The royal tombs cut in the Valley of the Kings during the New Kingdom represented a shift in form and location from the royal cemeteries that preceded them. As Egyptian society gradually developed from the predynastic chiefdoms to the first united kingdoms of the Early Dynastic Period (Dynasty 1 and Dynasty 2), impressive royal tomb complexes were constructed, surrounded by cemeteries of courtiers and servants.

The characteristic tomb of the Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom was a rectangular flat-topped superstructure with steep sloping sides called a mastaba (after the Arabic word for the benches found in front of village houses). In fact, the origin of this superstructure can be traced back to prehistoric times when mud brick and rubble mounds covered pit graves. These soon developed into more regular and elaborate forms that eventually included an offering chapel—a small chamber--built into the Mastaba. The focus of the offering ritual was a "false door," a recessed panel, usually in the west wall, that represented the symbolic interface between the physical realm of the living and the spirit realm of the dead.

It was from the mastaba form that pyramids, the quintessential symbol of ancient Egyptian culture, developed. Many argue that the pyramid shape also symbolized the primeval hill that emerged from the waters of chaos in which the creator-god brought forth all life. Others see the pyramid as a material manifestation of the rays of the sun, sources of light and life. Certainly, as a potent symbol associated with creation, the pyramid served to initiate the forces of resurrection of the human remains lying beneath it.

In addition to the pyramid itself, the Old Kingdom royal mortuary complex included two separated sites for the ritual activities of the mortuary cult. Close to the east side of the pyramid stood a mortuary temple in which regular presentations of offerings were made for the spirit of the dead king. From here, a causeway led down to a "Valley temple" near the edge of the cultivation and the Nile where funerary rites concerned with purification and preparations for burial were carried out. Smaller satellite pyramids, usually for queens and princesses, together with mastabas for other members of the royal family and court officials, surrounded the king's complex.

Theban Necropolis (Middle Kingdom & Second Intermediate Period)

During Dynasty 11, a series of Theban princes named Intef initiated the process of the political reunification of Egypt. The importance of the Theban region greatly increased during this period. These princes were buried in complexes cut into low gravel hills at Tarif, at the northern end of the Theban Necropolis. Called saff tombs (saff meaning "row" in Arabic), the complexes were fronted by a long rectangular courtyard and a western portico consisting of one or two rows of pillars behind which lay rock-cut offering chambers and burial crypts. Some think these saff tombs had pyramidal superstructures, but no traces of these survive.

