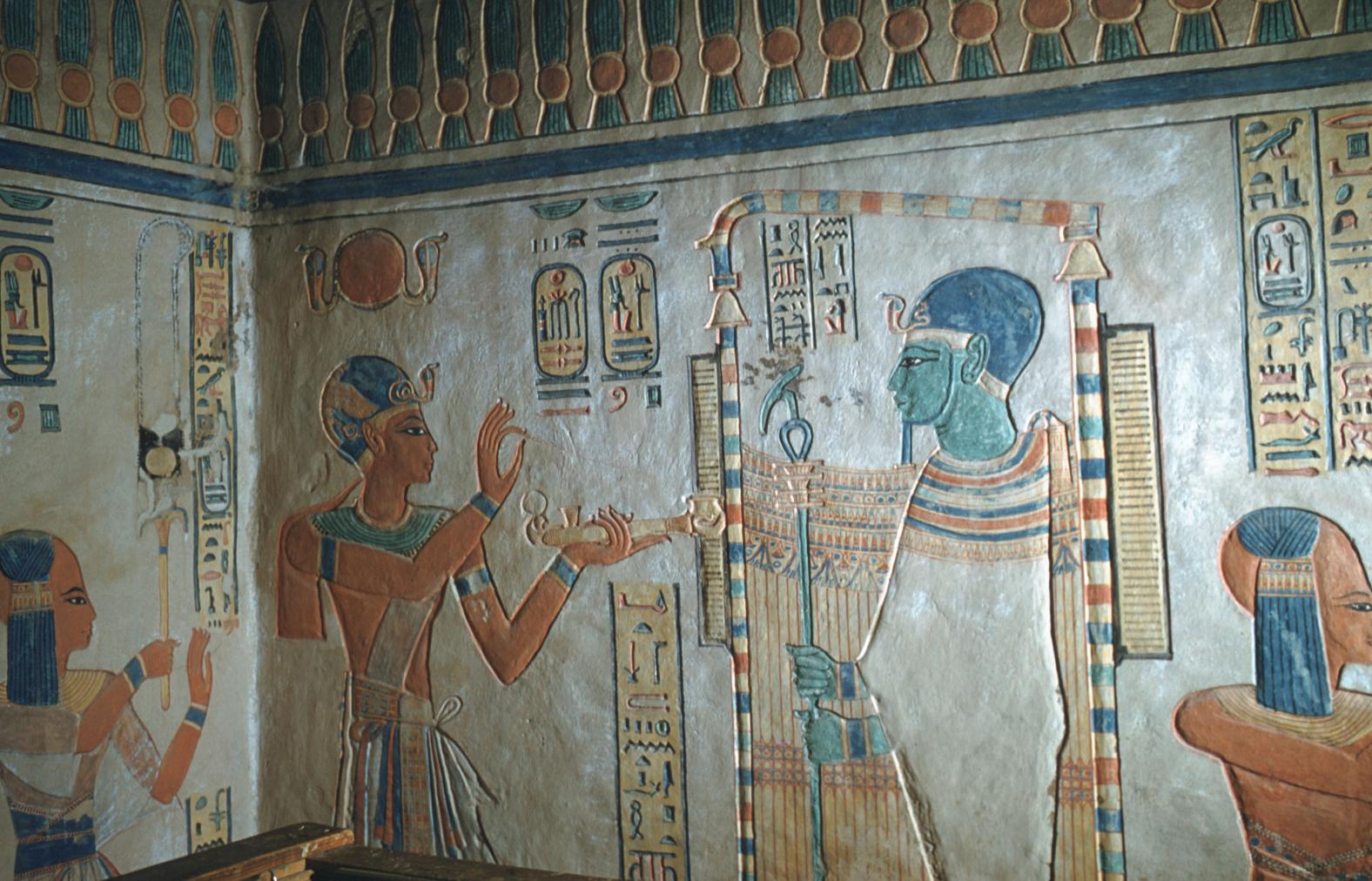

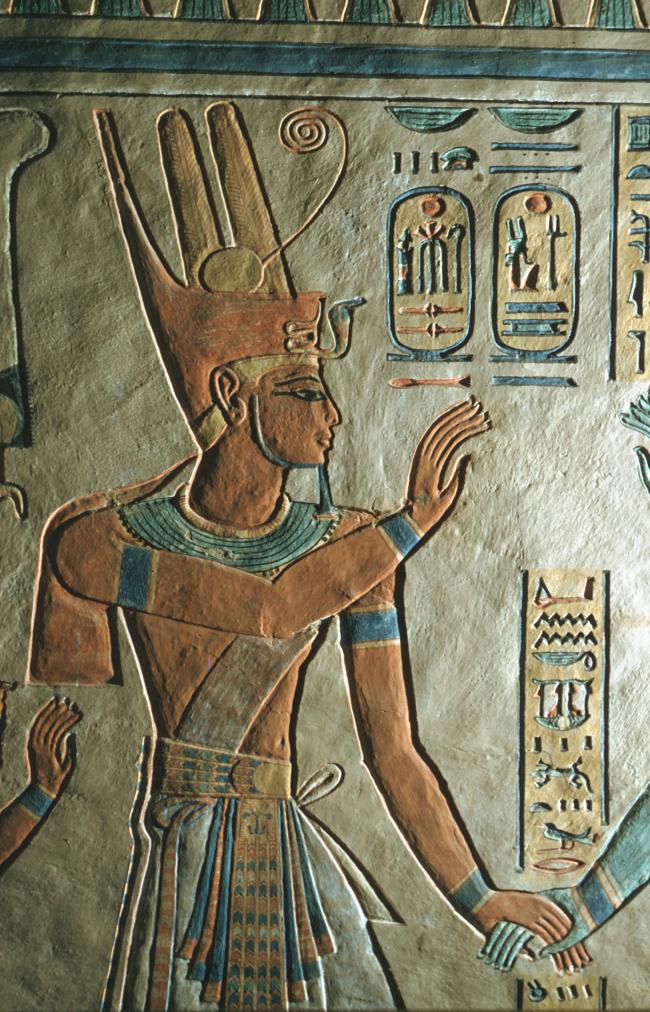

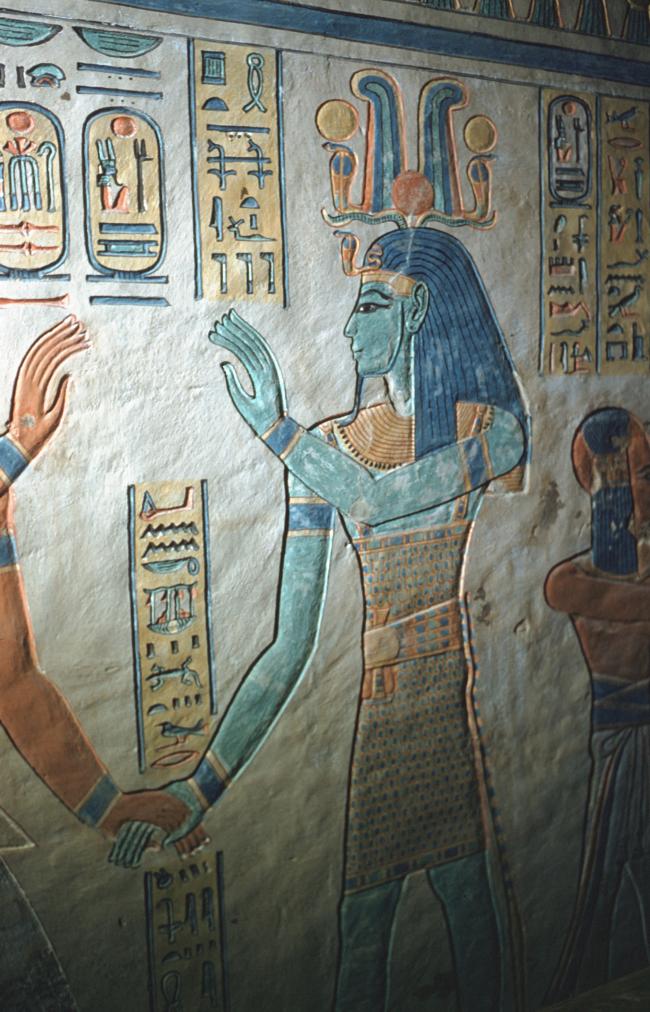

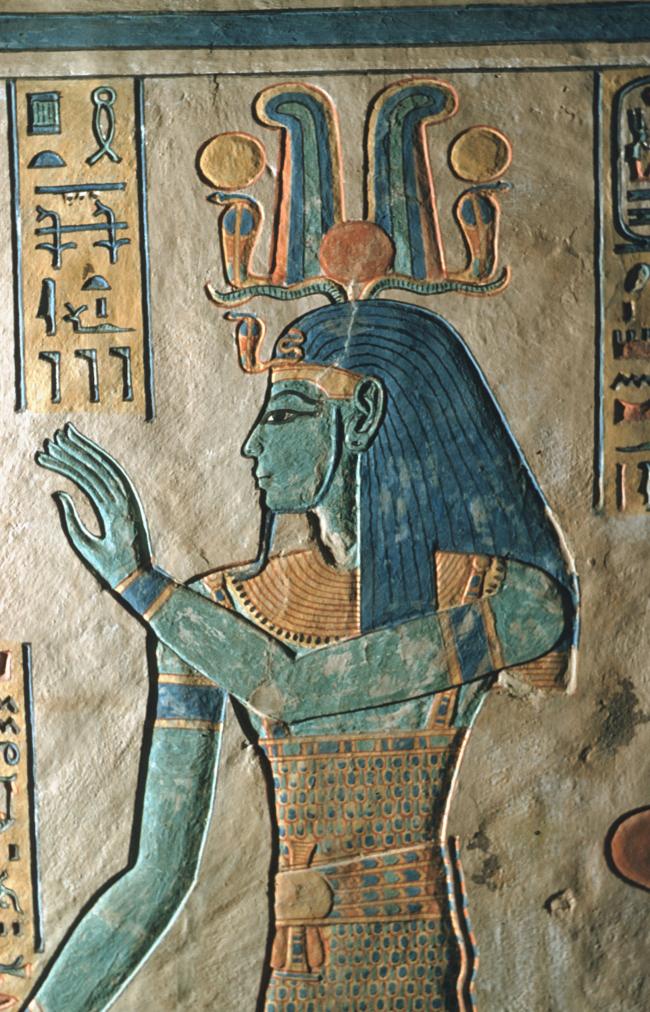

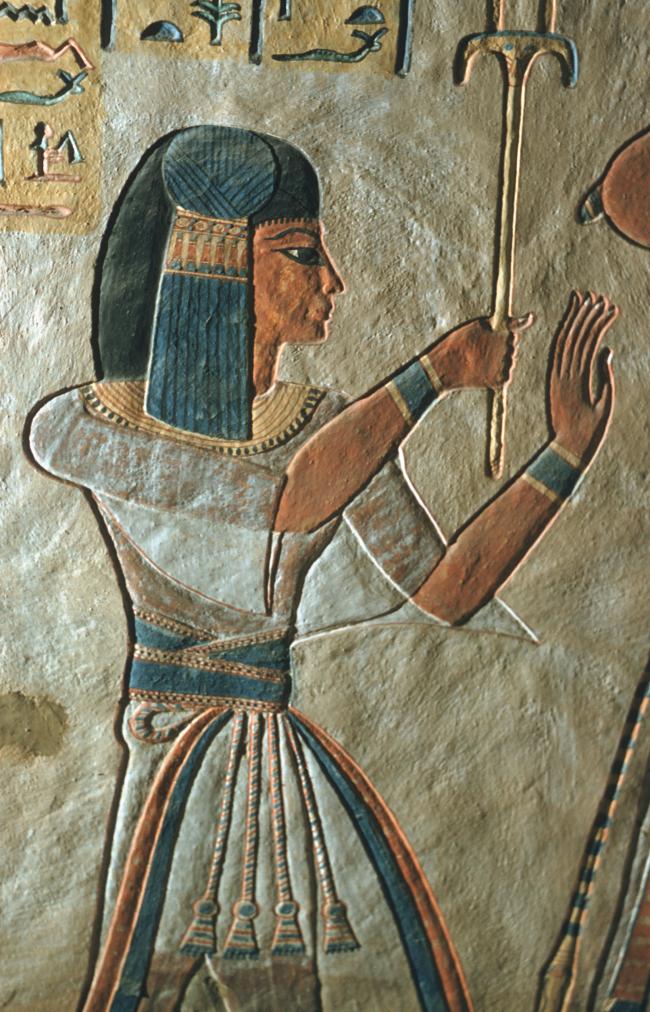

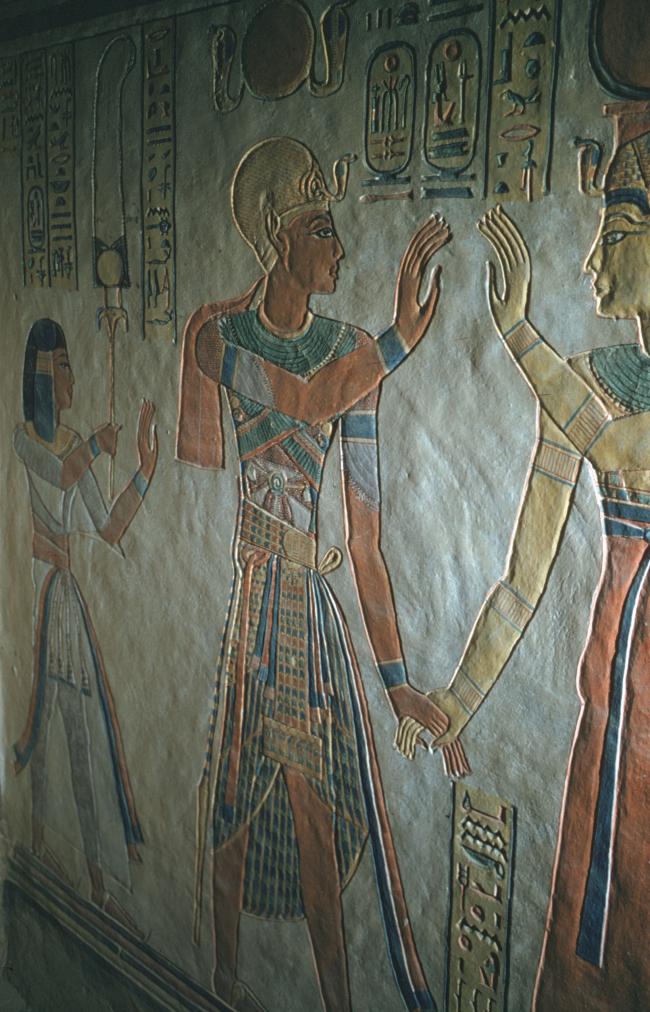

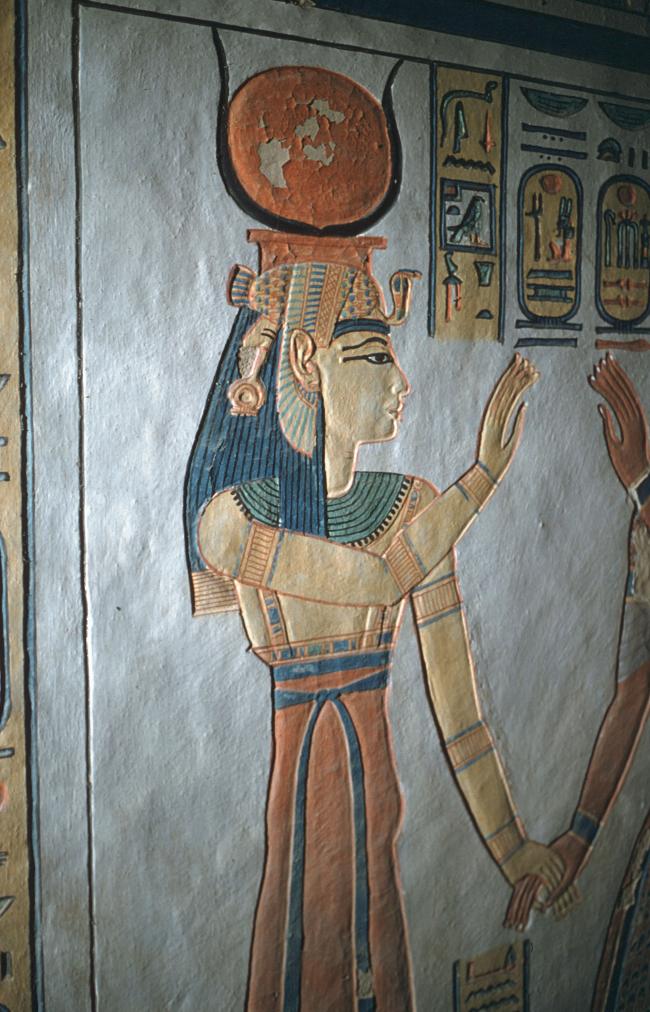

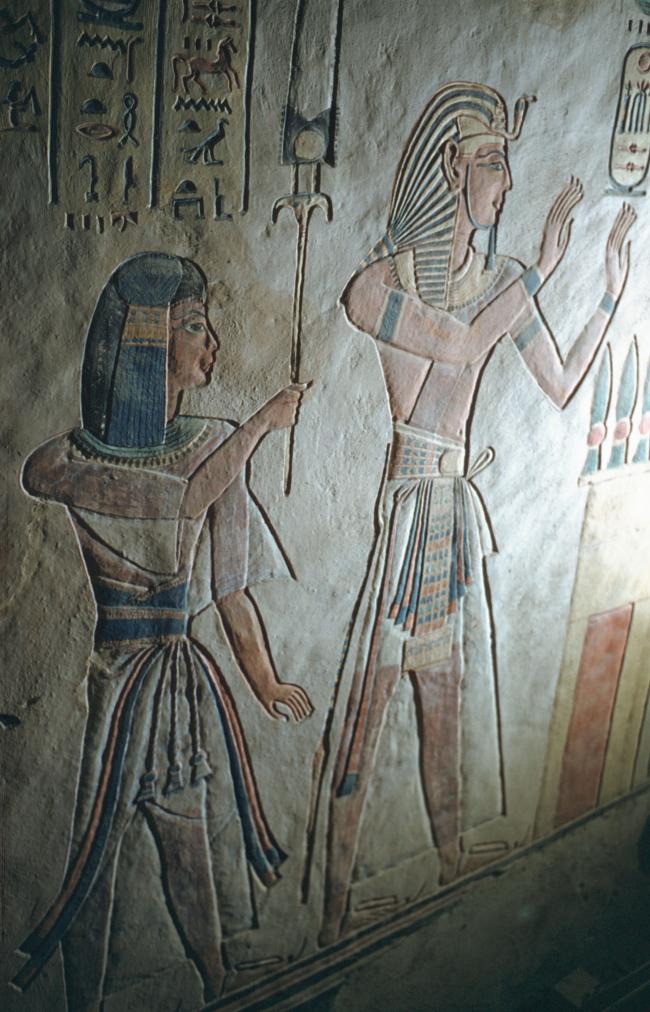

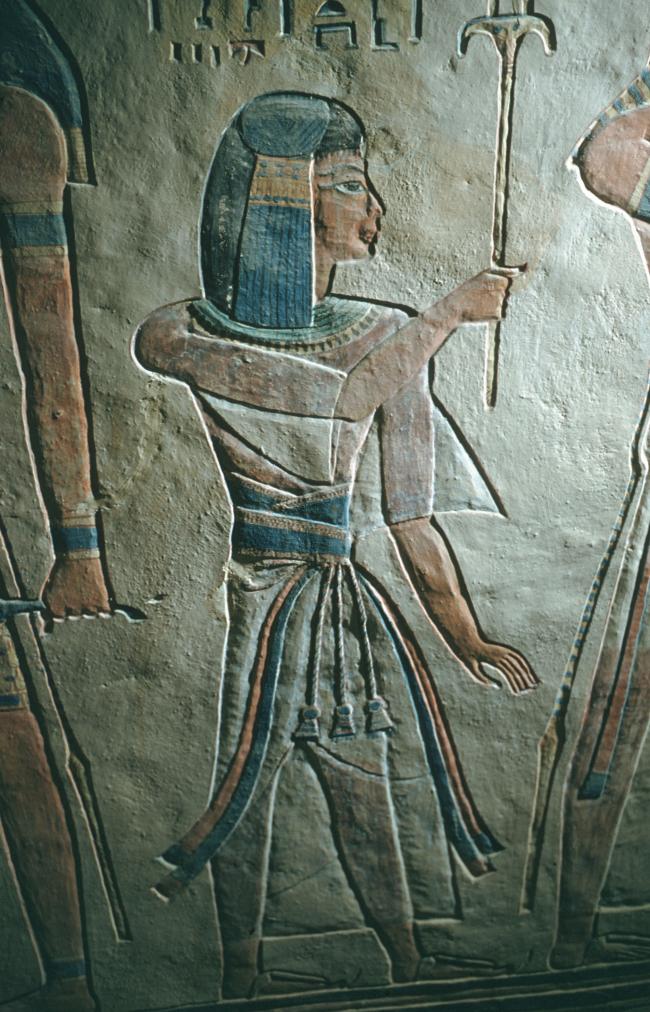

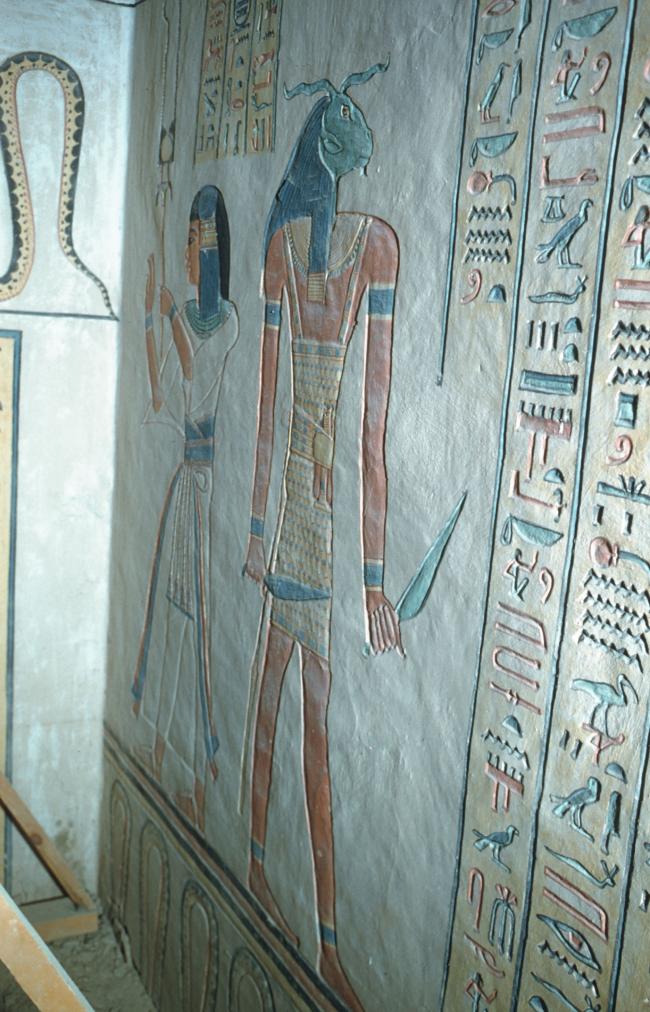

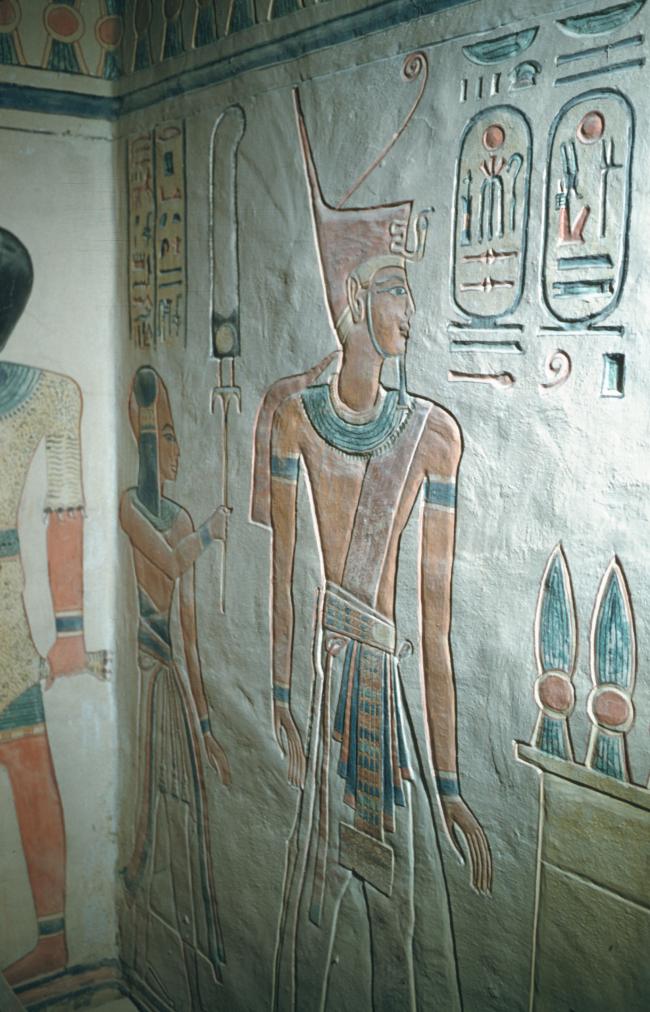

See entire tombThis chamber lies on axis with the tombs entrance. The walls are protected with glass barriers and lit by fluorescent lighting. The chamber is decorated with scenes of the prince and Rameses III offering to various deities. The king is always placed as the dominant figure in the scene, and it is he who actually performs the offerings on behalf of his son. As in QV 42 and QV 44, the prince is shown as a child with the side lock, or Horus lock of youth and carries a long plume.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Ba

See entire tombThis gate lies in the right (northwest) wall of chamber B and leads to a side chamber. The gate is undecorated. A mummified fetus, found in the tomb of Prince Ahmose (QV 88) by the Italian Archaeological Expedition in 1903, is now on display in this gate behind the glass barrier.

