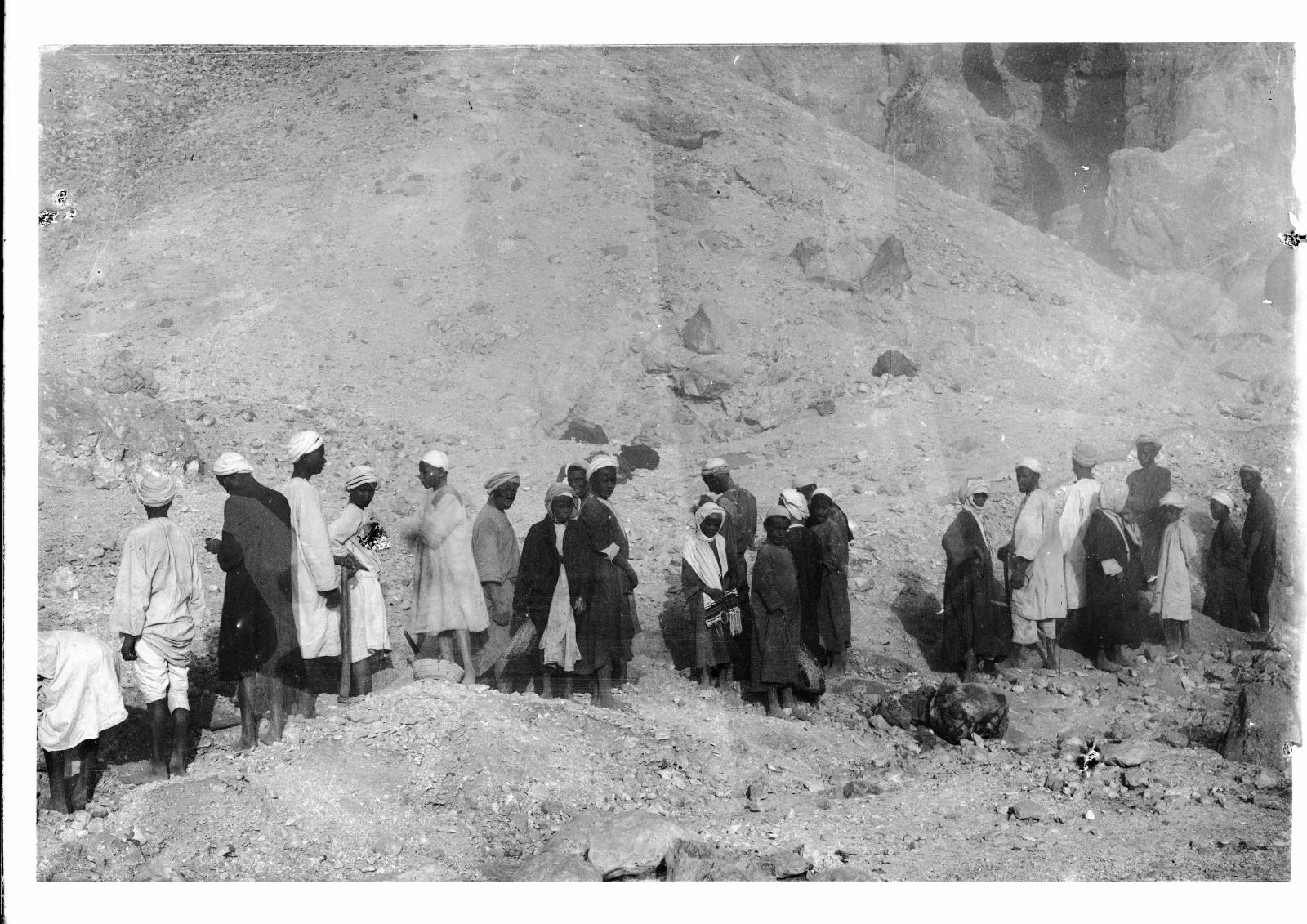

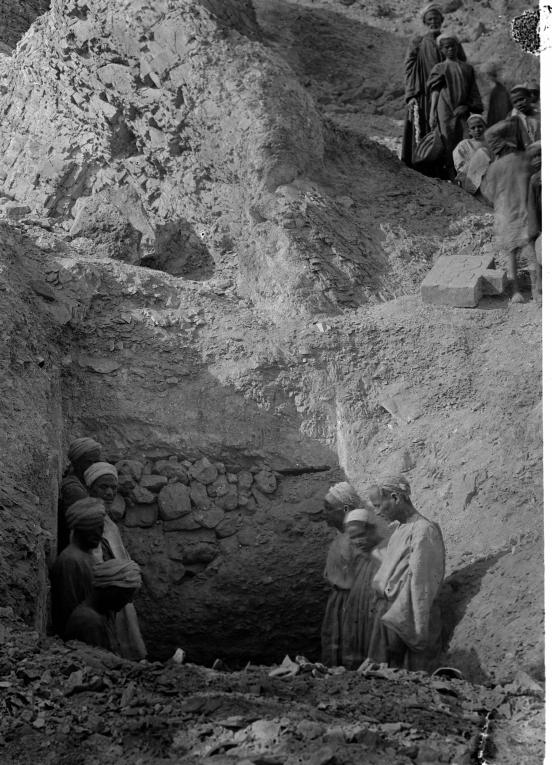

In early 1903, an Italian Mission from the Turin Museum was granted a concession to excavate in the Valley of the Queens and subsidiary wadis. The mission was headed by two Italian Egyptologists, Ernesto Schiaparelli (1856-1928) and Francesco Ballerini (1877-1910). Schiaparelli had been the director of the Egyptian section of the Florence Museum from 1880-94 and was appointed director of the Turin Museum in 1894. Ballerini joined the staff of the Turin Museum in 1902 and assisted Schiaparelli in his excavations until 1910. In the winter of 1903, Schiaparelli and Ballerini began a systematic exploration of the valley, clearing large masses of debris to reach the ancient soil level. Their work, which ran until 1905, began in the eastern and southern sections of the main valley, continued into the western section and Valley of Prince Ahmose, headed towards the center, and finally culminated at the northern end.

By the time the Italian mission began their excavations, the Valley of the Queens had already been looted and changed considerably. Schiaparelli notes in his report of the excavations – “like every other part of the Theban necropolis, [the valley has been] in every part tampered with and looted…during a period of more than thirty centuries, i.e. beginning with contemporary