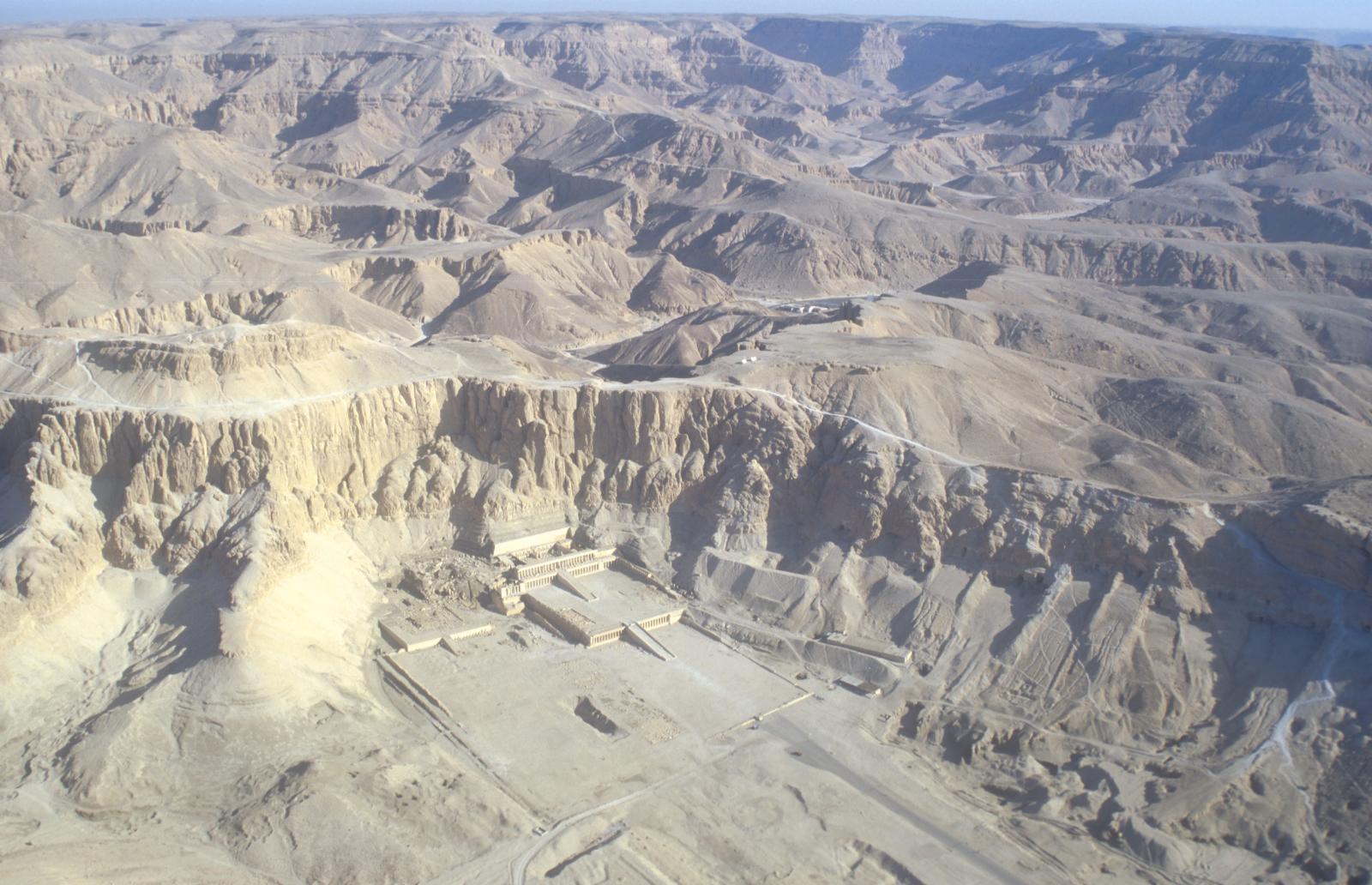

The paradigm of Old Kingdom royal tombs and those of attendant family members and courtiers continued in a somewhat altered form after the First Intermediate Period, into the Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11 and Dynasty 12). The king who brought the reunification to completion, Mentuhetep II, had a monumental platform constructed in front of the cliff face in the Dayr al Bahri Cirque.

Although the royal residence and its necropolis was moved to the area between the Fayyum and Memphis in Dynasty 12, the important officials of Thebes continued to construct their tombs in ancestral cemeteries on the Theban West Bank, particularly around the mortuary complex of Mentuhetep at Dayr al Bahri. As in many other necropoli of this time (such as those at Aswan, Bani Hasan, Barsha', Qaw al Kabir, and Meir), the elite tombs tended to be cut in the slopes of the cliffs and hillsides. They featured prominent ascending approach ramps, courtyards, and facades leading to decorated offering chambers and burial shafts.

During Dynasty 17, at the end of the Second Intermediate Period, a Theban princely family was buried in the traditional necropolis at Dira' Abu al Naga. Most of the tombs of these rulers have not been Identified, although their existence and general location is known from Papyrus Abbott, which described Dynasty 20 investigations of tomb robberies. The tombs were said to have a pyramid, probably of mud brick, atop their superstructure. During excavations in the area, Daniel Polz of the German Archaeological Institute identified one of these tombs as that of Intef VII.