Side chamber Ba

See entire tombThis side chamber was left unfinished, with only the plaster and a few line drawings of figures on the walls.

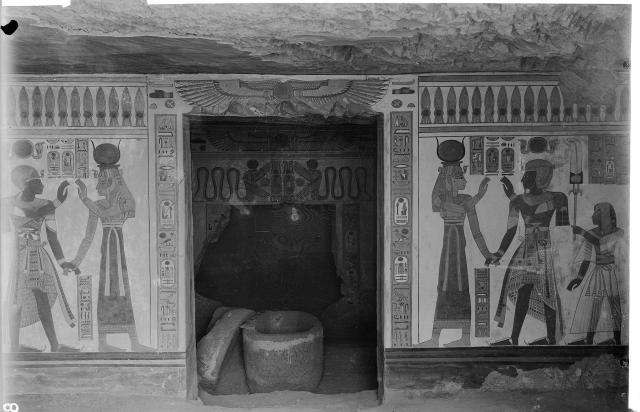

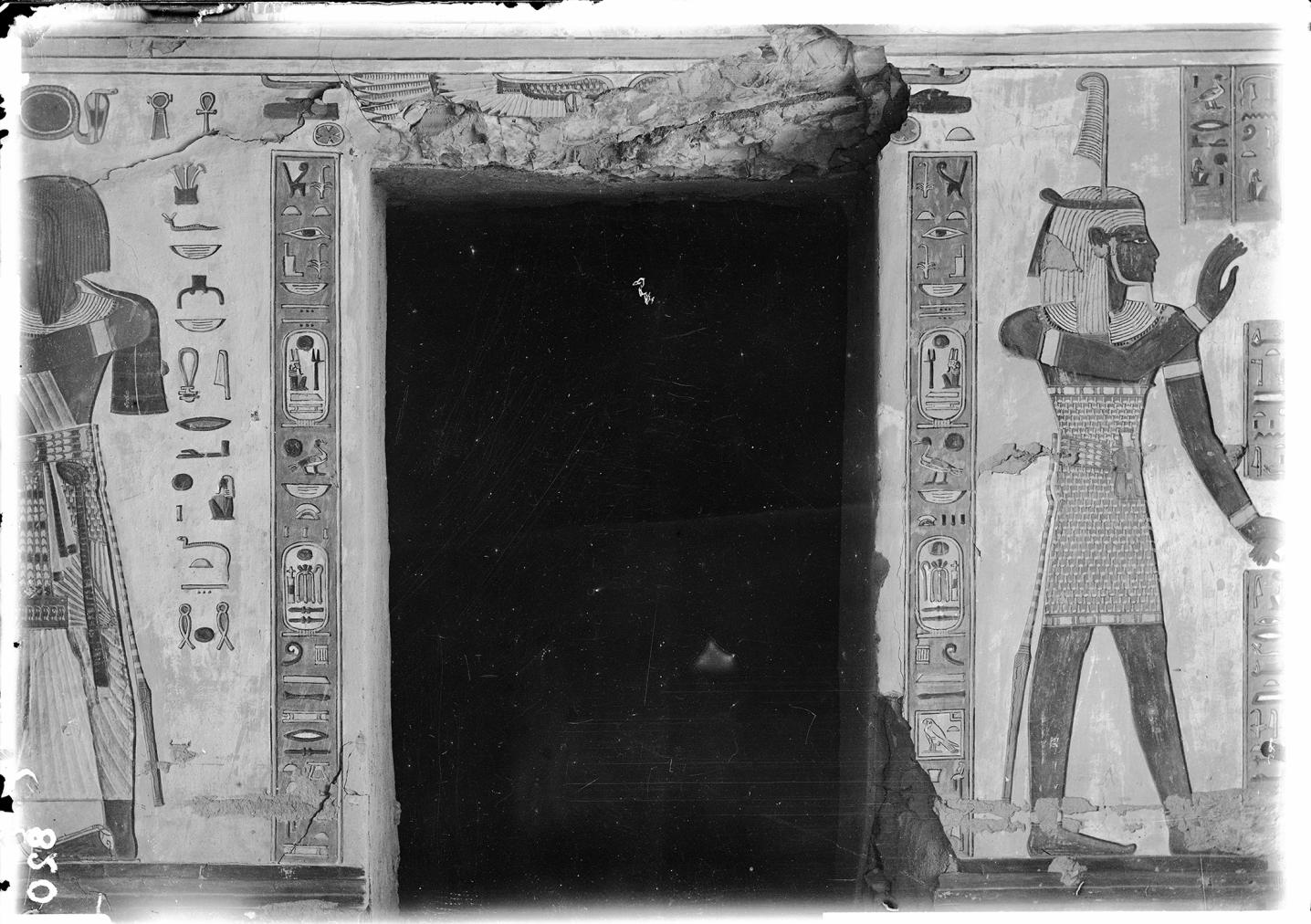

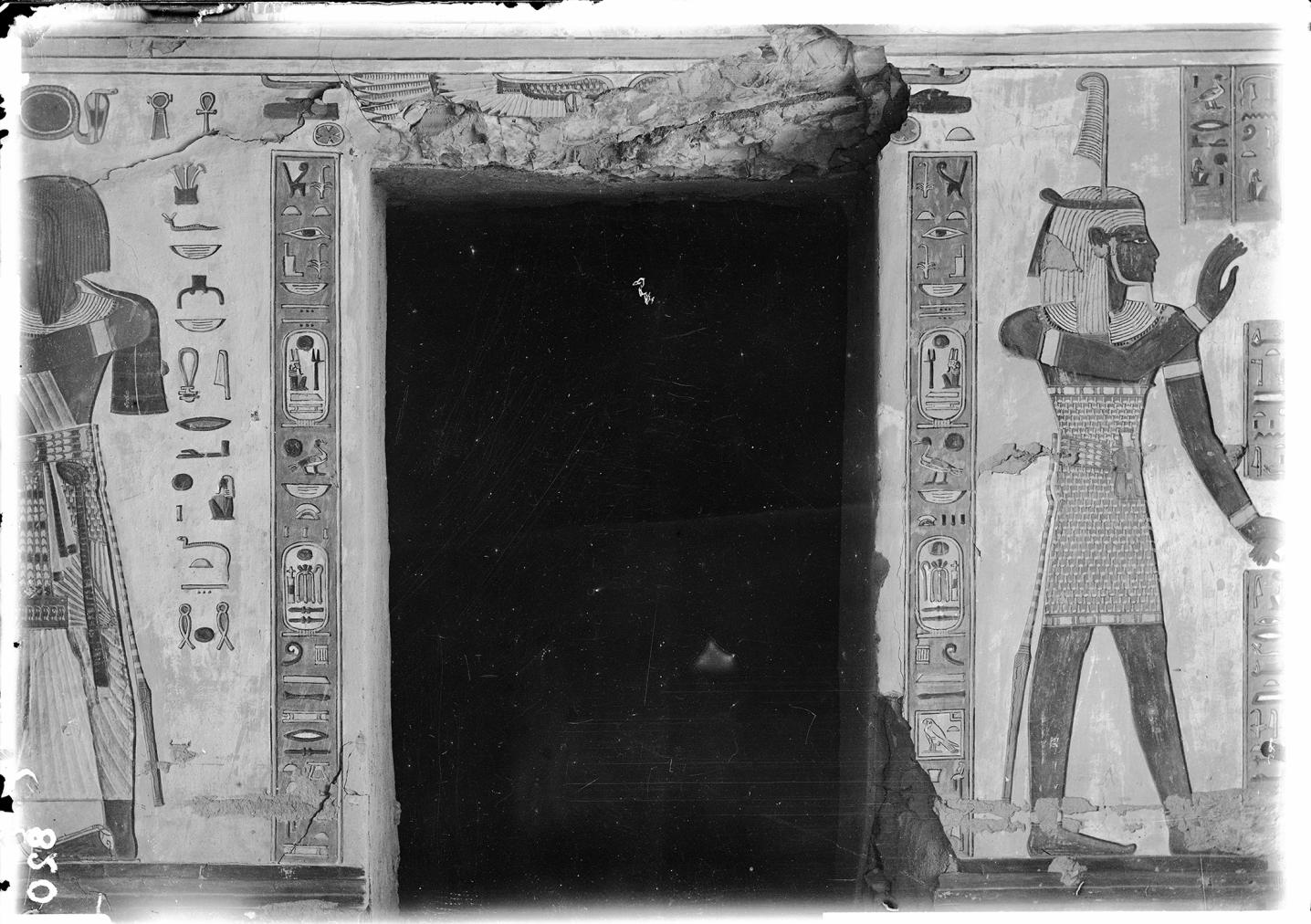

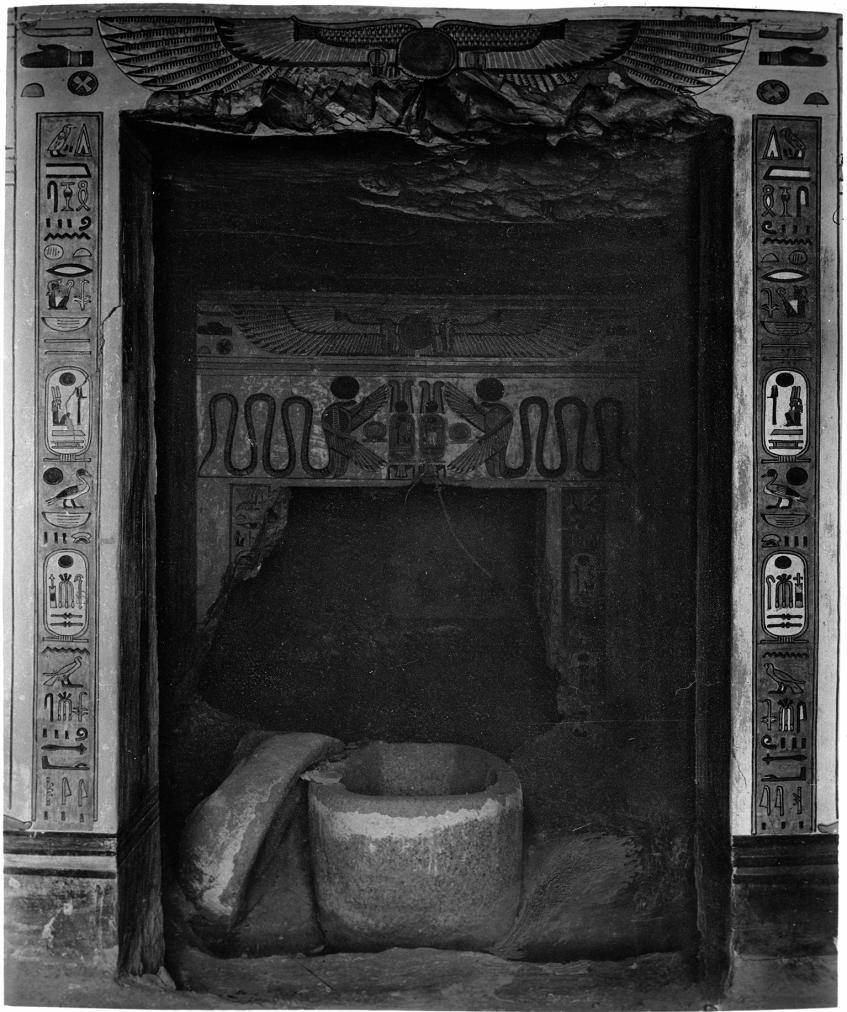

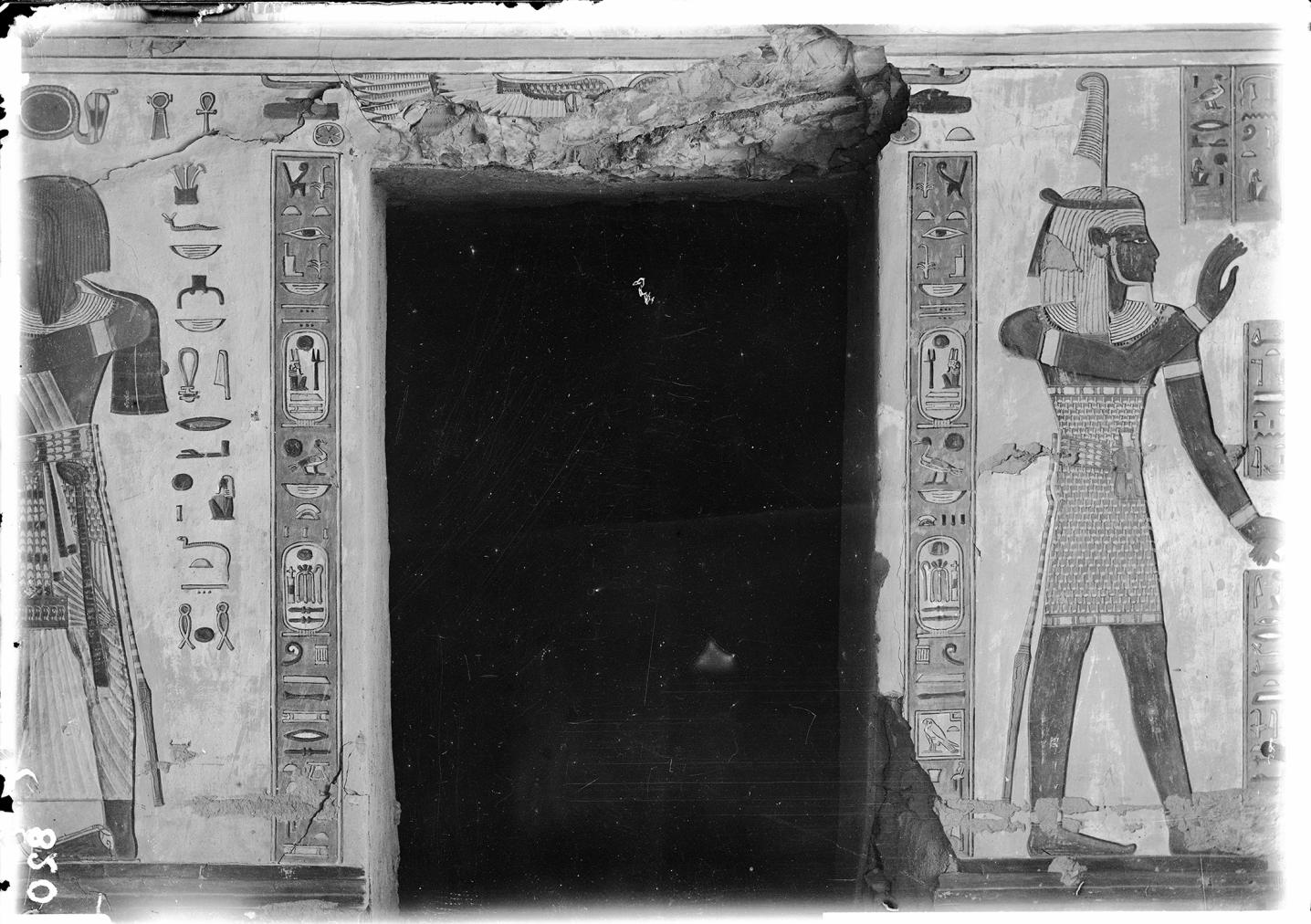

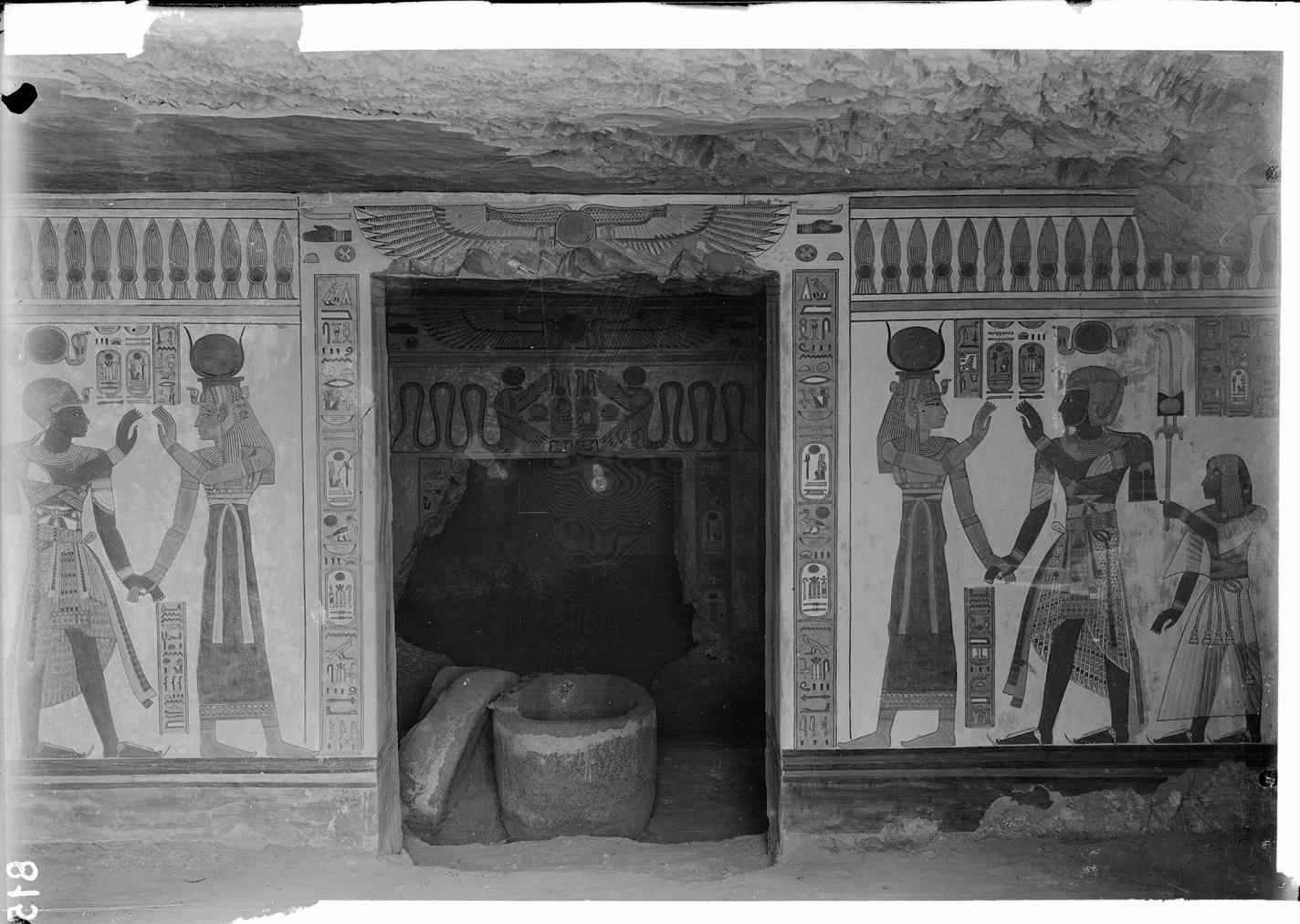

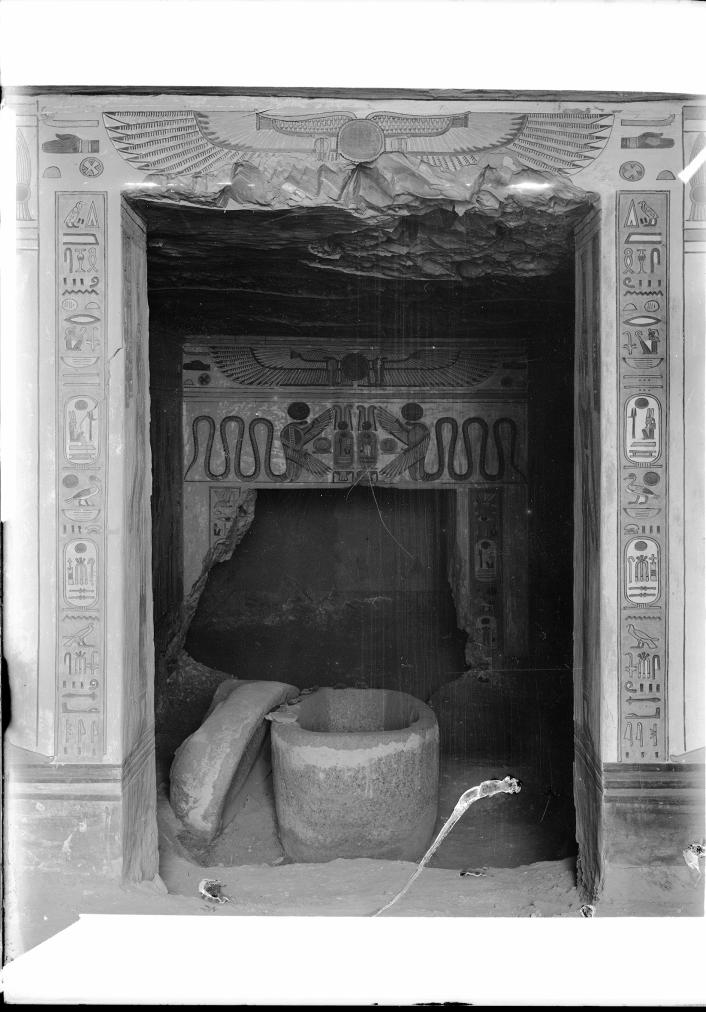