Egyptian period of the tombs excavated in the same valley, descending to the Christian period - in which numerous nuclei of Copts had settled there…had built a convent, of which also presently there are considerable ruins — coming from the Arab period up to a few decades ago.” (Schiaparelli, 1923: 7) Schiaparelli was also aware that numerous Egyptologists had visited the valley and studied the accessible tombs of that time (such as QV 51, QV 52, and QV 60), but noted that no scientific mission had so far undertaken a systematic exploration.

The work of the Italian mission led to a number of significant discoveries. Apart from several anonymous tombs, Schiaparelli and Ballerini also uncovered the tombs of Princess Ahmose (QV 47), Prince Ahmose (QV 88), Imhotep (QV 46), Nebiry (QV 30), the famous Queen Nefertari (QV 66), as well as the sons of Rameses III - Princes Khaemwaset (QV 44), Setherkhepeshef (QV 43), Amenherkhepeshef (QV 55), and Pareherunemef (QV 42). These tombs held a varied assortment of finds – including but not limited to a Book of the Dead Papyrus belonging to Princess Ahmose; stone sarcophagi belonging to Prince Khaemwaset and Queen Nefertari, as well as several coffins from the Third Intermediate and Late Periods; scarabs, amulets, beaded funerary nets, and shabtis; pottery and baskets; and mummified meat offerings (beef and ducks).