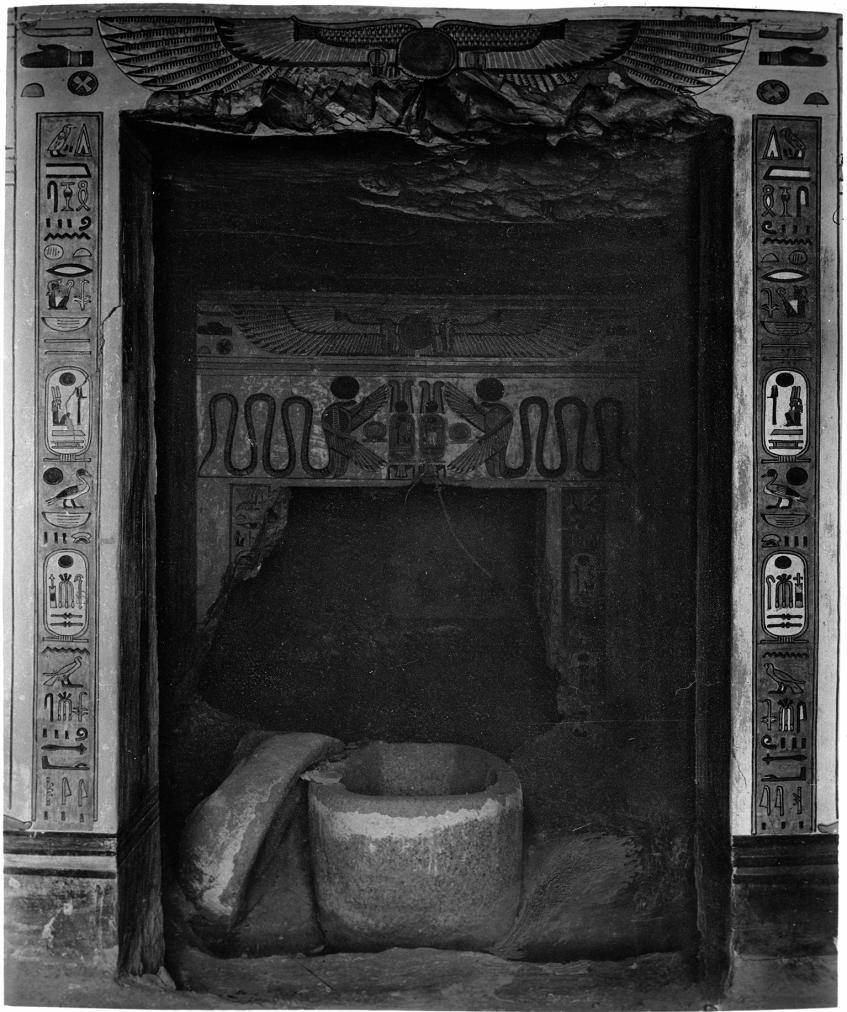

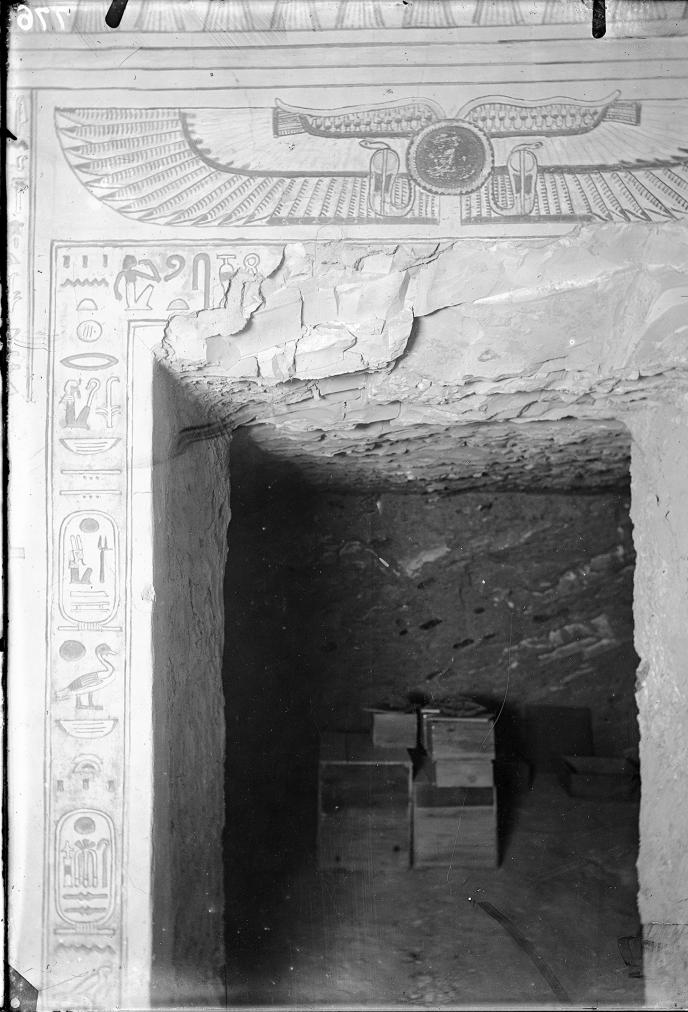

Gate C

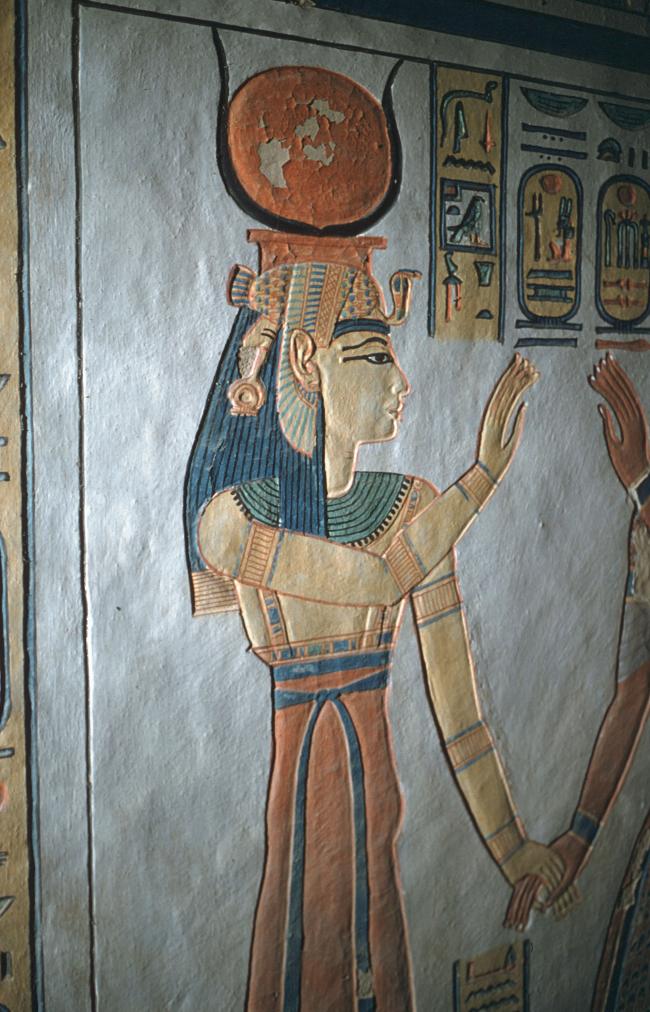

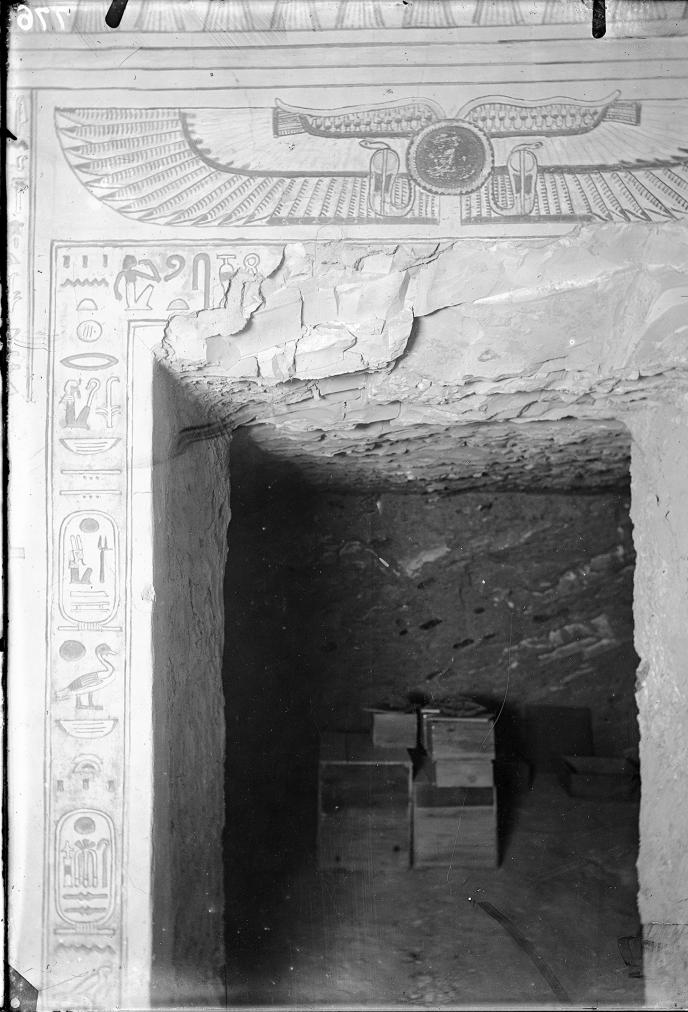

See entire tombThe outer lintel is decorated with a winged sun disk and the reveals contain the titles of Rameses III. The thicknesses have representations of Isis (left) and Nephthys (right) performing the Nini ritual.

Porter and Moss designation:

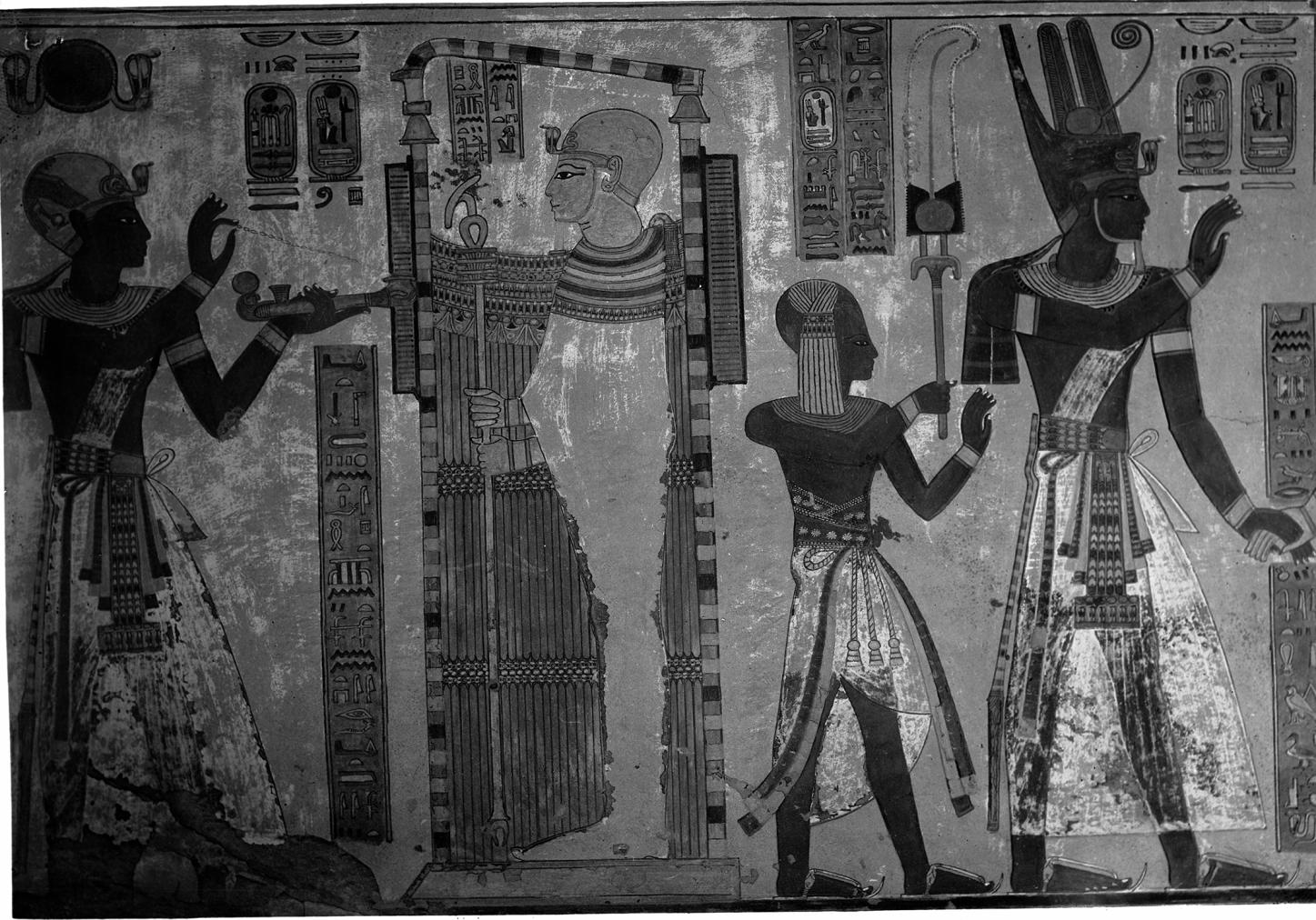

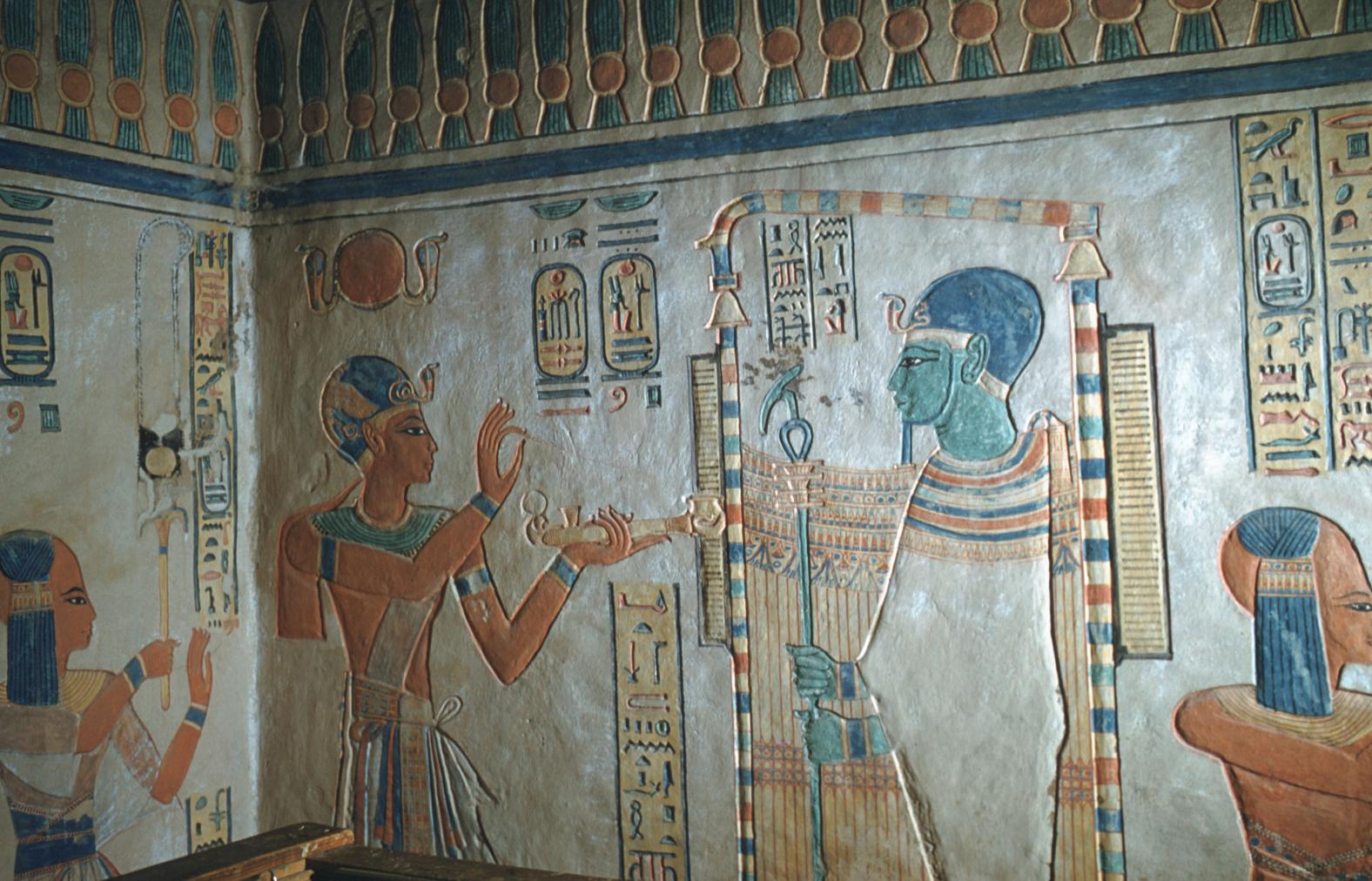

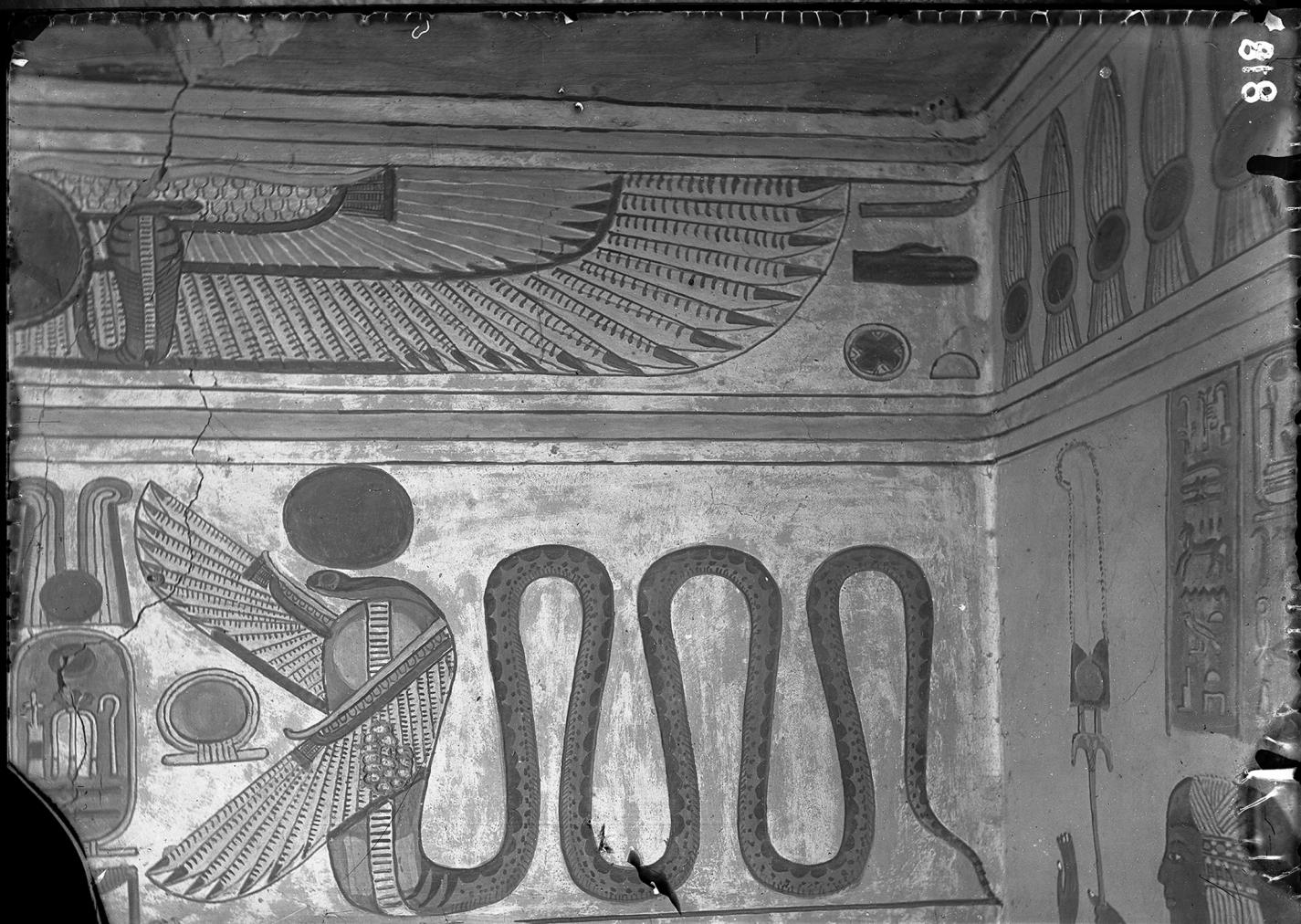

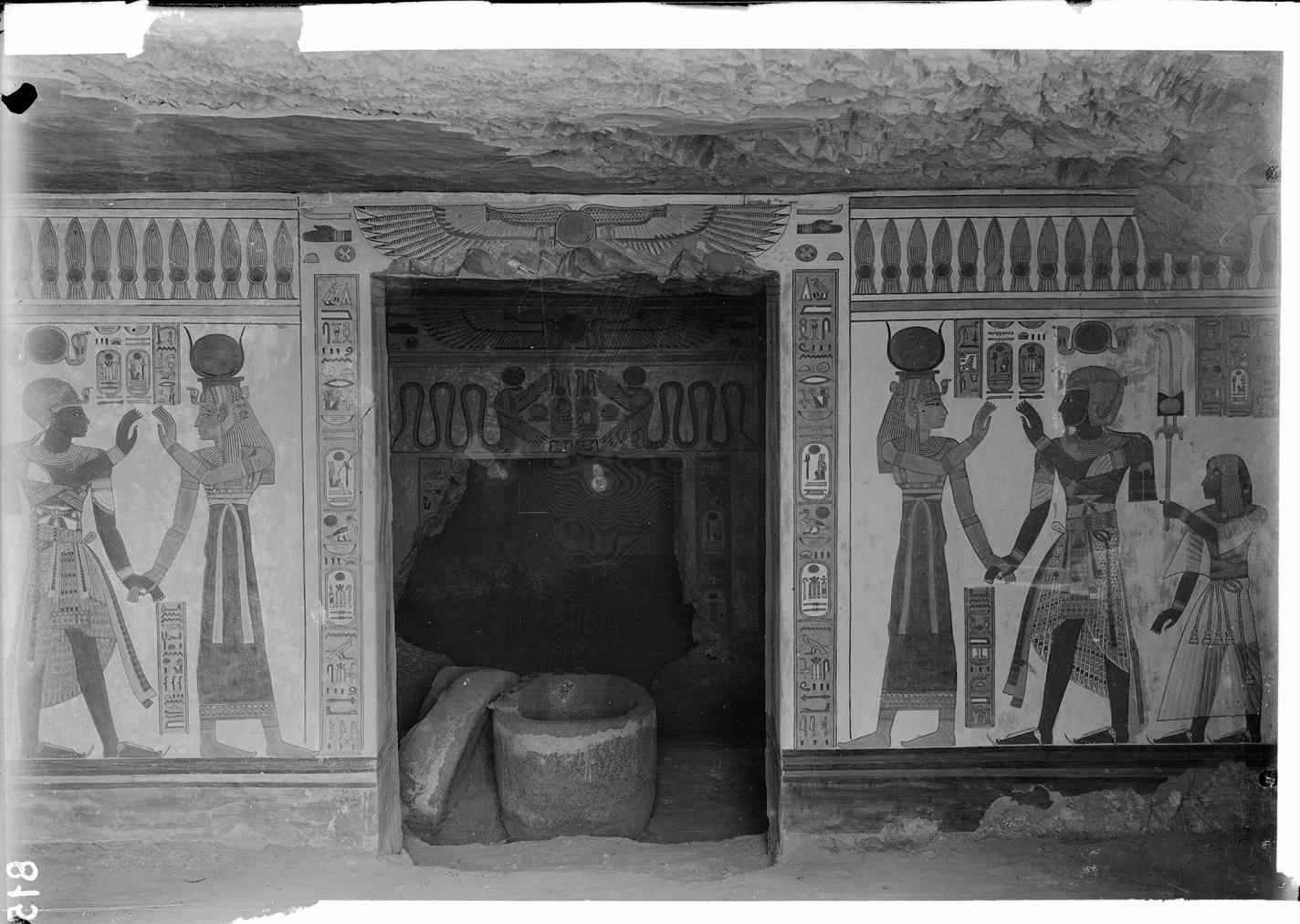

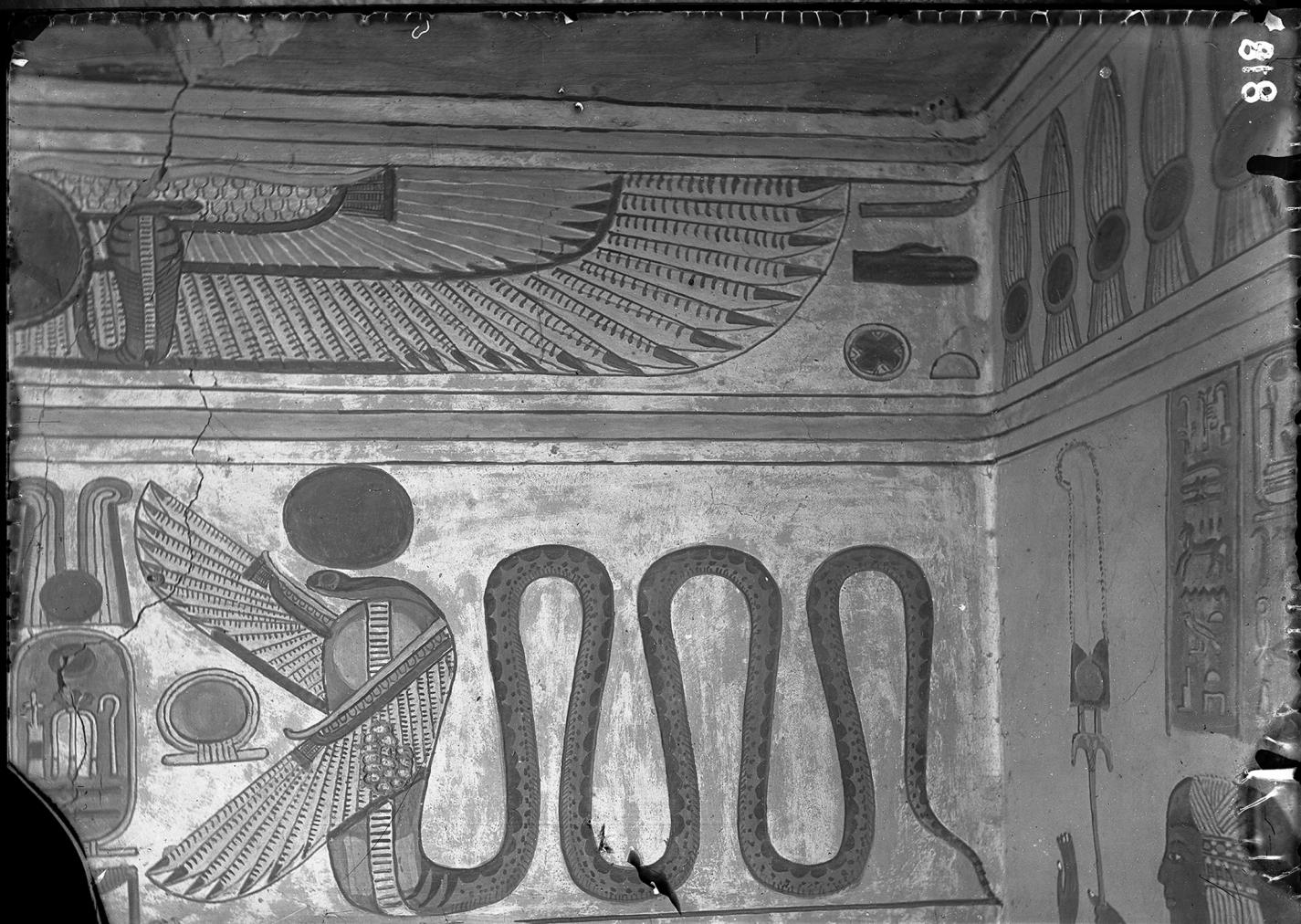

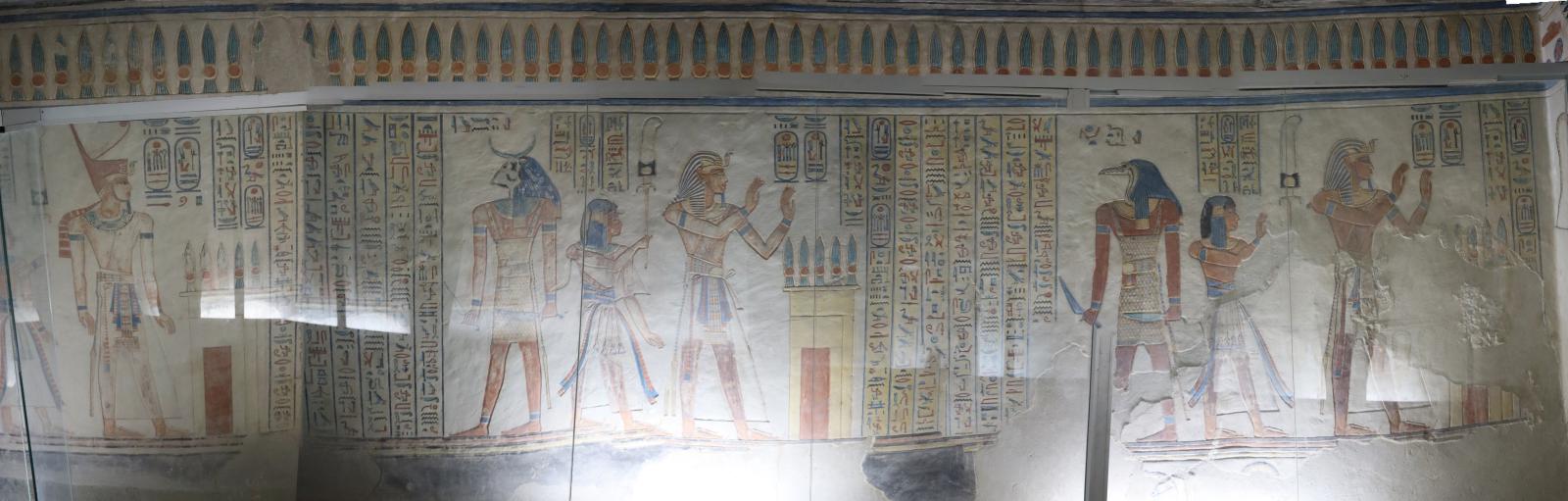

Burial chamber C

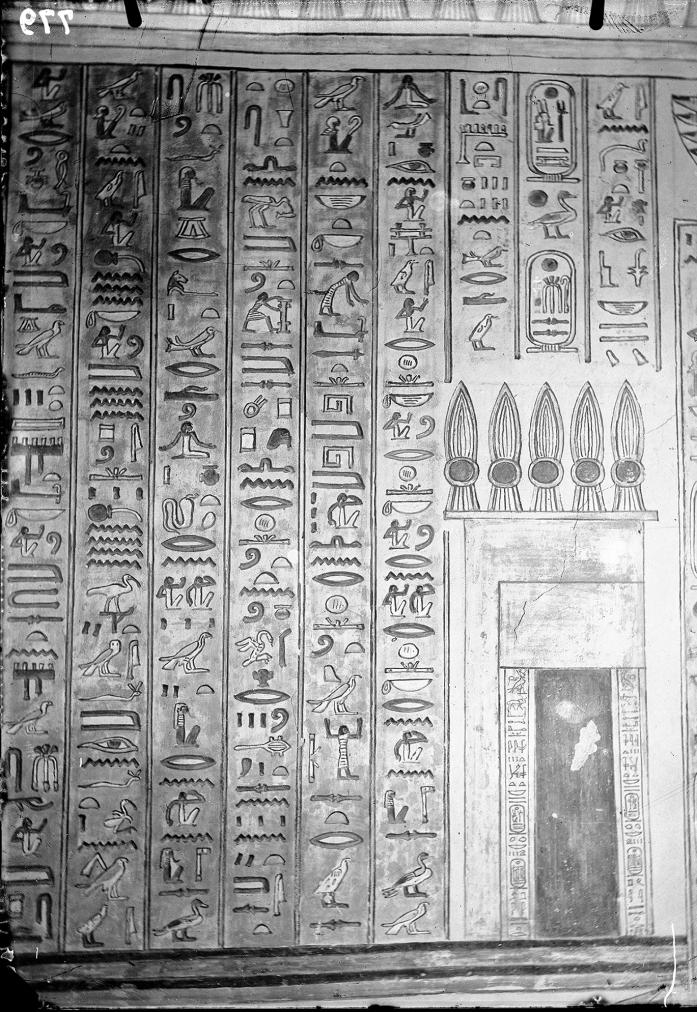

See entire tombGenerally mistaken as a corridor, chamber C in fact served as the burial chamber of QV55. The walls are decorated with four gate guardians (gates 5 to 8) from Spell 145 of the Book of the Dead. Again, the king is the dominant figure and interacts with the deities while the prince stands behind. The sarcophagus was originally found in this chamber and later moved to Chamber D.

Porter and Moss designation:

Gate Ca

See entire tombGate Ca lies in the northwest (right) wall of Burial Chamber C and leads to a side chamber. It's lintel is decorated with a winged sun disk and the reveals contain the titles of Rameses III.

Side chamber Ca

See entire tombWhile the cutting of the chamber was completed, it was not decorated.

Gate D