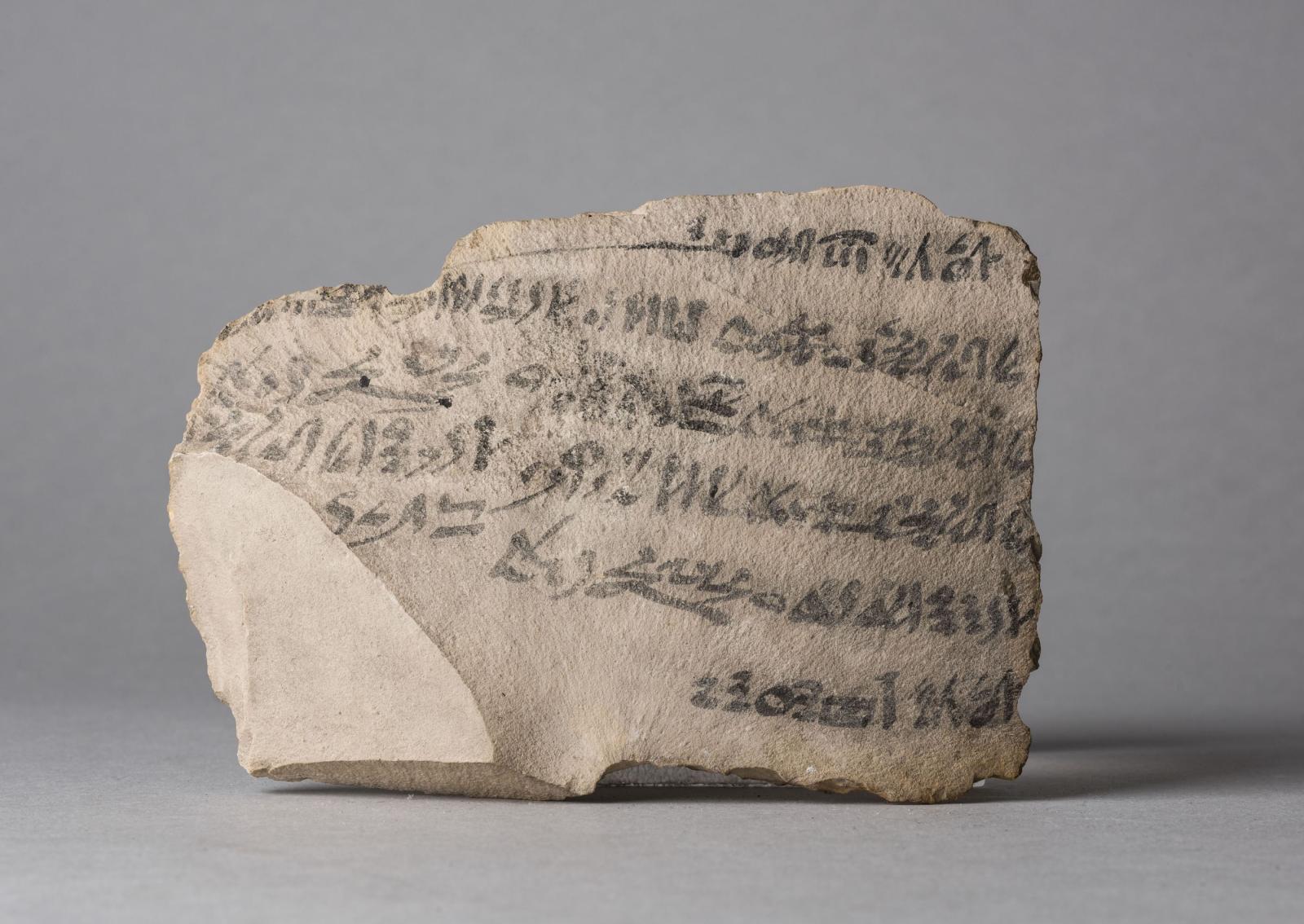

Apart from the contents of the discovered tombs, the Italian mission also found a large collection of Ostraca within the valley. These ostraca are of significance to our understanding of tomb construction, administration, and the daily lives of tomb workers, as they detail accounts, events, and the attendance record and names of hired individuals. Several of them also bear preliminary sketches for the tombs by the tomb artists, as well as figurative drawings. According to Schiaparelli, the importance of these ostraca lay not only in their contents, but also in their discovered location.

“It is necessary to take into account, to clarify the reason why the ostraca - whatever its character - are usually found grouped in relatively circumscribed areas, so that the excavation sometimes proceed for whole weeks without finding even a single ostracon, and then in a few hours, tens are found…this is precisely because the excavation has approached a point of the necropolis in which some overseer had fixed his resting place…that the discovery of an area rich in ostraca can also indicate the proximity of one tomb that is not yet known." (Schiaparelli, 1923: 165-166).

Large groupings of ostraca were thus usually discovered in close proximity to tomb entrances and proved useful in uncovering unknown tombs, such as that of the sons of Rameses III (Khaemwaset, Setherkhepshef, and Pareherunemef).

The finds from the Italian Mission’s work in the Valley of the Queens and Valley of Prince Ahmose were transported to the Turin Museum in Italy shortly after the mission's end and are now on display as part of the museum’s vast Egyptian collection. To view these objects and learn more, click here. The numerous photographs taken during the excavations have also been digitized, reorganized, and studied by the Turin Museum’s Photographic archive team, and have been made available online here. We wish to thank the Turin Museum for not only making their collection more readily available to the general public, but also for their generosity in allowing ARCE to reproduce their photographs on the TMP website!

References:

Bierbier, Morris L. (Ed.). Who was who in Egyptology. 4th Edition. London: The Egyptian Exploration Society, 2012.

Schiaparelli, Ernesto. Realazione sui lavon della Missione archeologica italiana in Egitto, anni 1903-1920. I: Explorazione della ”Valle delle Regina” nella necropolis di Tebe. Turin, 1923.