See entire tombThis is the last gate in the tomb. The lintel is decorated with winged ureai and the reveals contain the titles of Rameses III. The right thickness contains an unfinished representation of Nephthys, while the left is undecorated. It would presumably have contained a representation of Isis.

Porter and Moss designation:

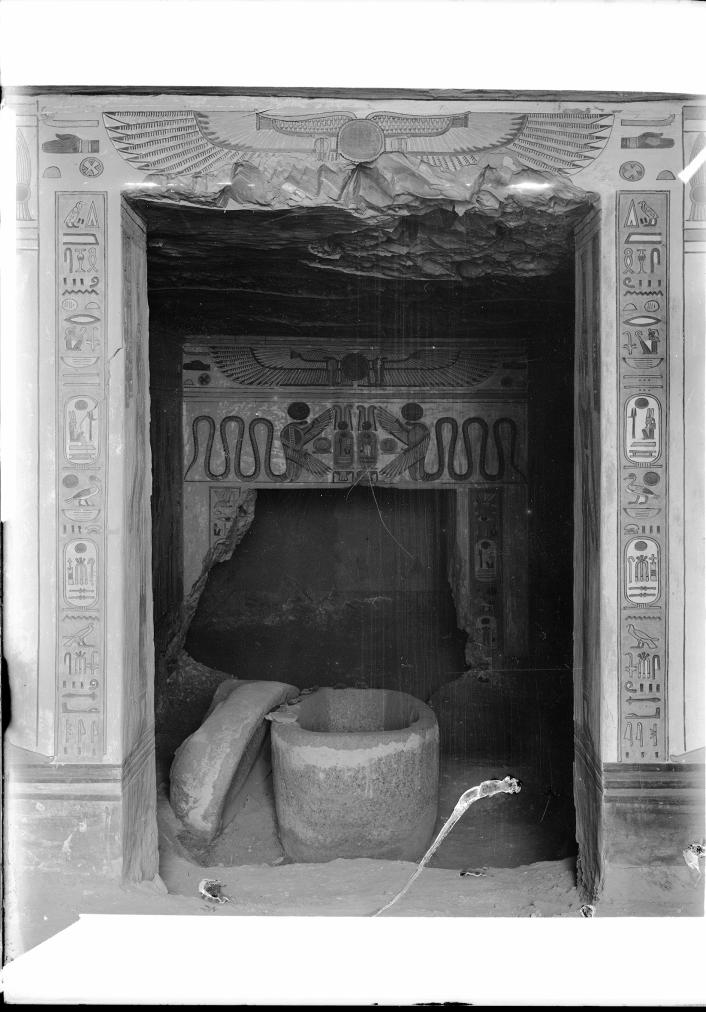

Chamber D

See entire tombThis is the last chamber in the tomb. It is undecorated. Here, the Sarcophagus, presumably meant to be used for the prince himself, is now located. However, a sarcophagus with the prince's name was found in the tomb of Bay (KV 13), usurped from Queen Tausert by Amenherkhepshef in the 19th Dynasty and later by Mentuherkhepeshef (son of Rameses VI) during the 20th Dynasty.

About

About

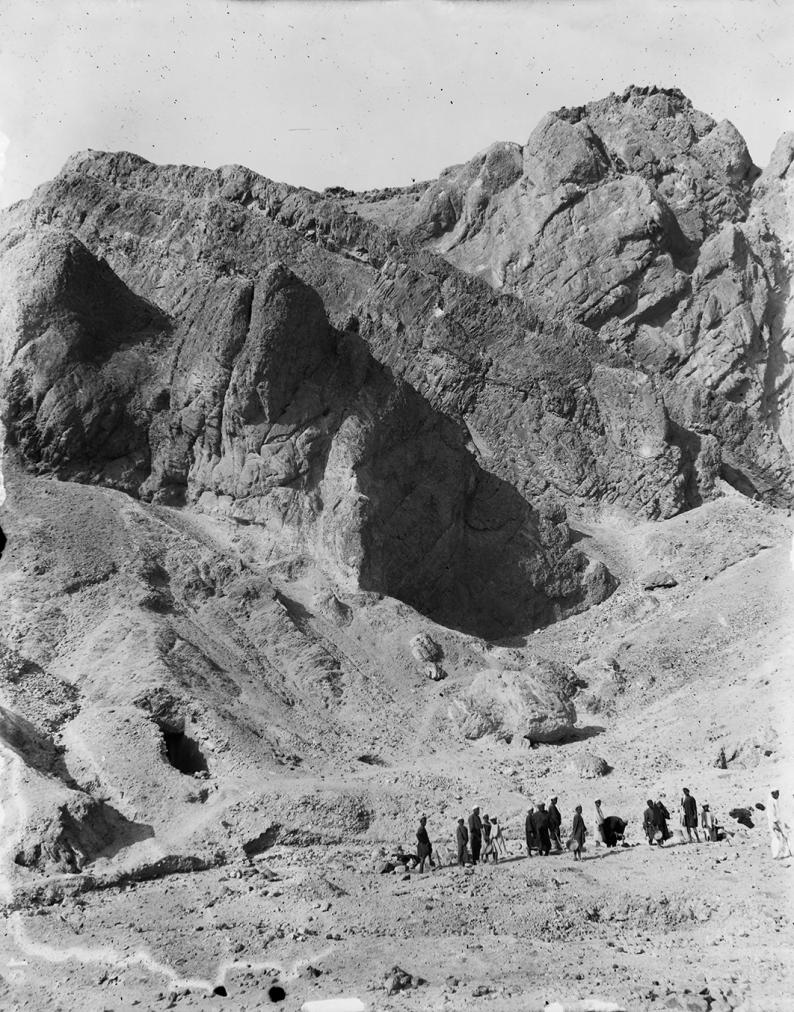

QV 55 is located at the western end of the main Wadi, and is oriented along a Northeast-Southwest axis, similar to QV 52 and QV 53. A long entry Ramp (A) leads into chamber (B) with a side chamber (Ba) to the north. Chamber (B) is followed by burial chamber (C) with side chamber (Ca) to the north and ends in a low-ceilinged rear chamber (D). This rear chamber (D) contains a granite Sarcophagus. The entry ramp has modern masonry Steps replacing the previous wooden steps. Extensive sunken relief painted plaster survives throughout the tomb. Though once evidently boldly colored, the general appearance is now abraded and the colors appear somewhat faded.

QV 55 belongs to Amenherkhepshef, the ninth on the list of sons of Rameses III at Medinet Habu. There he is given the name of Rameses-Amenherkhepshef and is listed as having died, something which probably occurred before year 30 of the reign of Rameses III. He should not be confused with his predecessor, Amenherkhepshef, son of Rameses II. He was given the titles of 'king's scribe' and 'great commander of the cavalry', as well as the more common "king's son of his body whom he loves'. Nowhere is he given the title 'king's eldest son.' Judging by the location of his tomb, it is believed that he was a son of queen Tyti, whose tomb (QV 52) is in the same area. He may not even have been buried in the QV but in KV 13, where excavations revealed a re-carved sarcophagus of Tausert with his name. A partial stelae showing his image was found at the Sanctuary to Ptah and Meretseger, probably an ex-voto by craftsmen who worked on his tomb, and a relief from Karnak and a fragment of a stela from Deir el-Medina also bear his name.

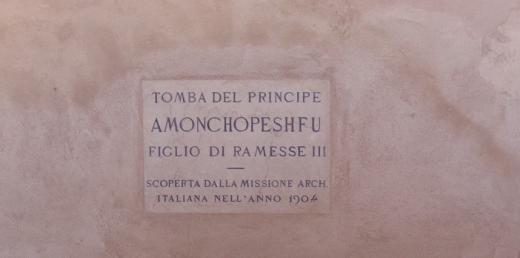

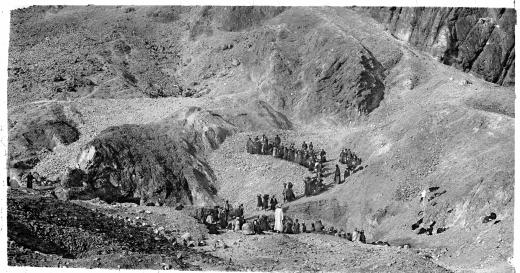

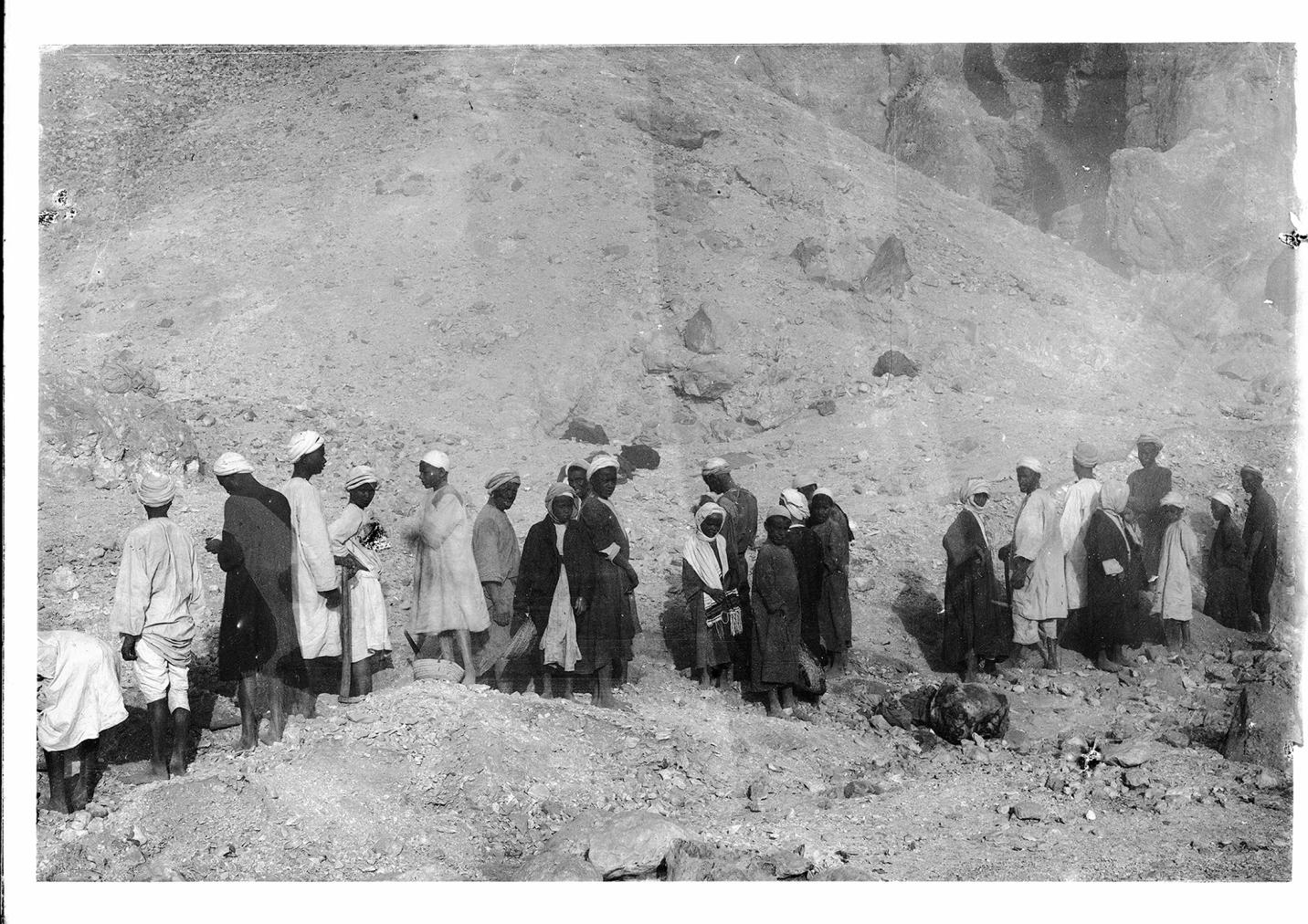

Ernesto Schiaparelli followed the trace of the ancient dam and found the upper part of the entrance ramp to the tomb in 1904. At its discovery, part of the plastered wall, which originally sealed the entrance, remained in situ. The tomb was empty except for a few funerary objects and an unfinished sarcophagus. The sarcophagus was found in corridor C, but was re-located to Chamber D to allow passage through the narrow space. The Italian mission also constructed surround walls and a vaulted cover over the entrance and installed a heavy metal door. Elizabeth Thomas (1959-60) noted that the entrance had been re-sealed with plaster after thieves had broken through, and Guy Lecuyot suggests that the tomb location was lost during the Third Intermediate Period. The Franco-Egyptian Mission carried out investigations in the tomb in 1988. Currently the tomb is open to visitation, except for side chambers (Ba) and (Ca) that are closed off. Glass barriers, fluorescent lighting, and wooden flooring have been installed. Previously, low wooden barriers were used. There are no barriers around doorway leading into the burial chamber and in chamber D.

Noteworthy features:

QV 55 is attributed to Amenherkhepshef, the ninth on the list of sons of Rameses III at Medinet Habu.

Site History

The tomb was constructed in the 20th Dynasty as recorded on an ostracon dated to Year 28 of Rameses Ill. The tomb appears to have been lost in the Third Intermediate and Graeco-Roman periods and was not reused.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

According to the GCI-SCA, the paintings have undergone extensive prior treatment, including plaster repairs and cleaning, which may have further contributed to the abraded appearance of the surface. There is also evidence of injection grouting and surface consolidation seen in the large number of stains and drips running down the paintings. Ceiling areas have been the focus of repeat treatments, most recently in 2009-2010 and prior to this in 2005, in response to cracking in repair plaster. The repeat treatments suggest that the method and materials of treatment may not have been effective in solving the problem and that the problem itself may not be fully understood. The Ramp wall repair plaster on the south side is heavily cracked and detached in some areas. The SCA undertook treatment of the wall paintings and installed new infrastructure in chamber (D) in February 2010.

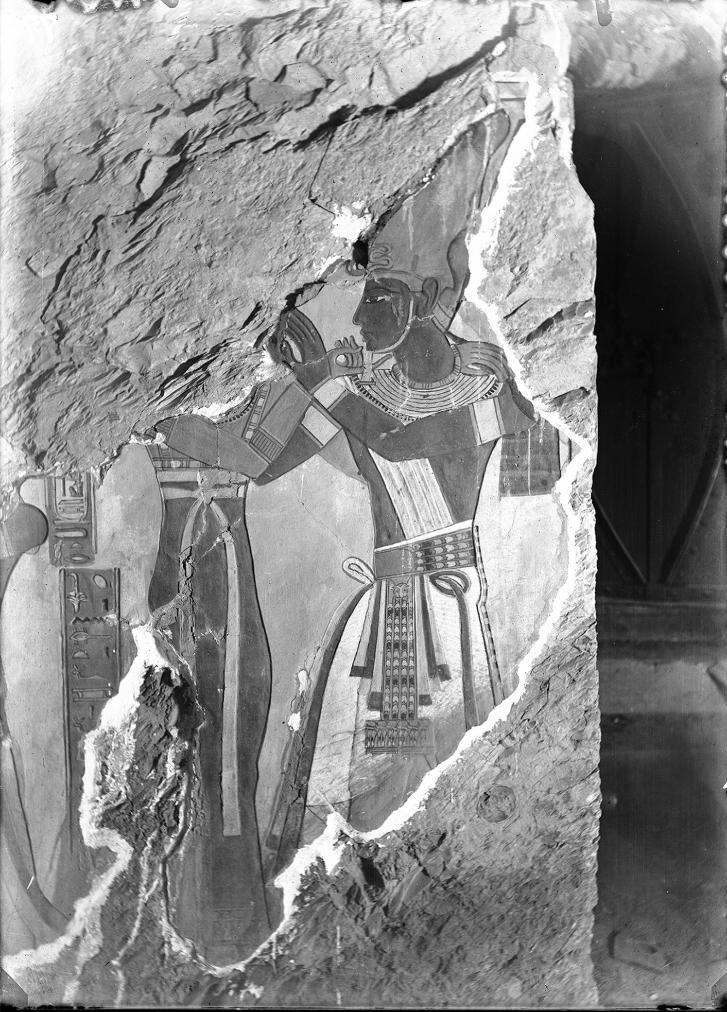

Site Condition

The late discovery of the tomb by Ernesto Schiaparelli explains its generally good condition as it was essentially sealed until the early 20th century. According to the GCI-SCA, the ceilings have suffered substantial losses and historic photographs before their repair show loss occurring along fractures in the heavily jointed rock. A few of these fractures, such as the one that appears on Gate D, extend from the ceiling down the wall. However, at present, the cracks do not appear to be endangering. The few small areas of visible ceiling rock appear to be in good condition. The rock in side chamber (Ba) is heavily jointed and irregular, but there is no sign of recent loss. There is excellent survival of the decoration in this tomb, but there are also large losses, mainly in the ceilings, that have been filled with a modern repair plaster. These plaster fills are slightly recessed from the level of the original painted plaster. There appear to be at least two different major campaigns of plaster repairs in the tomb. Some of these repairs are now cracking, especially in chamber (B), and some loss of this repair plaster from cracks in the ceiling may suggest movement and possible rock instability underneath. However, at present, there is not enough evidence to conclusively determine whether or not cracks indicate real instability or just a failure of the repair plasters themselves. Areas of the decoration that are unprotected by glass barriers are stained brown from the hands of visitors, such as the jambs of doorways at the entrance and gate D. The painted surfaces show preferential loss of areas - namely the blue pigment, as well as the white background, which in some areas are almost completely gone. Overall the painted surfaces also have an abraded appearance with pigment loss. There is evidence of past bat activity. Although the tomb opening is located in a low lying position adjacent to the main Wadi, Christian Leblanc has noted that water did not enter the tomb during the flood in 1994 because the entrance was blocked with sand bags. The survival of painting on the walls to the floor in many areas of the tomb indicate that, if the tomb previously flooded, related damage was minimal.

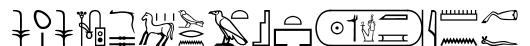

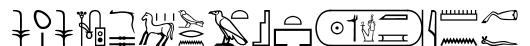

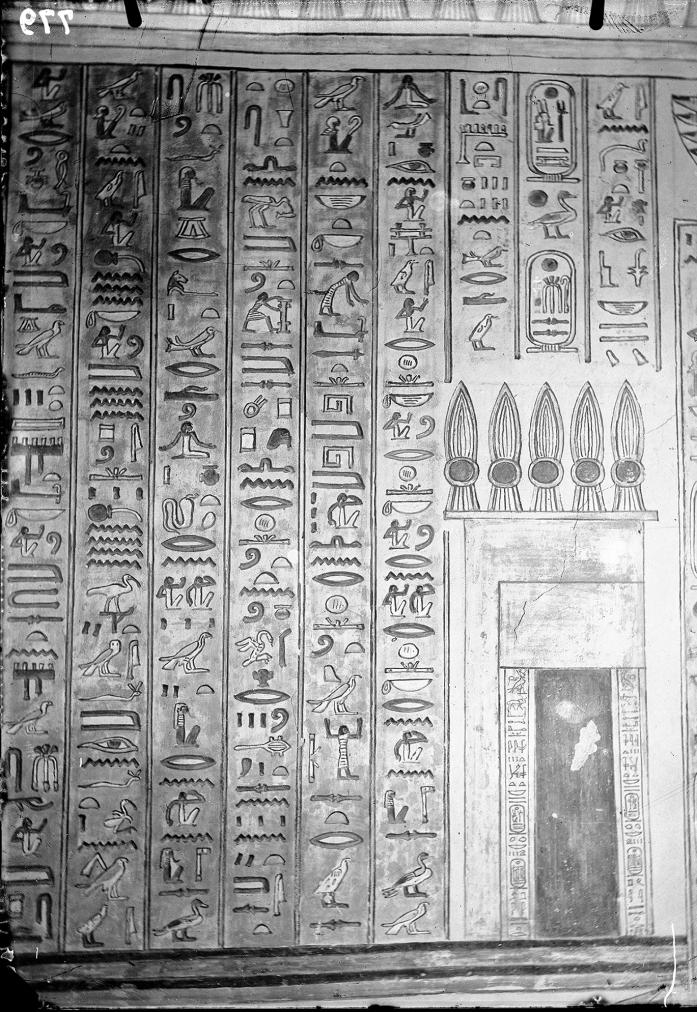

Hieroglyphs

Prince Amenherkhepshef

King's Son, Royal Scribe, Great Overseer of Horses of the Place of Ramesses III, Amen(her)khepshef

sA-nswt sS-nswt imy-r ssmt wr n tA st wsr-mAat-ra, imn-(Hr)-xpS.f

King's Son, Royal Scribe, Great Overseer of Horses of the Place of Ramesses III, Amen(her)khepshef

sA-nswt sS-nswt imy-r ssmt wr n tA st wsr-mAat-ra, imn-(Hr)-xpS.f

Articles

Tomb Numbering Systems in the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis

Geography and Geology of the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis

The Italian Mission in the Valley of the Queens (1903-1905): History of excavation, Discoveries, and the Turin Museum Collection

Bibliography

Abitz, Friedrich. Ramses III. in den Gräbern seiner Söhne (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 72). Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätverlag and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986.

Bruyère, Bernard. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el Medineh (1924-1925). Fouilles de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire 3, 3 (1926). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire.

Campbell, Colin. Two Theban Princes: Kha-em-Uast and Amen-Khepeshef, Sons of Rameses III, Menna, a Land-Steward, and Their Tombs. London: Oliver and Boyd, 1910.

Demas, Martha and Neville Agnew (eds). Valley of the Queens. Assessment Report. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2012, 2016. Two vols.

Dodson, Aidan and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Gosselin, Luc. Les divines épouses d'Amon dans l'Egypte de la XIXème à la XXIème dynastie. Etudes et mémoires d'égyptologie, no. 6. Paris: Cybèle, 2007.

Grist, Jehon. The Identity of the Ramesside Queen Tyti. Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

Grist, Jehon. The Identity of the Ramesside Queen Tyti. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 71 (1985): 71-81.

Hassanein, Fathy and Monique Nelson. La tombe du prince Amon-(her)-khepchef. Cairo: Centre d’études et de documentation sur l’ancienne Egypte, 1976.